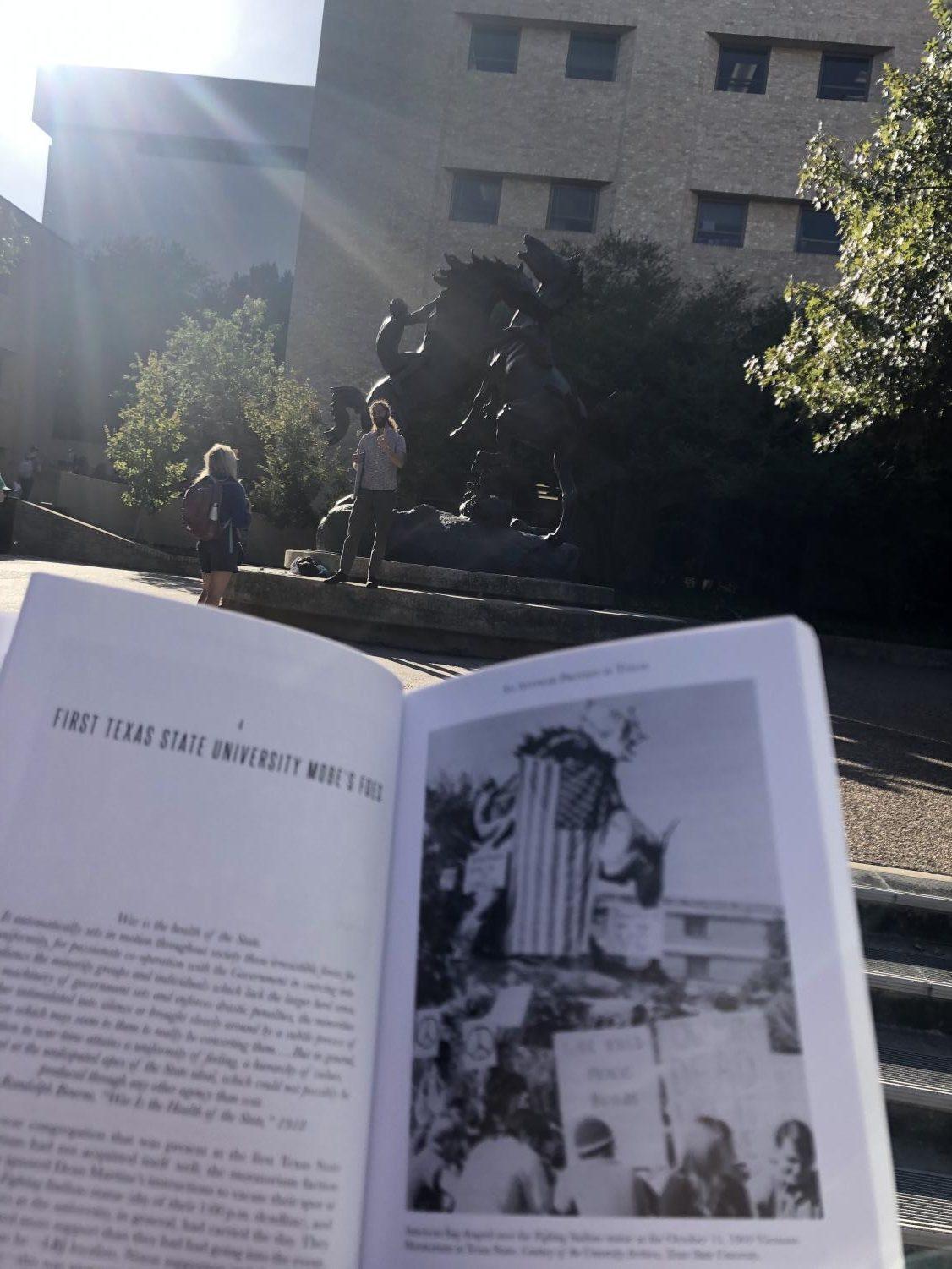

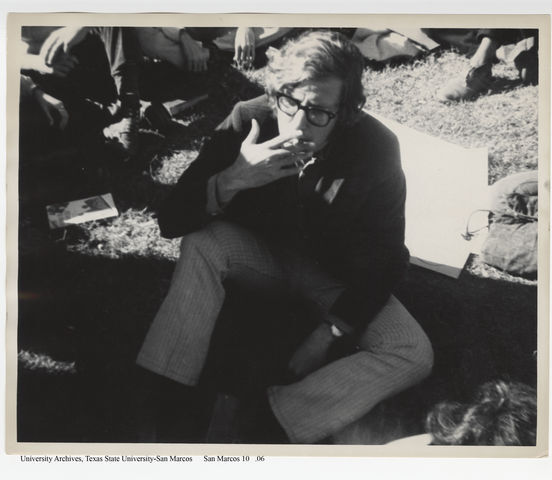

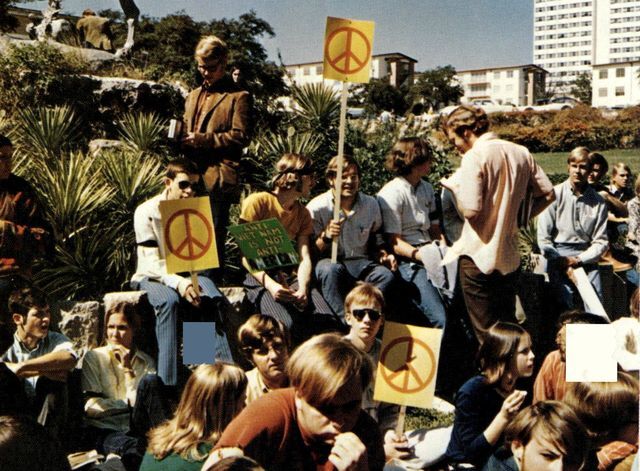

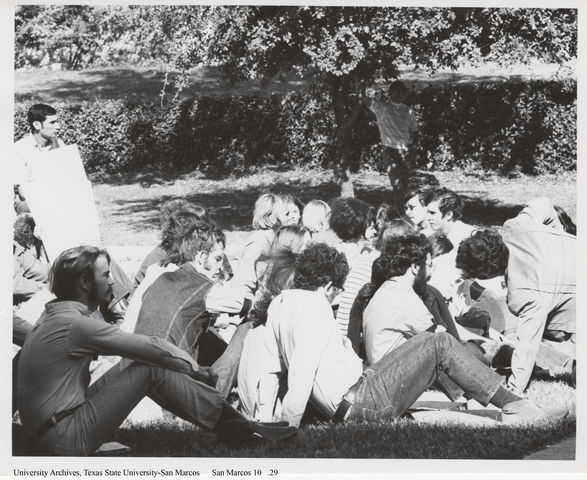

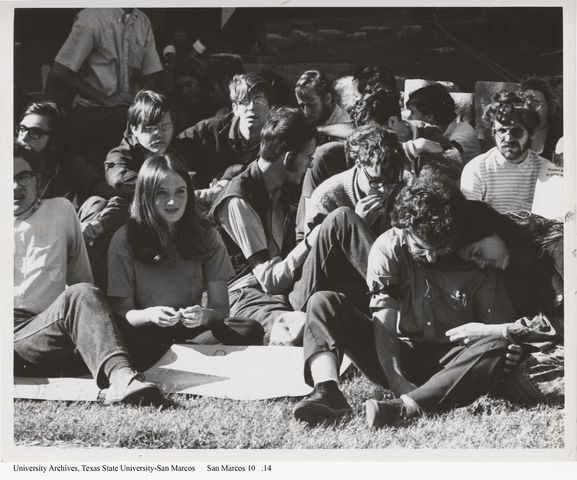

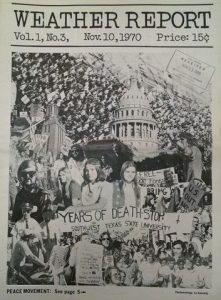

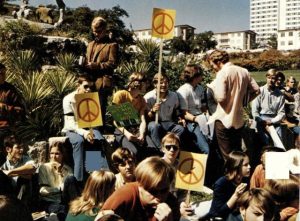

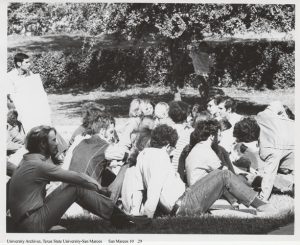

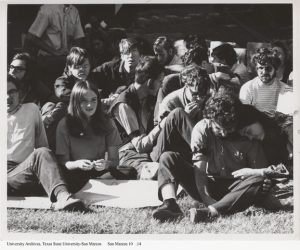

Quiet. Surrounded. Sitting cross-legged in the grass. There was no violence, no shouting and no one was hurt—not there. Nearly 9,000 miles away from the Vietnam War, hoards of students clad in black armbands gathered near the Fighting Stallions to peacefully protest the war on Nov. 13, 1969.

Students donned signs reading “How many dead will it take?” “44,000 U.S. Dead, for what?” and “War kills, peace builds.” Above them hung a U.S. flag and around them, peace signs galore.

The students were given three minutes by then Dean of Students Floyd Martine to clear the scene under threat of suspension. Campus security began to rope off the area.

Surrounded by a taunting and hostile crowd of fellow students shouting, “your three minutes are up,” students began to stand up.

Three minutes passed. Ten students remained.

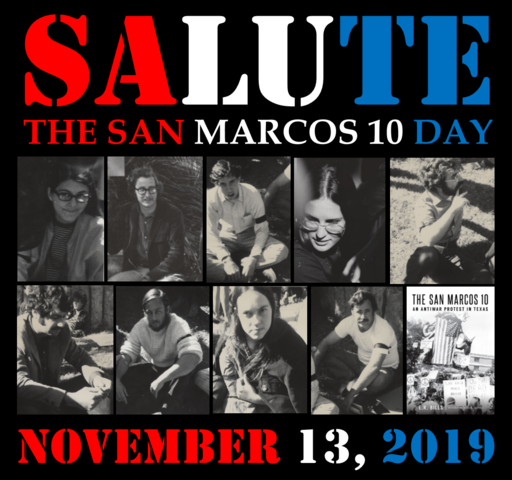

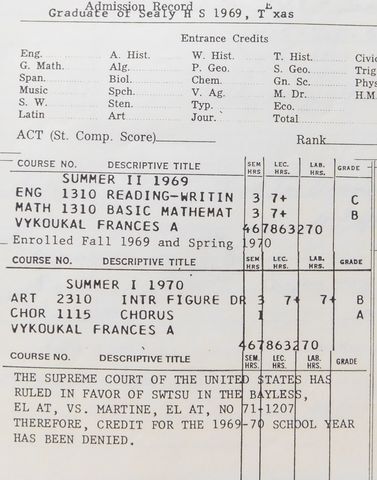

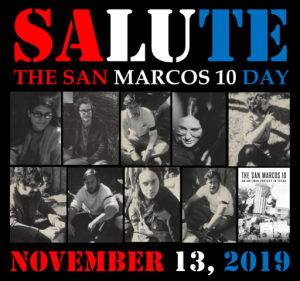

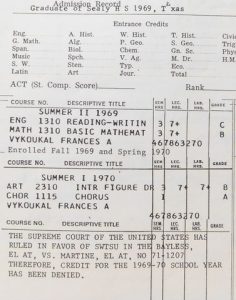

The administration began to collect names: David Bayless, a Vietnam veteran; Annie Burleson, Paul Cates, Al Henson, Michael Holman; David McConchie, who is now deceased, Murray Rosenwasser, Joseph Saranello, Sallie Ann Satagaj and Frances Vykoukal, also deceased. All 10 were suspended until fall 1970 with their credits from the past year canceled. None of them knew each other prior.

To commemorate the 50-year anniversary, the Honors College hosted a forum from 4-6 p.m. on Nov. 13. The same day was declared “Salute the San Marcos 10 Day” by Mayor Jane Hughson.

E.R. Bills, Texas State alumnus, journalist and author, has been following the story of the San Marcos 10 since attending university. His book, “The San Marcos 10: An Antiwar Protest in Texas” offers a comprehensive history of the event from start to finish. However, his initial story following the San Marcos 10 was written for Hillside Scene Magazine in 1989.

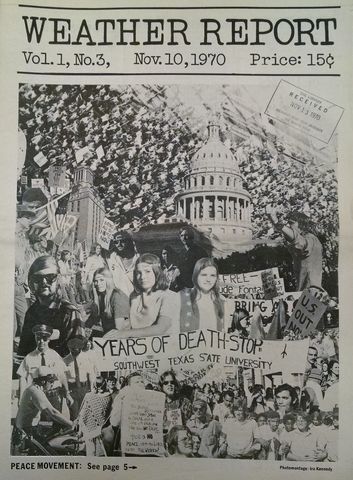

During the protests, Bill Cunningham, managing editor of The College Star (now The University Star) in 1969, was removed from the paper against his will for covering the events. Bills said the story is important because journalists were muzzled during the protests and still have the potential to be stifled now.

“The work journalists, in general, are trying to do is heroic,” Bills said. “You’re metaphorically getting punched in the mouth at every turn trying to do your job.”

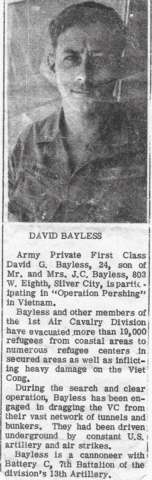

David Bayless

Bayless quit school in 1965 and hitchhiked to New York City to pursue a career in literature. He was romanced by the topic and loved John Steinbeck’s work.

Since he quit school, he was drafted into the army. Bayless had already served in Vietnam from 1966-1967 when the protest occurred 1969.

Bayless did not have an opinion on the war until he returned from his tour and a friend asked him if he realized what damage was being done.

“I felt used and abused (knowing) people had died for lie after lie,” Bayless said “We were not there to bring peace to Vietnam. We were not there to save civilization. We had all come in to take a piece of Vietnam.”

Bayless said he began to research, read about the topic and educate himself on the extent of the war. When he enrolled in school again, he decided to join the anti-war movement.

“We were destroying that country,” Bayless said. “We were destroying future children being born with Agent Orange poison we were dropping.”

Annie Burleson

Burleson said she was raised to stand up for what she believes in. This made it frustrating when the administration tried to enforce a free speech area between 5-7 p.m. at Old Main, which, “no one ever went to.”

“I’ve always been and still am basically a pacifist,” Burleson said. “I’m against war—all war.”

Burleson said it was a particularly scary time for men because the draft was so pervasive. They have no ill-will toward the people who got up during the three minutes. In fact, one of the protesters who left the scene was her boyfriend at the time.

“I didn’t blame anybody that left—not at all,” Burleson said. “I couldn’t get up. I had to stay. It was protesting the war but also feeling like we had the right to be there.”

Paul Cates

His family was disappointed in him when they found out about the protest. However, Cates said his father—a World War Two and Korean War veteran—was a hero in his eyes.

Cates said his family was open and talked about everything. This made him secure in his decision to protest, even though family members did not support him.

“I felt I had done the right thing, absolutely,” Cates said.

Cates made the decision to stay at the protest the night before, no matter what happened. He did not know what triggered the decision.

“I was very sure we were going to be kicked out of school,” Cates said. “I knew that. I had made my personal decision the night before that come what may, I would stay when we were told to leave.”

Even amid protesters being called “communists,” “cowards” and “thugs” by President Nixon, Cates said he never batted an eye.

“I never cease to be amazed at how strong people are,” Cates said. “We weren’t the San Marcos 10 when we sat down.”

Al Henson

Henson said he was nervous as to what his parents would say when he told them he was a protester; he was going to school on their dime. His father did not agree with his actions but supported his decision.

“That was the saving grace,” Henson said. “He very soon put me at ease about that and I was really proud and happy he did that for me.”

When Henson showed up to protest, he had already heard talk of reprisal toward protesters. Henson said even though he was considered a hippie, he was unfazed by the jeers and hollers from his peers.

“I didn’t have a lot of bad feelings about it all,” Henson said. “What was coming from the other side, I didn’t care. I was used to certain elements of the campus really looking down on my type.”

Henson said he even had friends who viewed the war completely different from him.

“I didn’t ever regret taking a stand,” Henson said. “I’m glad people recognize what it was. It feels good to have a day here in San Marcos.”

Michael Holman

Holman, still a San Marcos resident, gets up every morning to throw a rock in the direction of Old Main.

What he remembers most from the protest is being surrounded by angry “kickers,” what he described as “conservatives in cowboy gear.” He would sit and watch their boots go by.

Holman said even though he was highly opposed to the Vietnam War, that does not mean he lacks love for his country.

“I do take my country seriously and I am a patriot,” Holman said. “To me, protesting the war is about as patriotic as one can be.”

Holman said the campus administration at the time was in the wrong by instructing the group to move. Dean Martine telling the students they were the problem did not sit right with Holman.

“You are out there to make a statement and you want people to see you’re making a statement,” Holman said. “Otherwise, we could go out there and have sandwiches at midnight.”

While—in the literal sense—The San Marcos 10 became the group they are overnight, Holman said they rose to fame through a process of growth.

“I’m still a member of the San Marcos 10,” Holman said. “You can’t out-member a San Marcos 10 person.”

Murray Rosenwasser

Rosenwasser had also served in the military from 1965-1967. He said his outfit contributed to the occurrence of the My Lai Massacre in 1968, which was one of his main reasons to protest.

“We did everything for the soldiers,” Rosenwasser said. “We loved America. I’ve always loved this country and I still do. The important thing is to try and reach out to people who you disagree with–not hate people just because you disagree with them.”

Rosenwasser was especially close to the situation. He was friends, and later roommates, with Cunningham, who wrote an editorial condemning the administration prior to being removed from the paper.

“(Cunningham’s removal) kind of went under the radar,” Rosenwasser said. “The Star was definitely being censored at the time.”

Rosenwasser said he heard a story secondhand from when President Lyndon B. Johnson visited campus. The president was confronted about the protest and responded in favor of the San Marcos 10.

“Every day was an adventure,” Rosenwasser said. “A dangerous, exciting adventure.”

Joseph Saranello

Saranello said he was compelled to protest because he felt it was unjust to support such a great number of Americans being killed.

“The deaths were getting to the point where the news media, every week, was showing pictures of 200 or 300 Americans who had died,” Saranello said. “By 1969, it felt like this was just something we had any business being in.”

Due to the success of the October demonstration, Saranello said the administration was ruffled.

“We felt we had the right to be where we were as long as we were peaceful,” Saranello said. “I think the university felt really threatened.”

Sallie Ann Satagaj

Satagaj watched the body bags full of American soldiers on the evening news in the common room of her dorm. Satagaj, whose father was a Vietnam War medic, said she was overcome with sadness

“I cried and cried,” Satagaj said. “I couldn’t stand the death of all these young boys.”

Satagaj had once gone on a date with a man who had recently come back from his tour in Vietnam. The soldier could only sit in the corner and clutch the armrests on the chair. She said he did not say one word the entire evening.

“I was overwhelmed with how these boys were coming back,” Satagaj said. “I knew these men were being drafted left and right.”

Satagaj did not support the war and realized there were others with a like mind who would protest with her. The night before the event, she wrote her father from her dorm telling him she felt it was her duty to protest.

“I had no fear,” Satagaj said “I knew I was doing the right thing. I knew this is what America was founded on.”

Her father wrote back, “I know the Constitution will protect you and I support you all the way.”

The Aftermath

As the three minutes were ticking down, the crowd surrounding the protesters grew increasingly rowdy. Rosenwasser said he felt the crowd was close to becoming violent, but he was not scared of them.

“It was a real divided area—I didn’t hate them,” Rosenwasser said. “I talked to them. Our purpose was to reach out to them.”

Several other schools in Texas held demonstrations of their own, including a march at The University of Texas at Austin and a mock graveyard at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. At Texas State, the first national Anti-Vietnam War Moratorium had taken place a month prior, Oct. 15, in the same location. The demonstration garnered attention and was considered successful.

Holman, who jokingly refers to himself as the leader of the San Marcos 10, said at the time, Texas State was known as the safest place to send your daughter for college. This fact might have been why the administration was so quick to penalize the protesters. In 1969, there was a curfew and women had to live on campus until they turned 21 or were married.

“The school was promoted as a safe haven for your sons and daughters,” Holman said. “It was a different time. I worry about the new generation but then again, I’m sure my parents worried about us. I think when it comes to the right time, there will be people who will rise up.”

The 10 students were barred from enrolling in another Texas university for a year after being suspended. The group soon met with lawyers to fight the treatment they had been given. Their case was denied at every level of appeals and federal court ruled in favor of Texas State.

Only Supreme Court Justice William Douglas voted to review their case.

Tinker v. Des Moines was decided Feb. 24, 1969, and ruled in favor of students, allowing them freedom of speech in public schools. Even though the case was cited by the San Marcos 10’s lawyers, it was still thrown out.

“The San Marcos 10 were railroaded,” Bills said. “They should have won that case. The university engaged in maneuvers and machinations to win it, but they shouldn’t have gotten away with it.”

Though all eight of the remaining members of the San Marcos 10 appreciate the gesture, the holiday resulted in different feelings among the group. Rosenwasser said it was a weird feeling having a holiday named after them. Satagaj said she felt honored.

“That’s quite an honor,” Satagaj said. “I’m very appreciative. I thank the mayor and city council for doing that.”

Today, the Fighting Stallions statue represents a free speech landmark on campus—free of time restrictions and centered on campus.

“Stand up for something you believe in before it’s over,” Holman said. “You will have wasted your time if you don’t.”

Currently, no landmark stands for the protest that occurred Nov. 13, 1969. However, an application has been filed by Bills with the Texas Historical Commission to place a marker a few dozen yards over, at the original placement of the statue, from where the Fighting Stallions currently stand.

“If we’re as decent, fair-minded and big as (Texans claim), if we knew some of the stuff that had really gone on, we would look at things differently,” Bills said. “If we’re really decent, big-hearted, fair-minded folks, we would not be okay with how things are right now in our own state.”

This article was updated Nov. 21 to reflect Rosenwasser’s veteran status.

Categories:

San Marcos 10 revisit Texas State for 50-year protest anniversary

November 19, 2019

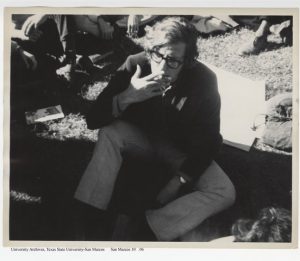

Photo courtesy of E.R. BillsA military image of David Bayless.

4

Donate to The University Star

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover