As immigration across the United States-Mexico border has risen in recent years, there has been a rising issue in border communities: unidentified migrant deaths.

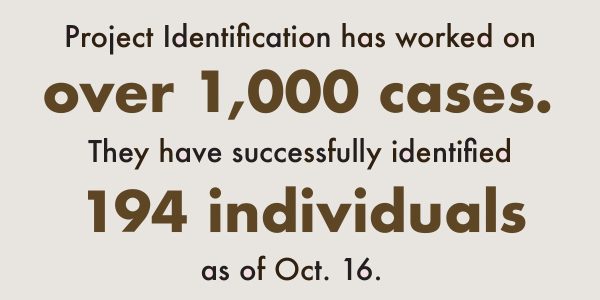

According to the Texas Department of Health Services, border communities are more likely to be impoverished, leaving them lacking the proper resources to investigate and identify deceased migrants. That’s where programs such as Operation Identification (OpID), a program run through the Texas State Anthropology Department, come in to help identify and repatriate unidentified bodies found along the border.

“I believe the number of remains we receive increases each year,” Victoria Soto, an anthropology PhD student at Texas State that works with OpID, said.

Texas has only 13 medical examiners, and among border counties, only El Paso and Webb have one. This means some affected communities do not have the resources to properly identify dead migrants.

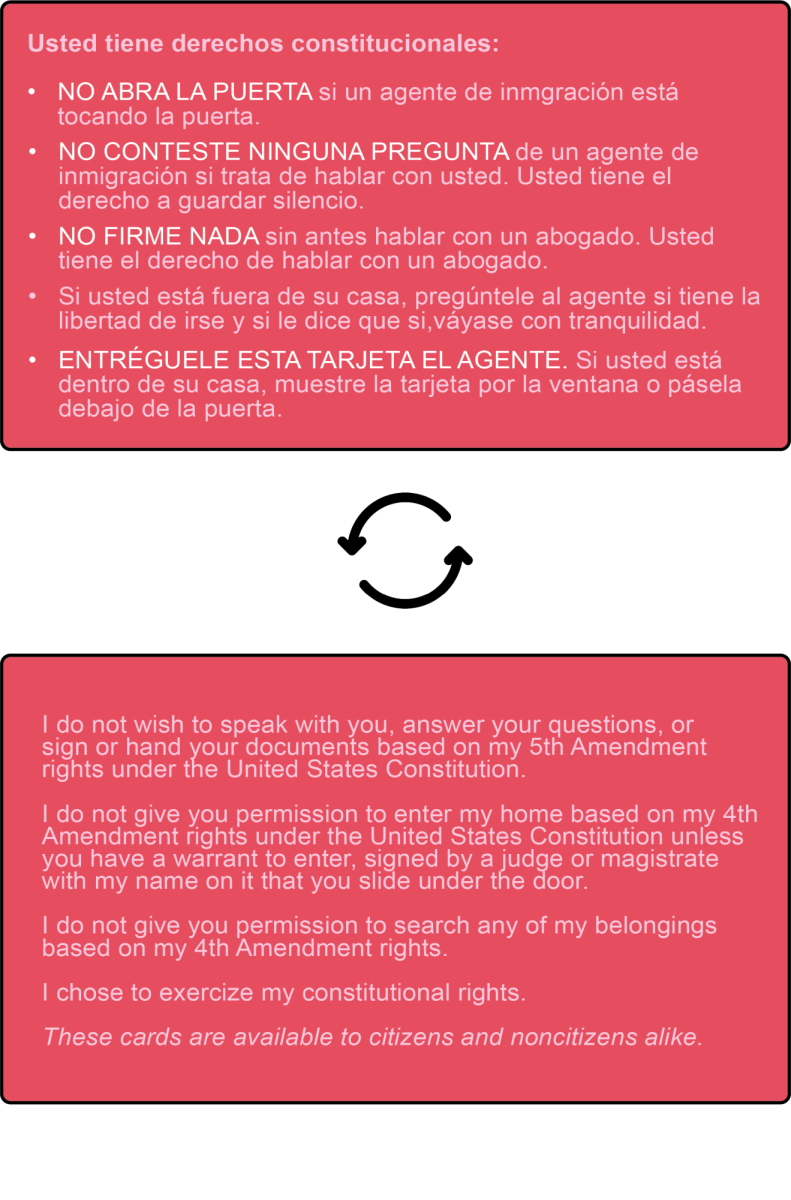

“When any individual dies and the circumstances surrounding death are unknown, the Texas Code of Criminal Procedures requires a forensic examination, collection of DNA samples and submission of paperwork to an unidentified and missing persons database,” OpID’s website stated.

Soto said an increase in resources and better collaboration with medical examiners on the border would help them identify remains quicker and easier.

For OpID the difficulty of identifying remains can vary from case to case. Some remains are brought in with an ID or are able to be identified by fingerprints or even tattoos. Other times they only have skeletal remains to work with.

“Whenever [the remains] are more fresh, or if they just were recently deceased, that gives us more avenues, such as, like I said, the tattoos, the fingerprints, personal effects as well. It just provides more avenues of identification, rather than if it was just skeletal,” Soto said.

OpID partners with other organizations, including law enforcement for their work. Law enforcement officers, such as sheriff deputies and border patrol all work to find the remains that make their way to OpID.

Brooks County Search and Recovery Deputy Don H. White works in the border region. White’s work mostly focuses on finding individuals left behind by groups crossing the border, but more often he finds their remains.

“I’ll only find four or five, maybe six, that are still alive. Everything else I find is deceased or even skeletal from several years,” White said.

According to White, migrants cross the border in groups but can get left behind due to illness, injury, dehydration or other reasons. He said the number of recently deceased individuals increases in the summer due to the heat.

“The rest of the year, mostly, what I’ll find is skeletal [remains],” White said.

According to White, crossings in his area are down, but they are increasing in other areas of the state and country.

“A lot of the traffic, apparently, has been pushed up farther west, up the coast or up the river to Del Rio, Eagle Pass, El Paso and even California. El Paso has had a dramatic increase in deaths, so has Eagle Pass,” White said.

According to Soto, the locations where migrants are crossing the border and where they are coming from have changed in recent years. She said variation adds an extra layer of difficulty to OpID’s work, as they can no longer safely assume remains they work with are from Latin American countries.

“It kind of shifts focus,” Soto said. “There’s a Syrian national and another [person] from the Ivory Coast, so it’s more just trying to have a broader view of the individuals we see as migrants.”

Once OpID identifies a migrant, they attempt to send their remains back to their families in their country of origin. According to Soto, this can be a difficult task as it requires contacting relatives in foreign countries and foreign governments do not always cooperate.

Soto said the repatriation process can also be difficult because it is expensive and families often can’t afford to have their loved one’s body sent home.

“A lot of times, family members will opt for cremation because it is cheaper. I know that to send a full body, if they are in that condition, to Mexico was like $6,000 which is a lot of money,” Soto said.

Soto said while the work can be sad, she gets a sense of fulfillment from being able to help families. White echoed the same sentiment.

“I take comfort in the fact that there are many families that don’t know who I am, will never knew who I am, will never meet me, that I’ve helped,” White said.