Joshua Castro knew he wanted to serve in the Peace Corps in third grade. His class had a pen pal in the Peace Corps who would tell them stories about the different ways they had to adapt to day-to-day life, which included living in a country that experienced extreme drought and learning to take showers with only two liters of water.

“As a kid, you don’t understand how everything isn’t what you experience, how things can be so different on the other side of the world,” said Castro, regional and Texas State recruiter for the Peace Corps. “I was very interested, and I was always waiting for that volunteer to send their letters. That’s what first really got me interested in Peace Corps.”

The Peace Corps is a service organization established by President John F. Kennedy in 1961 as a way for Americans to support underserved communities all over the world in their educational, environmental, economic and health goals. Since its creation, more than 240,000 volunteers have served in over 142 countries.

The letters Castro’s class received from one of those 240,000 volunteers planted the early seeds of Peace Corps service in his head, but it was the stories he heard years later from Dr. Michael Andreu, his graduate adviser in the Forestry Department at the University of Florida, that caused the idea to blossom into reality.

Andreu served as a Peace Corps volunteer in West Africa in the early 90s and can still remember the sounds of his tiny village in Niger waking up.

He recalls how first the donkeys would start braying, which would upset the camels, who in turn would make morning calls of their own. Next came the stirring of his neighbors, all of whom lived crammed together in walled compounds, making privacy virtually impossible. Finally, the Muslim call to prayer would ring out, and thus the day would officially begin.

Volunteers typically serve for 27 months, with the first three months consisting of intensive training, particularly in the language they will be speaking. For Andreu, this meant learning Zarma, a non-written language that can only be learned by speaking.

This entirely new language coupled with the fact that his village did not have running water or electricity meant he was in for quite the culture shock. Once the initial shock wore off, though, he found himself realizing that despite their drastically different way of life, the people in his community were not merely surviving; they were thriving.

“They loved each other, and they were happy, and they appreciated life,” Andreu said. “To come back home afterward and see how much we have here, and often we don’t appreciate how amazing our lives are here, that was one of the biggest things that I [took] home. We are very, very fortunate, and we should find ways to appreciate and respect that and not take it for granted.”

To Andreu, it is important to pass on gratitude for even the most commonplace things like twisting a knob to get clean drinking water or flipping a switch to get light. He works hard to instill this lesson in his son and has also passed it on to students of his, like Castro.

After hearing stories like this from Andreu’s time in the Peace Corps, Castro realized it was ‘now or never.’ The next thing he knew, he was headed to Paraguay.

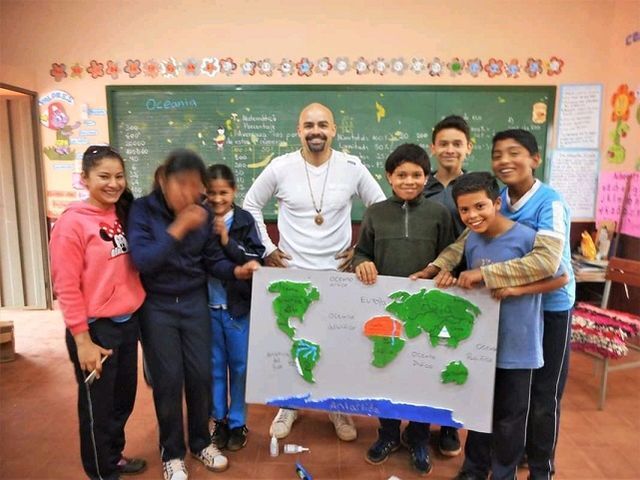

During his two years in Paraguay between 2015-2017, he worked with local schoolchildren on a wide range of environmental issues, like reforestation and beautification, with a particular emphasis on trash management.

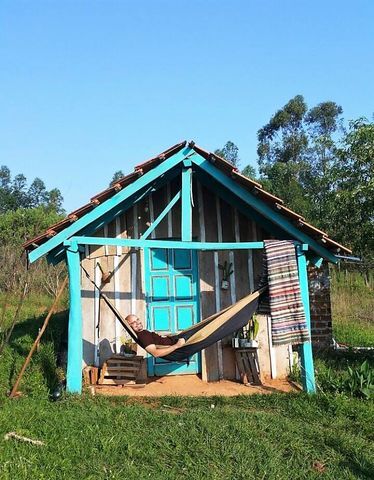

There was no system of trash collection in his community, meaning people would often burn their waste. When he was not working with kids or spending time cultivating relationships (he still keeps in touch with his host family and even visited them last Christmas), he could be found at his house—a wooden hut with gaps in the panels, no hot water and no kitchen. He went into the Peace Corps wanting to be challenged, and that is exactly what he got.

“It can wear you down,” Castro said. “But I signed up for that, and at the end of every day, I was so proud. It was such an incredible feeling.”

When he eventually returned home, it felt natural to continue working for the organization, this time in a recruiting capacity. He loves seeing people’s eyes light up when they learn about the Peace Corps and gets jealous when working with students who are applying for an experience that meant so much to him.

In a truly full-circle moment, he was a pen pal to a third-grade class during his service, sharing stories with them about cultural differences in Paraguay, like the custom of standing in the street outside someone’s house and clapping to get their attention instead of knocking on their front door.

His recruiting duties are still in full swing, with the Peace Corps planning to send volunteers back into the field in 2021 with extra COVID-19 precautions, like mandatory testing and a 14-day quarantine upon arrival in the host country.

“My advice to anyone interested in [the] Peace Corps is to just do it,” Castro said. “Go for it.”

Senior Diversity Recruiter for the Peace Corps Natalie Felton shares Castro’s enthusiasm for spreading awareness of the organization, though her own awareness of the existence of the Peace Corps did not come until much later in life.

She was teaching English in southern France after college when she was invited to dinner with a mutual friend who had just returned from service in Senegal.

“In comes this Jewish girl with African garb on, and I’m like, there’s a story there,” Felton said. “I [wanted] to know everything. That night, I was on the computer researching Peace Corps.”

Felton’s interest in the organization grew as the friend shared stories. Her research that night would eventually lead her to apply and be accepted as a volunteer.

Felton was placed in a teaching role in the island nation of the Republic of Vanuatu in the South Pacific Ocean. She fell so deeply in love with her work and her small community of fewer than a thousand people that she ended up staying for four years between 2011-2015, which is double the amount of time for a typical Peace Corps contract.

Her life in Vanuatu was wildly different from her life back in her hometown of Chicago. Her home of bamboo walls and a thatched roof sat on top a hill 10 minutes away from the ocean. At night, she could hear the waves.

Then there were the logistics of her day-to-day necessities like eating.

“I had no consistent running tap water; I didn’t have electricity or gas,” Felton said. “I cooked over a fire for two years. My host sister helped me practice that. It’s a bit of a more rustic way of camping.”

In fact, she honed her fire building skills so sharply during those years that she is now the designated fire master on her family’s annual camping trips.

Her projects eventually reached their natural end, and it was time for her to return to the states. On the day of her departure, she remembers her face being soaked— both from the falling rain and her own falling tears.

Anyone interested in learning more about the Peace Corps can visit its website. Joshua Castro can be reached at jcastro@peacecorps.gov.

Categories:

Peace Corps leaves volunteers with lifetime worth of stories

Leanne Castro, Life and Arts Contributor

October 7, 2020

0

Donate to The University Star

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover