Before stepping foot into the clinical lab of Ascension Seton Hays Hospital in Kyle, Gilbert Swink sat fully clothed in personal protective equipment, including a mask and a face shield, ready to run another set of COVID-19 tests.

Like many health care workers, Swink, a Texas State alumnus and medical lab scientist, has been working nonstop on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic. His work along with many other clinical laboratory professionals across the country is the work of the unseen, keeping turnaround rates for testing as low as possible.

As of early January, the U.S. laboratory medicine workforce has performed nearly 270,000,000 COVID-19 tests, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Behind the numbers and often lost in the shadows are the scientists working tirelessly to make sure a high level of testing continues for the indefinite future.

Since last spring, Swink has mastered the art of COVID-19 testing; however, his success comes with plenty of roadblocks standing in the way.

“When we first started, we had to pretty much come up with our own kits for specimen collection because, you know, supply was very short because of manufacturing,” Swink says.

Once rapid testing analyzers became available, Swink became one of the first medical laboratory scientists at his hospital to learn how to use them. He then trained the rest of the laboratory staff to use the analyzers properly to maximize efficiency in the lab.

Because of minimal equipment, fast-growing demand for testing and the brief gap of time available to conduct tests, Swink says medical laboratory staff is becoming overwhelmed.

“Once you’re in the room, you can’t leave until all the specimens are completed. And if you’re just constantly getting specimens, that’s one person in that room doing all the testing,” Swink says.

Testing for COVID-19 is only at the surface of what medical laboratory professionals do. Every year, medical laboratory professionals like Swink are responsible for over 13 billion medical tests, according to the Commission on Office Laboratory Accreditation (COLA).

The results of these tests are critical to patients’ overall health, as their results drive nearly two-thirds of all medical decisions doctors or other healthcare professionals make each day, according to COLA.

“Without us, your doctors are just guessing,” Swink says. “They might have an inclination as to what’s wrong with you, but without a definitive laboratory test, to either rule out or confirm that, they don’t know.”

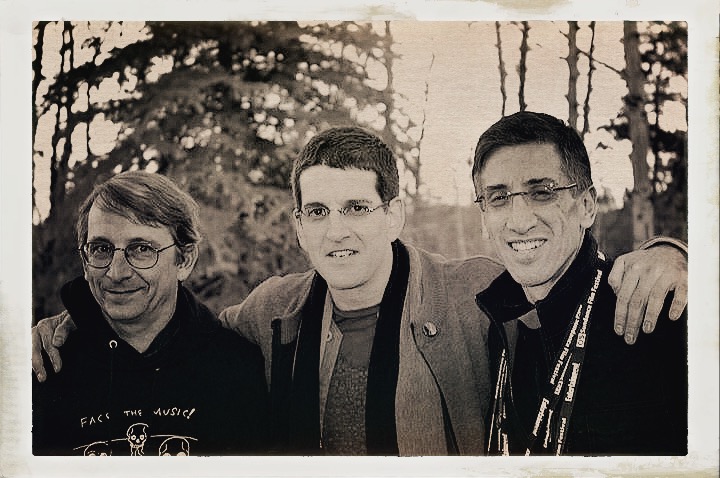

Dr. Rodney E. Rohde, professor and chair of Texas State’s Clinical Laboratory Science Program (CLS), graduated from Texas State with degrees in microbiology and virology; however, he did not find out about the clinical laboratory profession until after he left the university.

“It’s a profession that most people don’t really notice because we are behind the scenes, but it’s really the cornerstone of healthcare with respect to getting things right,” Rohde says.

The tests these professionals are in charge of ultimately decide the treatment for patients with heart problems, infections, cancer and a number of other diseases.

Although the pandemic has brought to light just how vital clinical lab scientists are to healthcare systems, staff shortages and limited program availability are also critical issues.

According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, there are an estimated 337,800 medical laboratory professionals currently working in the U.S.— a country that has a population exceeding 300 million.

Currently, the number of medical laboratory scientist and technician training programs in the U.S. is decreasing, according to the American Society for Clinical Pathology. Rohde says a lack of awareness in schools and in the medical field about what medical laboratory scientists do, combined with a limited number of programs to prepare these professionals, have contributed to the current state of the profession.

“It’s always an uphill battle to try to get some of these programs put into place,” Rohde says.

Each year, Rohde and his colleagues lobby in Washington D.C. and at the state level to promote an increase in funding to the existing CLS programs in hopes of seeing them grow in numbers.

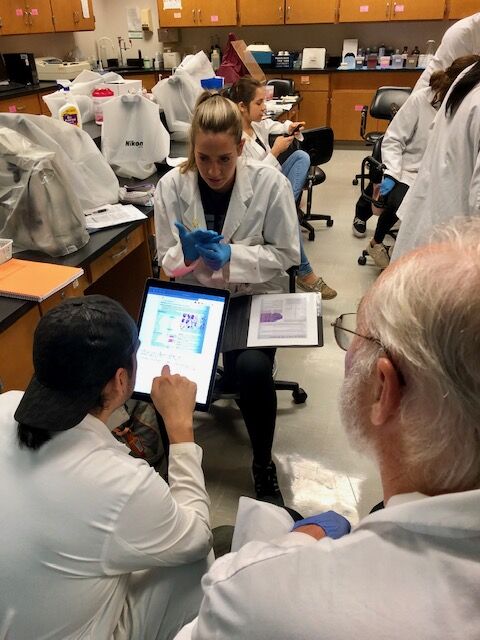

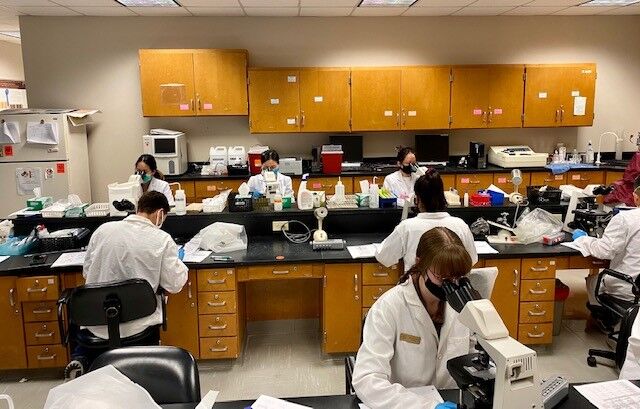

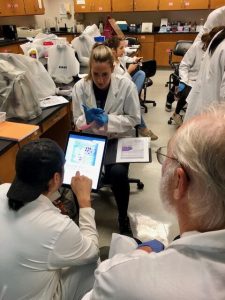

Students who are part of the CLS program at Texas State are required to complete clinical placements, or rotations, in local hospitals their senior year. However, because of limited funding and staff available at those hospitals, most will only take one student per semester. This has limited the number of students the CLS program can admit to only 20 a year.

One of those students is Anahie Segura, a CLS senior. Segura is getting ready to start her clinical rotations in the spring; however, due to the lack of hospital staff available to train these future professionals, there has been some uncertainty over whether students like Segura will be able to physically attend their placements.

“You never think a pandemic will happen in your lifetime and now it’s scary because you have all these thoughts about whether you’ll be able to finish your program and graduate in time,” Segura says.

Segura says she knew early on her true calling was to help save lives. She has been intrigued by health sciences and how the body works, so upon discovering the important role clinical laboratory scientists play in healthcare, she knew she had found her future career.

“It’s just fascinating to me how with a single drop of blood or urine you can figure out the whole puzzle and help with the treatment of a patient,” Segura says.

Now, Segura and 19 other CLS students at Texas State are getting ready to complete their last semester and enter a rigorous and demanding career field amid a pandemic.

For many laboratory scientists, being on the frontlines of the pandemic since the beginning is driving some essential workers to the point of physical and mental exhaustion.

“We’re working short-staffed and working longer hours…There are some people who work like 13 days straight,” Swink says.

With longer shifts, shorter breaks and the weight of the pandemic on their shoulders, professionals have resorted to early retirement, changing professions, quitting or transferring to higher-paying locations.

Rohde says if these trends continue, the hit to the healthcare system could be detrimental due to how heavily doctors and nurses rely on these scientists to provide accurate diagnosis and treatment plans for patients.

“I don’t want to get too dark here either, but without medical laboratory professionals to conduct these tests, far more people would die,” Rohde says.

Despite this, professionals like Swink are finding solace in knowing their work will continue to save lives beyond the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I myself, I love what I do, even though it’s super stressful, and at times like, physically demanding,” Swink says. “But I know that what we do is very important and necessary for patient care.”

As Segura and her classmates prepare to go into a demanding field under unprecedented circumstances, she says knowing they are all in this together is what keeps her motivated.

“Knowing that you are not alone pushes you and keeps you going,” Segura says. “And when someone else does not have the strength to do so, you help them move forward too.”

Categories:

Unsung heroes: How Texas State lab scientists are saving lives

Tania Zapien, Life and Arts Contributor

January 19, 2021

Texas State’s Clinical Laboratory Science cohort class of 2021 excitedly awaits graduation in hopes to serve their community as medical laboratory professionals.

0

Donate to The University Star

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover