Growing up in a Black household, Tyeranee Scott was taught that if she was ever stopped and questioned by police, she needed to put her hands on the steering wheel, make eye contact with the officer and have her license and registration ready to go.

“[My mother taught me that if] I were to get pulled over and then my white friend were to get pulled over, it would just be different,” Scott said. “Every time I get pulled over, my mom always wants me to call her so she can hear everything that’s going on.”

Scott, a Texas State volleyball senior, is one of the countless Black students and athletes taught by parents how to conduct themselves when law enforcement is present, an indication of the plight Black families face when trying to keep their loved ones from becoming mere statistics.

With summer practices on hold and the centuries-long fight for Black lives ongoing, Black Texas State athletes have had more time than usual to reflect on the lessons their parents taught them growing up, the Black Lives Matter movement and their experiences as Black athletes.

For Scott, who participated in a protest for the late George Floyd in her hometown of Houston, the demonstration felt personal. Scott said witnessing Floyd’s family speak in person was surreal because she knows that any of her Black friends or family members could have also been victims of police brutality.

“Even though I don’t directly know George Floyd and his family, it feels like I do because he’s the same color as me, and I know that those injustices could happen to anybody just because of their skin color,” Scott said.

Throughout her career, Scott says she has experienced racist and insensitive remarks from coaches and teammates on more than one occasion. Scott says the situations made her uncomfortable, but her teammates showed constant support throughout them.

“My teammates would come in and say, ‘that sounded racist,’ and pull me to the side and basically say that [even though they aren’t people] of color, they’re still here with me,” Scott said. “I’m very appreciative of the people who talk to me outside of it and see my problem as their problems too.”

Sophomore track athlete Ariana Ealy-Pulido, a Black and Latina woman, has had a different experience. Ealy-Pulido said she did not become aware of police brutality and racial discrimination until college.

“If I have [experienced discrimination], I was probably oblivious to it or wasn’t able to define it at the time,” Ealy-Pulido said. “Growing up, police brutality wasn’t really a concern for me or my loved ones, and I didn’t become aware until I was much older. When I got to college, that’s when I realized that this is a real issue.”

Now that Ealy-Pulido is aware, she says she is unhappy with how the police have been handling the ongoing Black Lives Matter protests, especially their use of tear gas, rubber bullets and other sometimes-lethal weapons on unarmed citizens.

“For the most part, I think that the police want to protect the community, but some are also handling these protests the wrong way,” Ealy-Pulido said. “For instance, with the tear gas and rubber bullets that are being used during the protests, that can cause a disproportionate use of force that can easily turn a peaceful protest into a violent one, and that’s when things get chaotic.”

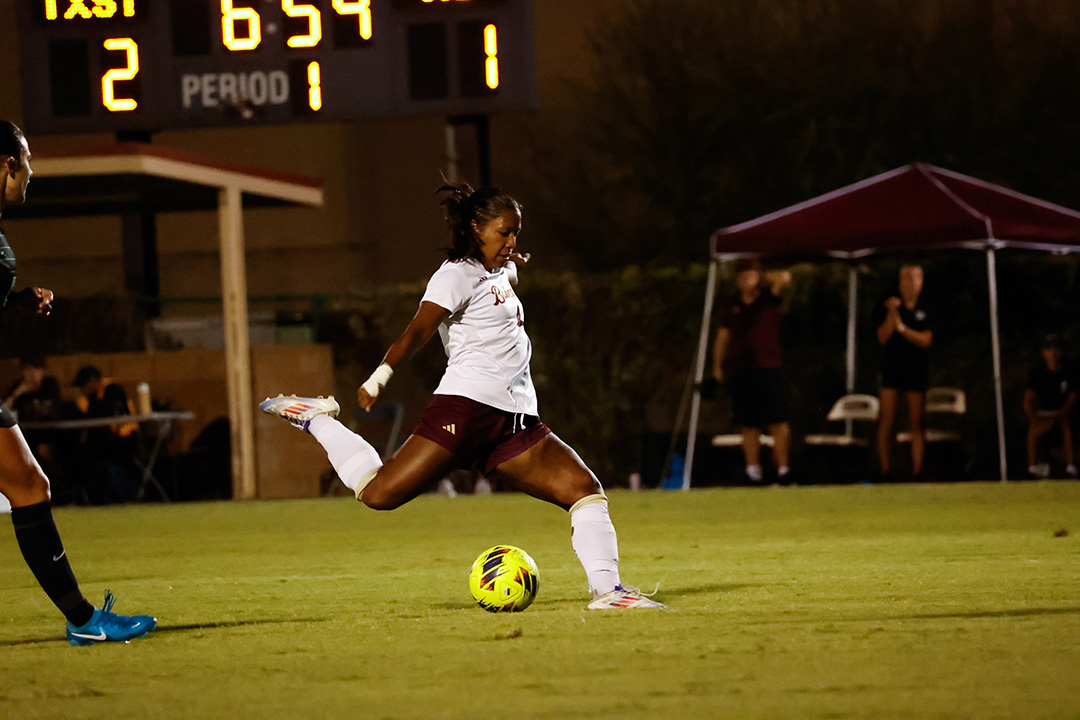

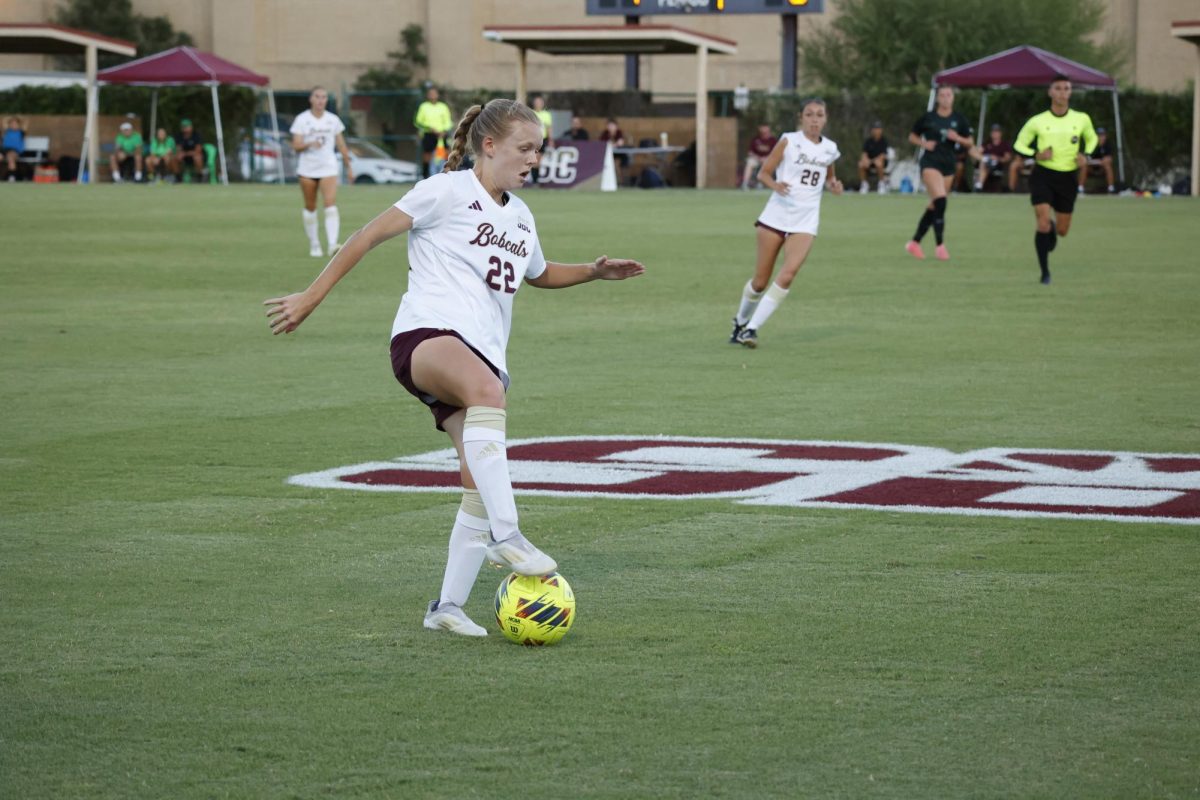

Kiara Gonzales, a soccer sophomore, has played on predominantly white teams throughout her life. She says she cherishes the opportunity to be able to play at Texas State alongside other Black athletes who look like her and understand her as a person—especially during such an emotional time for Black people.

“I never had that type of experience [of having Black teammates],” Gonzales said. “I was always one of the only Black people on the team, so it’s been really fun just to play with other athletes that are Black and become really good friends with them.”

A more diverse team has provided Black athletes with a much-needed support system and white team members the opportunity to become educated on racial injustice, according to Kamaria Williams, Gonzales’ teammate.

“A lot of the girls on our team really didn’t know a lot about Black people, so having us on their team allowed them to open their eyes and have those conversations that they may be questioning,” Williams said. “I think that we’ve made an impact on the team, and I think we also influence each other to be more like ourselves and love our skin because we can support each other during that process.”

Black athletes are also using their social media platforms during times like these to reach more people about important racial issues, but Scott says doing so can be more limiting than liberating.

“I feel like I have to maybe sugarcoat how I really feel,” Scott said. “So even though I’m still speaking out against police brutality, I can’t say a lot because I am [an] athlete, because I don’t want to cross those boundaries and step on any toes.”

Despite feeling restricted at times, for Ealy-Pulido, having a platform motivates her to not only speak out but also act against racial injustice.

“Athletes can use their platform for good or bad, but I choose to use mine in a positive way, to be a light and introduce change from signing petitions to donating or supporting minority businesses,” Ealy-Pulido said.

Categories:

Athletes voice their support for the Black Lives Matter movement

July 8, 2020

Tyeranee Scott (left) and her friend Cameron Flores (right) attended a protest in Houston, Texas in which the family of George Floyd spoke to the crowd.

0

Donate to The University Star

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover