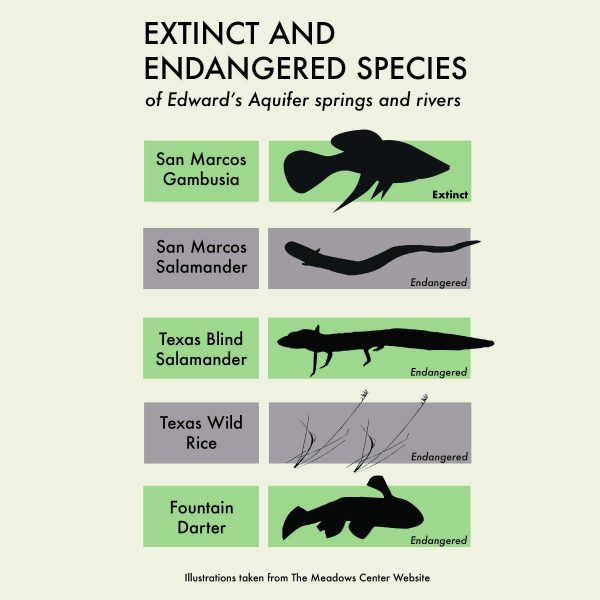

The San Marcos Gambusia was officially delisted from the Endangered Species Act by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service due to extinction on Oct. 16, with it last spotting sometime between 1983-85.

The San Marcos Gambusia was a species unique to the San Marcos Springs. The fish was first discovered in the late 1960s with a small population of 1,000. Within the next decade, there were approximately 18 of the fish left. Tim Bonner, professor of aquatic biology, said the late discovery and population decrease doesn’t make any sense with the river’s environment at the time.

“I cannot point to the extinction of any species that has happened in such a short window of time,” Bonner said. “I know about the changes in this river system, but nothing happened between the 60s and 80s that stands out as a direct link back to the extinction of this organism.”

There are still seven endangered species isolated to the Edwards Aquifer springs systems: Comal Springs Riffle Beetle, San Marcos Salamander, Texas Blind Salamander, Fountain Darter, Peck’s Cave Amphipod, Comal Springs Dryopid Beetle and Texas Wild Rice.

A majority of these species are labeled endangered because they are endemic species, which means they’re “highly evolved” to a specific location’s ecosystem.

Carrie Thompson, director of operations at the Meadows Center, said the challenge for endemic species is how dependent they are on conditions remaining stable over time.

“The species that live in the San Marcos Springs are acclimated to having relatively constant temperature and flowing spring water that’s historically been very pristine,” Thompson said.

Because of these species’ acclimation, though, the drought and even the rapid stormwater from the storms on Oct. 26, can change the conditions dramatically for these species.

The limits of an endemic species are why they’re labeled as endangered, but this doesn’t exactly mean they are completely declining.

This might be the case with the Fountain Darter, a less than an inch-long fish initially thought to only occupy the San Marcos and Comal River headwaters. A “quite abundant” population of the Fountain Darters has now been found in a part of the San Marcos River that runs through Martindale, Texas.

“If we’ve got fountain darters in the upper San Marcos River at Martindale, the San Marcos headwaters and in the Comal River, that represents three populations rather than two, and a lowered risk of extinction,” Bonner said.

While not technically listed as keystone species, the loss of each of these endangered species could either harm or be an indicator of harm in the Edwards Aquifer river systems according to Fish and Wildlife Biologist with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Services (FWS) Amelia Hunter.

“The Peck’s Cave Amphipod is the top predator among the invertebrates in the Comal Springs, and if it or any of these species disappeared, it would be a huge loss,” Hunter said.

Donelle Robinson, a Fish and Wildlife Biologist with U.S. FWS also agrees that these species would cause an impact to the aquifer’s ecosystem if they went extinct. This is in part because the Texas Wild Rice and Fountain Darter are found throughout the entire river system, despite being endangered.

Although there are some species succeeding, the threats are not diminishing. The drought is still damaging, and sometimes the recreation happening in and around the San Marcos River harms the Texas Wild Rice, causing it to need “constant management.”

“These threats include this severe drought and sediment that comes in from development in urban areas causing extreme flooding, and these can alter the habitat and change the food source,” Thompson said.

Since the passage of the Clean Water Act in 1972, Bonner said the San Marcos River has had consistently good water quality, and because of that, there’s no indication the San Marcos River’s current water quality will further impair the endangered species. However, water flow can be another threat, especially with the drought that only recently changed from Stage 4 to Stage 3.

“We have flows down at 70 cubic feet per second, and we haven’t experienced that since the 1950s,” Bonner said. “It’s usually running at around 170 cubic feet per second, so we are in new territory on the San Marcos River to see how the fountain darters and other species are going to respond to that.”

The Edwards Aquifer Habitat Conservation Plan is one reason river systems like the San Marcos and Comal rivers have maintained water quality and endangered species populations.

“These spring systems are essentially islands in the middle of Texas because they’re so different from the areas around them,” Robinson said. “The Habitat Conservation Plan keeps the river flowing by protecting the land and the species.”

Editor’s note: The print copy of this story stated that the Peck’s Cave Amphipod was located in the Comal River. The amphipod is actually found in the Comal Springs. This error has been edited.