According to an updated database from ProPublica, Texas State has the remains of 114 Native Americans in its possession as of data from Dec. 2022. Despite the university’s cooperation with Indigenous groups, the repatriation process has resulted in many of the remains remaining unclaimed.

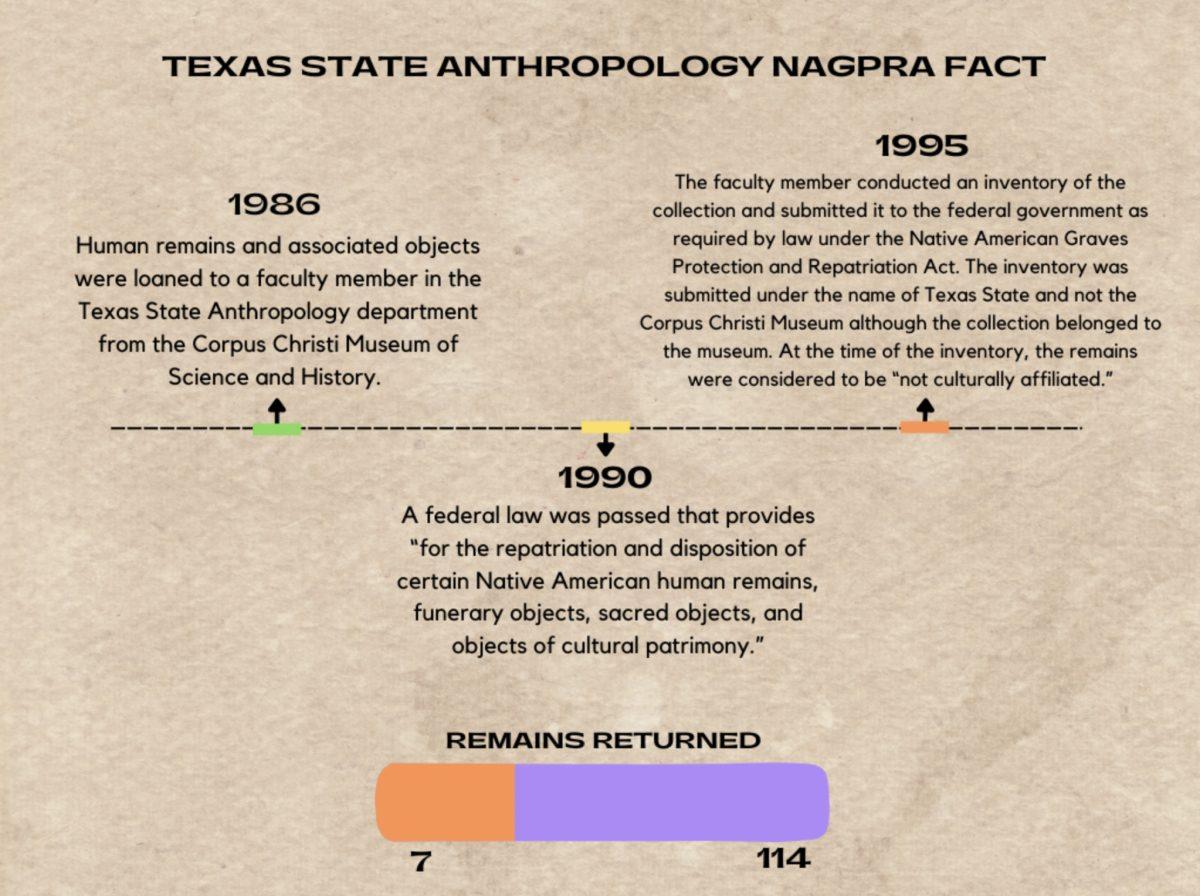

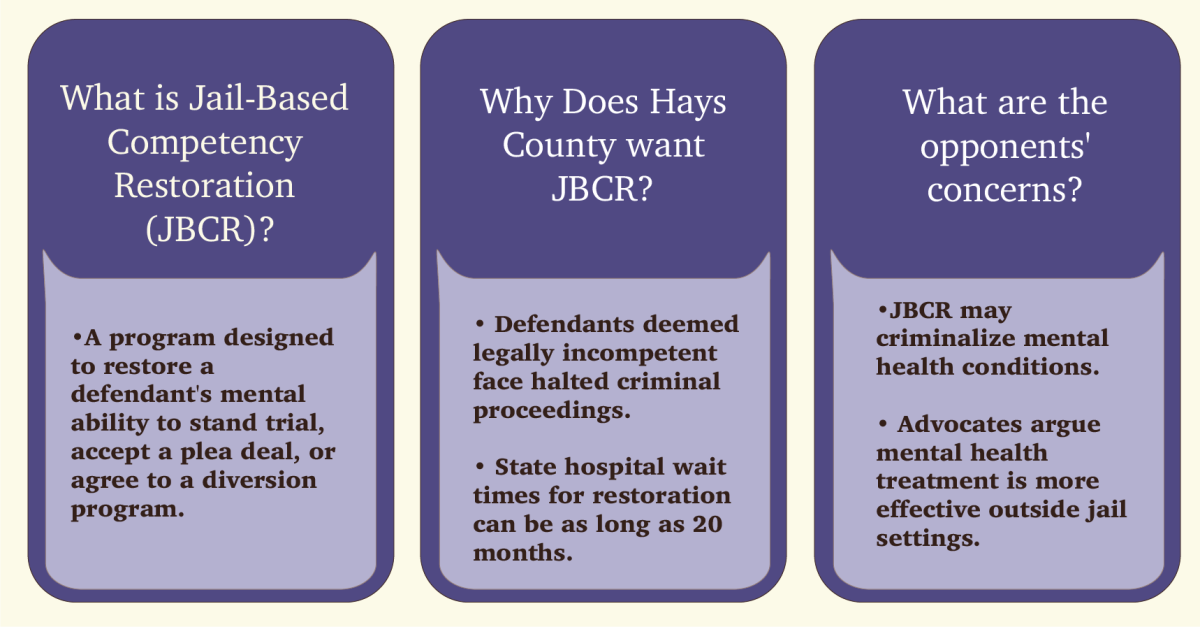

The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) is a federal law passed in 1990 that requires federal agencies and institutions to repatriate Native American remains, funerary objects and other objects of cultural patrimony.

The Texas State Department of Anthropology was given the remains that are currently in its possession in 1986 by the Corpus Christi Museum of Science and History. Five years after NAGPRA was passed, the inventory of remains was sent under the name Texas State, meaning under the law, the remains belonged to the university. The reason for this classification is unknown.

“We just know that maybe because at the time, Texas State had the remains for about nine years,” Christina Conlee, the chair of the Department of Anthropology said. “So maybe it was thought that and they did the inventory… but it’s a little unusual that it would happen that way.”

The remains of Indigenous people were also in the possession of the Texas State Center for Archaeological Studies and were uncovered in the Hays County area. These have been returned.

“Some of the remains are from campus and were excavated from campus projects and then some were excavated from Hays County and those were projects that were undertaken either by our center or Texas State University,” Todd Ahlman, director of the Center for Archaeological Studies, said.

Currently, the Department of Anthropology has 114 remains in its possession that are not available for return and the Center for Archaeological Studies had seven that were all made available for return or have been returned.

According to María Rocha, a member of the Miakan-Garza Band of the Coahuiltecan and secretary of the board of elders at the Indigenous Cultures Institute, institutions make the remains available for return by putting them into a NAGPRA database. Tribes then have to find the remains within the database.

“The institution has to have listed the remains in a NAGPRA database,” Rocha said. “So it’s up to the tribes to look up the remains.”

According to Ahlman, one set of remains was returned to the Miakan-Garza Band. The process to receive the remains, however, was long since the band is not a federally recognized tribe.

“We received a request from the Miakan-Garza Band of the Coahuiltecan and people from the Indigenous Cultures Institute and they had made a request for one set of remains that had come from campus,” Ahlman said. “So we engaged with probably about six to nine months of consultation with the federally recognized tribes.”

According to Ahlman, the other remains were made available for return but multiple groups and tribes tried to claim them. Because a decision could not be made about return, the Center for Archaeological Studies kept the remains and buried them close to where the tribes currently reside.

“Ultimately we couldn’t, between all of us, come up with a group to repatriate to and so at the advice of NAGPRA, we asked for permission to reinter those remains,” Ahlman said. “When we received permission from the secretary of interior, we did that in 2020 at the repatriation ceremony here in town.”

None of the remains at the Department of Anthropology have been made available for return. According to President Kelly Damphousse, one large reason for this is that no one is claiming the remains.

“The unfortunate part right now is that no one is claiming these remains,” Damphousse said. “As soon as we’ve got a good plan that works for everyone, we’re happy to pass it off and repatriate them to the people who want to take responsibility for them.”

The process of repatriation is complicated for the Department of Anthropology and the Center for Archaeological Studies. It involves contacting tribes and getting approvals and permissions from NAGPRA.

“There’s lists of federally and state recognized tribes and you send a sort of detailed letter that explains the situation and then what remains you have and then they can respond if they are interested in those remains,” Conlee said. “If so, there’s a long process from there and you notify the organization and there’s many steps you do from there.”

A lot of time and patience are required for the repatriation process. It can take up to years to complete. It took even longer for the remains to be sent back to the Miakan-Garza Band because there was no cemetery available to repatriate them to.

“The first set [of remains] was dug up in 2011 but they weren’t returned until about 2017,” Rocha said. “It takes a few years to get through the process right now but it took us so long because we didn’t have a cemetery available to repatriate them to.”

Another complication is that all parties have to ensure that the remains are going to the proper groups and are going to be used responsibly.

“We have to vet the people who are responsible for them and then we may actually have a ceremony of some kind to whoever receives them but only after they’ve explained what they’re going to do,” Damphousse said.

Besides the fact that time is of the essence, the university wants to ensure that the remains can be returned swiftly and responsibly.

The goal is to repatriate and return the remains to whomever they belong to and to allow the remains to rest where they need to be.

“Our goal here is to repatriate these remains and we’re working towards that,” Conlee said. “We remain in compliance with the law and we hope that we will make good progress going forward.”

Rocha feels that Texas State has been cooperative and easy to work with to achieve the goal of repatriation.

“Texas State has been the best university to collaborate with. They have been open, honest, transparent, and cooperative in their efforts to repatriate their remains,” Rocha said.

For more information on repatriation or Native American remains, visit the database.