For some Indigenous peoples, an Election Night poll by CNN categorizing race by white, Latinx, Black, Asian and “something else,” served as an indication of how an Indigenous heritage often comes with a feeling of having one’s very existence erased.

“There’s a certain resilience in being able to make a joke of it and being able to say, ‘well we’ve been called everything so ‘something else’ doesn’t bother me.’ That’s something that’s really cool to me, to see the continuance of Indigenous resilience,” said Adam Alejandro, a developmental education doctoral student. “It’s another example of people of color being presented as less than human.”

Race categorizations in polls are one of the many avenues where Indigenous people see themselves being misrepresented. Alejandro remembers walking into a sophomore-level American Indian program class (the name of which has since been changed) in 2015 at his undergraduate alma mater, Cornell University. The professor was Indigenous, as were several of Alejandro’s classmates, none of whom were expecting what came next.

“It’s funny in retrospect, but a very stereotypical northeastern non-Indigenous female student comes in with her Starbucks and sits down,” Alejandro said. “We begin a conversation of contemporary indigeneity. She raises her hand and says ‘do Indigenous people still exist?’”

Alejandro’s professor handled the situation with humor and lightheartedness, explaining that yes, Indigenous people do everyday things like go to Walmart and McDonald’s, and no, they do not do those things wearing buckskins.

The professor explained it was not surprising the student had that misconception; the most contemporary images people might see of Indigenous people are from the late 1800s. That coupled with the fact that movies tend to stereotype Indigenous people as living in teepees, riding horses and having long hair creates a lack of understanding of modern-day indigeneity.

Though Alejandro is able to laugh about that classroom experience now, it has stayed with him through the years and is a motivating factor in the work he does to help Indigenous students succeed academically.

“When I think of my work as a doc[toral] student in education, and what my purpose is, the biggest thing is continuing to show and educate people that we have contemporary issues, especially in education, that are barriers,” Alejandro said. “There are systemic barriers for Indigenous students that are harder to overcome without support. That’s really why I do the work I do.”

Alejandro works closely with Maria Rocha and Dr. Mario Garza, the executive director and chair of the board of elders for the local nonprofit Indigenous Cultures Institute. For Rocha and Garza, the work of bringing justice to Indigenous communities mainly comes in the form of two overarching efforts: Education and repatriation.

“Our mission is to provide information to the public about our Indigenous people here in Texas and northern Mexico,” Rocha said. “The Coahuiltecan people were the original Texas Native Americans who have lived here for 14,000 years continuously. We never left our homeland, so the people that you know today as Hispanics, who their history has always been in Texas, they are most likely Coahuiltecan people. They just are not aware of their heritage because our history was stolen from us.”

The other large part of Rocha and Garza’s work is repatriation, which is the process of returning a person to their homeland.

In the case of the Indigenous Cultures Institute, that means pleading with various academic institutions to release the remains of Indigenous people, which are often dug up by archaeological teams and stored in cardboard boxes, where they sit neglected for years on end.

“It has always been against the law to disturb a human grave. But every day somebody digs up [the] remains of our people from our graves,” Garza said. “Then they sell them overseas or to museums or universities. Nationwide, there’s over 7 million remains of our people that are in cardboard boxes. They don’t want to give them to us.”

This is deeply disturbing to Garza and Rocha, as death holds spiritual importance in Indigenous beliefs. Indigenous tradition states that a person’s body reintegrates into Mother Earth upon death, while her, his or their spirit ascends to the cosmos as part of a spiritual journey. Digging up a body disrupts that process, preventing Indigenous ancestors from ever finding peace.

“They have our ancestors as collections, just like you have a collection of salt and pepper shakers. We try to explain to them, what if we went to your grandmother’s grave and dug her up and said ‘We found her, she’s ours. You can’t have her, we’re going to keep her forever,'” Rocha said. “It’s hard for them to understand. We have a different connection to our ancestors.”

Although there is still a mountain of work to be done, the institute has rejoiced in some notable victories over the years. The institute has maintained a good relationship with Texas State and the archaeological department assisting in the reacquisition and reburying of Indigenous remains.

“All of the ancestors that Texas State University had, have now been repatriated. Good for Texas State University, leading by example to do the right thing,” Rocha said.

The work of the Indigenous Cultures Institute is sustained by moments of joy, such as successful repatriation and annual celebrations.

In years not marked by the COVID-19 pandemic, the institute hosts a Powwow, a celebration featuring dancing, vendors, traditional food, activities for children, presentations and togetherness.

The community also comes together every year for a Sacred Springs ceremony in which it receives blessings from the water, traditionally thought of as a life source.

This balance of keeping sacred, centuries-old traditions alive while fostering a modern understanding of indigeneity is the legacy Garza and Rocha will one day pass on to Alejandro, who is slated to eventually take over as director of the Indigenous Cultures Institute.

Until then, he will continue encouraging people to educate themselves, read Indigenous authors and consider that there are Indigenous people all around them, whether they know it or not.

“Indigenous people are still here. We are modern people. We haven’t disappeared, we haven’t all been killed off or moved to reservations,” Alejandro said. “There are Native communities. We are doing really awesome work in academia. Just like anybody else, we become doctors, educators and anything that anybody else can.”

For more information about the Indigenous Cultures Institute visit its website.

Categories:

Indigenous communities seek to create understanding of history, modernity

Leanne Castro, Life and Arts Contributor

November 18, 2020

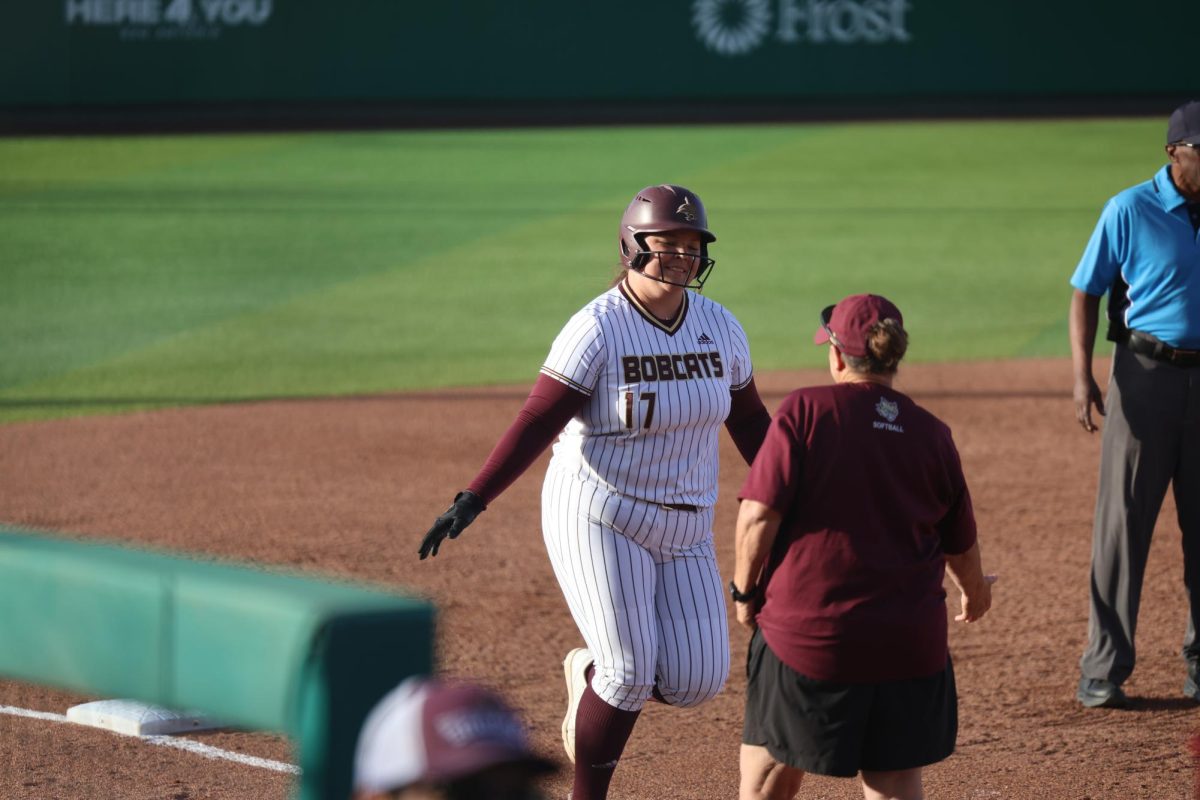

A participant in the Fancy Shall Dancer Competition performs at the Sacred Springs Powwow at the Meadows Center, Nov. 2018, in San Marcos.

0

Donate to The University Star

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover