As discussions on whether to preserve or remove Cape’s Dam continue, locals and community leaders have called into question the history of Thompson’s Islands.

The argument pertains to whether slave labor was used to build a sawmill and gristmill in the 1850s at the location of Cape’s Dam.

In a Feb. 3, 2019 San Marcos Daily Record op-ed titled “Lets Acknowledge the Role of Slave Labor,” San Marcos Parks and Recreation advisory board member Jordan Buckley wrote, “Don’t take my word for it—park behind The Woods on River Road, carefully cross the street and examine for yourself. Multiple Cape’s Dam preservationists in recent days have publicly denied the contributions of

individuals enslaved by the Thompson family.”

Buckley was referring to the Thompson’s Islands historical marker at Stokes Park which mentions the use of slave labor to build a mill near the site of Cape’s Dam.

Following Buckley’s op-ed, Hays County Historical Commission Chair Kate Johnson wrote a letter to the editor released on Feb. 6, 2019 in the San Marcos Daily Record in which she explained that the current historical marker at Cape’s Dam is a “mistake.”

“The Hays County Historical Commission realizes mistakes were made in the past and memorialized on historical markers. Even the Texas Historical Commission understands this and has tried to correct errors when discovered in the more than 16,000 historical markers across the state as funds and staffing allow. The price of a historical marker is currently $1,875. Unfortunately, correcting historical facts is an expensive undertaking,” Johnson stated in the letter.

Thompson’s Islands is named after William A. Thompson, a cotton planter, ginner and slave owner who owned the land where Stokes Park is today.

According to an 1860 U.S federal slave schedule from an Ancestry site, Thompson owned 25 African-American slaves which ranged in age from a four-month-old female infant to a 70-year-old male.

The historical marker was placed in 1994 after a late descendant of Thompson, Kathryn Thompson-Rich, submitted an essay to the Hays County Historical Commission detailing her great-great grandfather’s history.

She explained that Thompson moved to Caldwell County in the 1850s where he allegedly struck a gentleman’s agreement with the landowners of what is now Thompson’s Islands, John McGehee and Henry Davis, for mutual use of the water and land so they could begin building a milling enterprise. Currently, there is no official documentation that shows the alleged transaction.

Thompson-Rich wrote, “A ditch was built to channel the water to the mill by the manpower of slaves.”

According to Hays County Courthouse deeds, construction of Cape’s Dam did not begin until 1867, after the emancipation of slaves in Texas in 1865. However, the center of this debate is whether Thompson used his slaves to build this alleged milling operation in the 1850s.

Author of “Claiming Sunday: The Story of a Texas Slave Community” Joleene Maddox Snider, former Texas State history professor, claims there is evidence to prove Thompson slaves built a sawmill and gristmill in the 1850s with permission of landowners Davis and McGehee.

Snider released a written report Jan. 7 detailing her evidence and presented it to the San Marcos City Council during public comment session.

According to Snider, Thompson-Rich’s account is copious in detail and reads too credibly to be dismissed, despite opposing forces arguing that Thompson-Rich could not have provided a credible account because she never knew her great-great-grandfather personally.

“I was unwilling to completely discount the Thompson-Rich narrative. Being elderly does not automatically discount her account. Historians long in the tooth can be competent and astute,” Snider stated in the report.

Snider said gentleman agreements similar to that as outlined by Thompson-Rich, were common in the 1800s and usually involved some sort of work in return.

Snider argues that because of the prevalence of slavery in the south during the 1850s, it would be fair to assume Thompson would have had his slaves do any of his physical labor.

“Anything that was built before 1865 was probably built with at least some slave labor, particularly something as large as a mill on a river,” Snider said. “Not accepting the fact or recognizing the fact that slaves did most of the physical labor exhibits what is, in my opinion, a profound ignorance of slavery in Texas.”

Snider cites a document written in 1948 by writer and historian Dudley R. Dobie titled “Brief History of San Marcos and Hays County” published in the San Marcos Daily Record. The document was pulled from Dudley’s 1932 thesis done at The University of Texas at Austin under American historian Walter Prescott Webb.

Dudley writes, “In an interview with the late A.D McGehee, the writer was told that the first cotton gin was owned and operated by Dr. (W.A) Thompson. It was combined with a sawmill and stood on the San Marcos River at that point now known as Thompson’s Island. The gin was constructed in the early 1850s and its power consisted of eight mules.”

A second reference to Thompson states, “Dr. H.W Davis, Stephen McKie, and Dr. William Thompson were the owners of a sawmill located at what is now Thompson’s Island. This mill was built about 1855.”

The thesis, which is currently available for viewing in The Wittliff Collections at Texas State, stands as evidence that there was activity at Thompson’s Islands prior to 1865, according to Snider.

“Both references predate the Thompson-Rich document by forty years, however, for the most part, they support Thompson-Rich’s writings,” Snider stated in the report.

A deed from 1867 shows the purchase of Thompson’s Islands by Thompson from a Catherine Pryor. An agreement signed the same year forms a partnership between Thompson, Davis and a Stephen McKie outlining how they are going to construct Cape’s Dam and the mill race.

According to Snider, the partnership agreement signed in 1867 was when Thompson built upon the operation he allegedly had in the 1850s.

Former Hays County Historical Commission Chair Lila Knight, who was chair during the official unveiling of the marker in 1994, has been on the opposite side of this debate, arguing that Thompson-Rich is not credible and there could not have been a gentleman’s agreement between Thompson, McGeHee and Davis.

“Most of what (Kathryn Thompson-Rich) went on was information that had been handed down by her family, and the man who built the dam was her great-great-grandfather, so she never knew him,” Knight said. “It’s easy to get things wrong and get facts mixed up.”

Although Knight was chair of the commission, authorizations of the Thompson’s Islands marker were done under marker chair Francis Stovall. Knight said she had no involvement in the approval of the marker.

“I so failed as chair of the Hays County Historical Commission not to make certain that the information provided to the Texas Historical Commission was correct. I trusted Francis Stovall,” Knight said.

According to Knight, a gentleman agreement is considered to be an oral agreement, thus it is impossible to know whether the agreement occurred.

Since Thompson did not officially purchase Thompson’s Islands and sign the partnership agreement until after 1865, Knight said it proves that slavery could not have been associated.

“I understand the importance of oral history, but it can still be wrong, and documents don’t lie, and they’re not mistaken,” Knight said.

Additionally, Knight said there is no official documentation that says McGeHee and Davis owned any land near Thompson’s Islands.

“When you start making statements that slaves built it, but you haven’t bothered to do the research on when it was actually built, then that’s a huge mistake of history and historical fact,” Knight said.

Johnson said approximately one-third of the total historical markers in Texas are considered to be incorrect, most of them from the 1970s and 1980s. According to Johnson, the information used was based on oral history, not primary sources.

Although Johnson said oral history like that of Thompson-Rich is important, she said it should not be treated as a primary source of documentation.

“(The Thompson-Rich essay) is a tool to be used but you need a lot more than just one shovel to create anything,” Johnson said. “You need multiple tools to dig or to get anywhere you want to go but I need a lot more documentation then just hearsay.”

According to Johnson, the commission is conducting its own separate investigation into the history of Thompson’s Islands, however, because the Texas Historical Commission has no current foundry to produce historical markers, the 2020 application cycle has been postponed and no markers can be made at this time.

The San Marcos City Council has yet to decide whether to destroy Cape’s Dam or preserve it as a historical marker. During a work session on Jan. 7, the council announced it was going to continue studies into the dam.

Both Snider and Knight said they are unconcerned about the council’s ultimate decision.

“I don’t care what they do; they can take the dam out of the river and turn it to its original course, or they can keep it because it’s historical, just be honest about who did the work,” Snider said.

Knight admits it is possible Thompson slaves could have built a milling enterprise in the 1850s at a different location, but without proper documentation, she said she is going to stick with the facts.

“The work that (Francis Stovall and Kathryn Thompson-Rich) did was very important, but if all you ever do is rely on the research that was done in the last century, then you’re not learning anything new. You have to take their work and build on it and not just accept everything they did as fact,” Knight said.

President of the Calaboose African American History Museum Elvin Holt, Texas State English professor, said he supports Snider’s findings and believes the statement on the historical marker is correct, however, he is open to any new evidence.

“As an African American, I come from a culture that privileges oral history, although I know many people prefer documentary evidence to oral history alone. Fortunately, Ms. Snider’s research uncovered credible documents that corroborate details set forth in Ms. Kathryn Thompson-Rich’s summary of her recollections of family history,” Holt said. “However, I maintain an open mind on this issue, and I welcome compelling new evidence that challenges Ms. Rich’s recollections.”

Categories:

Slave labor dispute floods Cape’s Dam

February 6, 2020

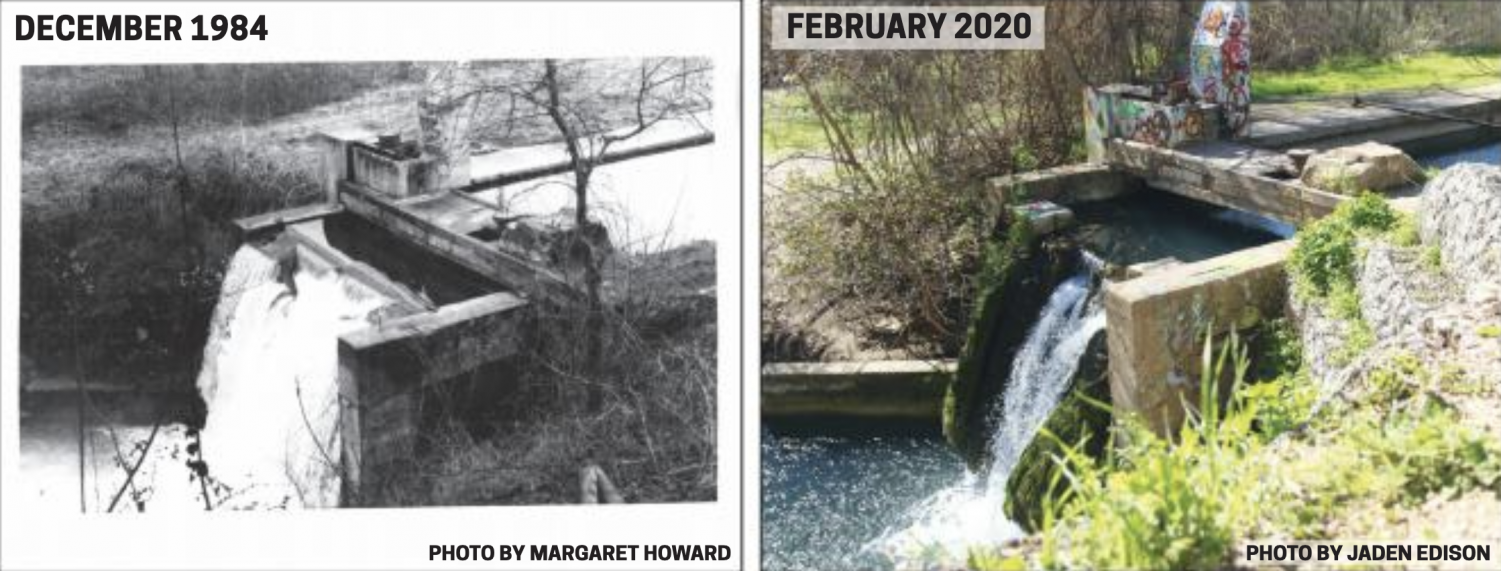

Jaden EdisonThe history of Cape’s Dam at Thompson Island remains unclear decades after its construction. Debates over whether or not slave labor was involved when the dam was built continue to take place. Moreover, the San Marcos City Council has yet to decide whether or not the dam will be destroyed or preserved as a historical marker. (This photo was taken Feb. 1, 2020)

0

Donate to The University Star

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover