Trigger warning: this story contains mentions of dating violence.

Texas is the ninth-most dangerous state for online dating in the U.S., according to a study by the Privacy Journal.

From the likes of Tinder, Hinge and Bumble, dating apps are one of the most prominent ways to meet romantic partners – specifically among college-aged individuals.

The Privacy Journal ranked all 50 states on online dating risks, giving Texas a score of 51.53 out of 100. In Texas, reports linked to online dating include 4.4 romance scams, 278 cases of identity theft, 329 fraud incidents, 336 registered sex offenders, 781.5 cases of sexually transmitted diseases and 431.9 violent crimes.

How do these numbers play out at Texas State? To find out, The University Star asked Texas State students and alumni about their experiences with dating apps—what’s working, what’s not and what risks they’ve run into.

Ari Gill

Ari Gill, pre-nursing junior, has used Tinder and Hinge since arriving at Texas State but said online dating hasn’t led to any genuine connections in her experience.

“No one really wants to commit, these guys on dating apps they’ll hit you up only at 2 a.m. with a weird, dirty pickup line,” Gill said.

Students Against Violence Peer Educator Erin Whitney said there is sometimes an assumption that dating apps are only for sexual encounters, which can affect the culture surrounding it.

“That can affect somebody’s normalization of accepting things that they aren’t as comfortable with as fast… and they view the relationship and the app as a tool for sex that can then make it harder for them to recognize when their boundaries are being crossed,” Whitney said.

Initially, Gill was looking for something serious but had low expectations of finding that on Hinge—until she matched with someone who caught her attention.

Along with pictures of himself, the guy she matched with had “everyone is broken and hurt nowadays, no one wants anything real” written on his profile.

“Looking back that was probably the biggest red flag but at the time I was like ‘I want something real’ and so we matched and little did I know how messed up he would be,” Gill said.

While her parents were out of town, Gill invited him over to her house to meet in-person for the first time. That night was just the beginning of many where she’d end up in tears because of how he treated her.

“From then on he would say things that would purposefully make me cry only to pick me back up and it created this trauma bond where I associated feeling better with him even though he was the one who made me feel like [expletive] in the first place,” Gill said.

This continued for two months; she lied to her parents about seeing him, she wasn’t doing well in her summer classes and she said she lost all self-confidence because of him.

“I would have never met this person who left me feeling damaged if it wasn’t for Hinge,” Gill said. “It really opened my eyes to the fact that you do not really know anyone on dating apps, just what they choose to show you and that is smoke and mirrors.”

After blocking him, he continued to reach out through fake Instagram accounts for months, making Gill feel like he was always lurking in the background. She called this her worst experience, but not the only one—Gill said she frequently encountered people who made her uncomfortable and has reported several dating profiles.

According to Hinge’s help center, reporting a profile is anonymous and permanent, ensuring neither the reporter nor the reported individual will encounter each other’s profile again.

However, Nalani Pennick, healthcare administration senior, believes apps should have a system to track reported profiles and prevent those users from creating new ones.

Nalani Pennick

Pennick has also been on dating apps since moving into her on-campus dorm in 2022 to get familiar with the community.

“As a generation in a post-COVID world, we are more sucked into our phones and our technology just because we spent so long there and I think a lot of us don’t know how to approach people anymore so the apps break down that wall,” Pennick said.

An April 2020 study by Vanderbilt University found 30% of respondents reported increased dating app usage since the start of the pandemic.

While meeting someone behind a screen may make it easier to talk to someone, Pennick said the downside is feeling like you never get to know who the person truly is or what they’re looking for.

“The idea of being serious isn’t even the forethought in my mind,” Pennick said. “I’m more thinking ‘Do I have attraction to this person? Do we have a good connection? Could we talk? Could we be friends? Would my friends vibe with this person?’”

Like Gill, Pennick also reported people on Hinge because they’ve made her uncomfortable.

“This one time, I was saying I didn’t want to do anything and this person was showing me explicit videos with them and other people and I was like this is not cool,” Pennick said.

Pennick doesn’t define her sexuality but recognizes the added risks for the queer community on dating apps, noting that members of the community are often fetishized.

According to the Pew Research Center, lesbian, gay and bisexual (LGB) adults use dating apps 27% more than straight adults. But with that increase comes greater risks.

The research also showed 69% of LGB adults reported experiencing some form of harassment on dating apps.

“We do have some people on campus that don’t believe in those identities and they can target you for that, especially with the location aspect of the app,” Pennick said.

Another common trend Pennick sees on the app is older men targeting younger girls, which she experienced when she was 18.

Kelsey Banton, violence prevention program manager at Texas State’s health promotion services said because of experiences like Pennick’s, it is important for people to set boundaries and intentions.

“Freshmen women and individuals who identify as women, are disproportionately affected by sexual assault,” Banton said. “In their first four semesters are when most individuals experience a sexual assault during their whole college experience and that number is so disproportionate.”

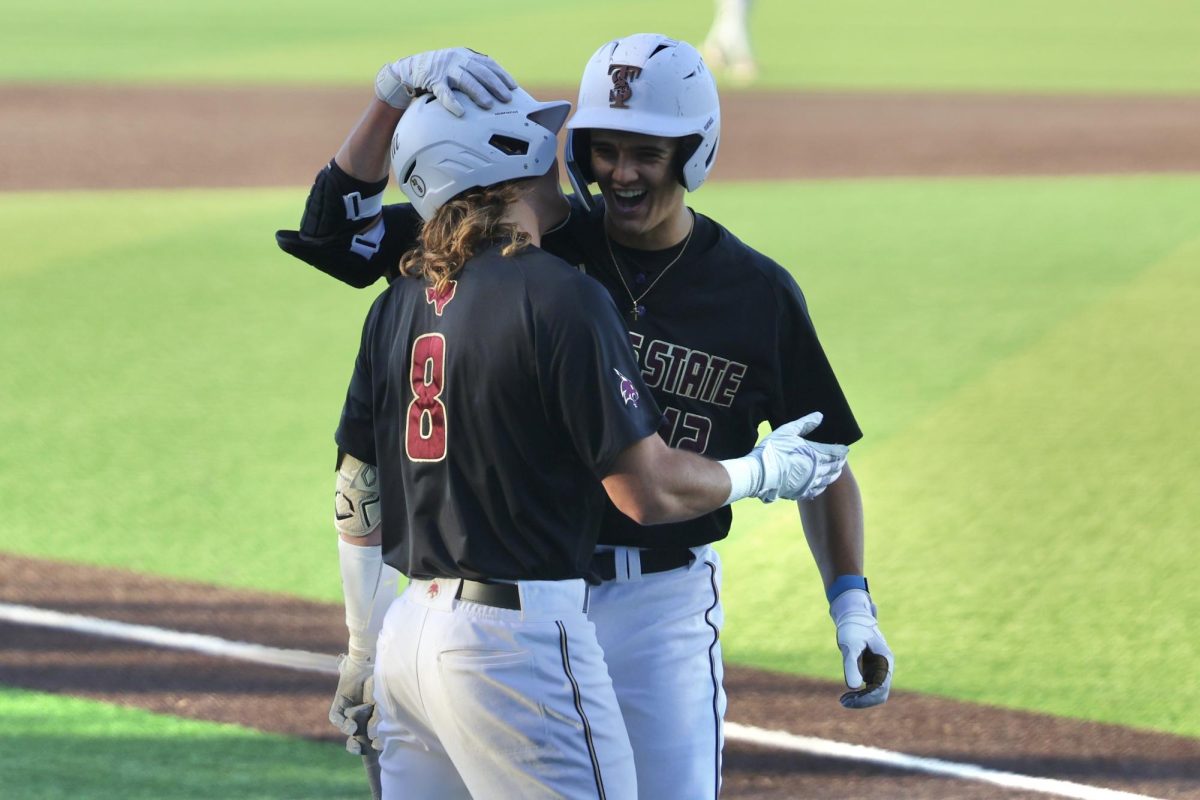

Online dating has its dark side, but for Texas State alumnus Grant Barber, Tinder led him to his now wife.

Grant Barber

Grant downloaded Tinder in 2012, during his sophomore year at Texas State, the same year the app was founded.

When Grant first started using Tinder, it felt like uncharted territory. That changed after he spent weeks talking to a girl he was interested in—only for her to suddenly unmatch him and delete her account.

“That changed my mindset to this is not real life, have fun with it and don’t take it too seriously,” Grant said. “If you’re looking for something in particular, you’re probably not going to find it. Just go with the flow, see what happens and that made it a much more enjoyable experience for me.”

Grant had been swiping on dating apps for eight years before he came across Asta Barber’s profile, another Texas State alumna, during the height of the pandemic.

He said both his and Asta’s profiles showcased their “silly sides,” which is what led him to swipe right.

“The more self-aware of who you are, I think the more yourself shows through, no matter what you put out in the world and unfortunately, a lot of people don’t know themselves but she did,” Grant said.

For their first date in September 2020, Grant cooked dinner for Asta at his home. He knew early on he wanted to be with her, but it took time to reach that point, so he continued talking to other women in the meantime.

“I said to a few of them ‘Hey, I’m happy to hang out with you but just a heads up there is one girl that I’m very interested in but she’s not fully committed to me and I’m not fully committed to her, but if we decide it’s go time I’m gone,’” Grant said.

Eventually, they decided to officially date after Asta left her boyfriend at the time for Grant. They got married this year.

Grant and Asta would have never met if it weren’t for Tinder, he said. Despite spending years on the same campus at Texas State, they never crossed paths until after graduation, when both found themselves swiping through the app – but they had varying experiences on the app.

“Situations definitely can happen where the man is in danger [on dating apps], but women are going to, unfortunately, be more vulnerable in situations,” Grant said.

According to the Pew Research Center, 66% of women aged 18-49 have experienced online harassment, including receiving unsolicited sexually explicit messages, persistent contact after rejecting someone, offensive name-calling or threats of physical harm—compared to 36% of men.

While Grant and Asta’s story shows that dating apps can lead to lasting connections, not everyone is as fortunate.

Banton recommends getting to know someone before meeting in person and suggests choosing a public place for the first meeting.

“They can maybe video chat a couple of times. They could play a game just doing something where they’re not together physically, but they’re still bonding or getting to know each other in some capacity,” Banton said.

If someone wants to take legal action regarding sexual violence, SAV recommends reaching out to the Texas Advocacy Project, a pro bono legal group specializing in cases such as non-consensual image sharing and stalking.

Other resources include the Hays Caldwell Women’s Center, University Police Department Bobcat Safe Rides and the Counseling Center.

“Sometimes we put up these really scary walls around how to set boundaries around sex, but it’s really similar to how we set boundaries in our everyday life and it’s important to practice boundary setting in all relationships,” Banton said.