The San Marcos Police Department is unique among most Texas police departments in its employment of a mental health unit dedicated to carrying out mental health investigations. However, the unit is small, consisting of just three officers, and officials say it needs backup.

SMPD Chief of Police Stan Standridge said he intends to implement a mental health clinician to the unit to increase its numbers and diversify its expertise. He said police officers’ job is to enforce the law, and that mental health investigations tend to fundamentally be a health crisis better suited for a professional.

“Police officers are great for establishing peace and enforcing the law,” Standridge said. “The question when we go on a mental health call is, what law has been violated?”

Due to call volume, it’s not possible for all mental health related calls to be assigned to one of the mental health unit officers. Standridge hopes the inclusion of a clinician will help increase the unit’s coverage of these dispatches.

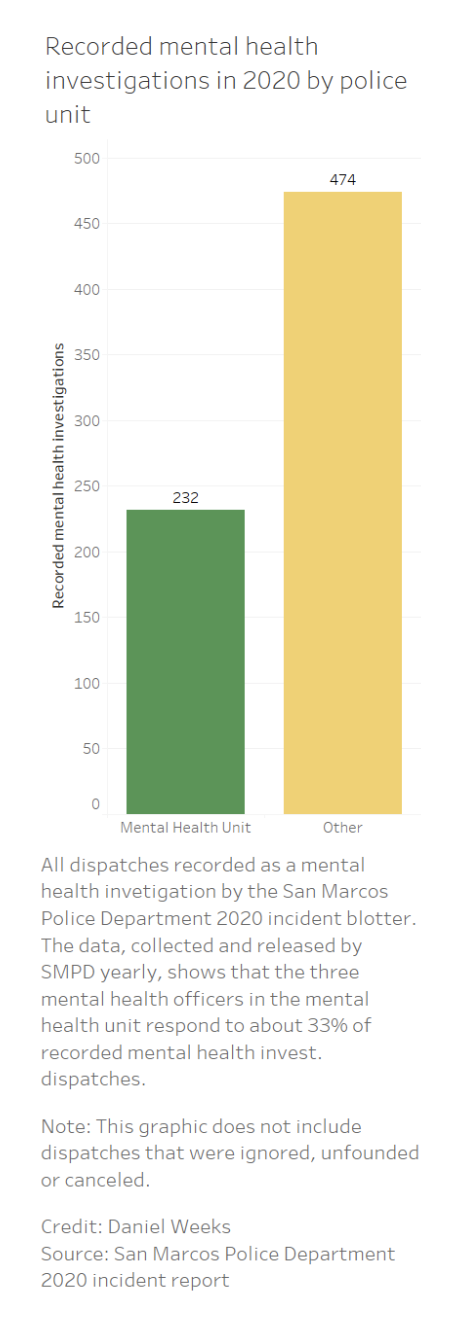

While members of the mental health unit respond to more mental health-related calls than other officers, most calls must be carried out by the rest of the department. In 2020, the three mental health unit officers were dispatched to 232 out of a total of 706 recorded mental health investigations.

The unit’s members include Cpl. Donald Lee, Officer Joyce Bender and Officer Grant Sheridan. These officers have more experience in responding to mental health crises than regular patrol officers, but all officers at SMPD receive the same basic mental health training focused on de-escalation.

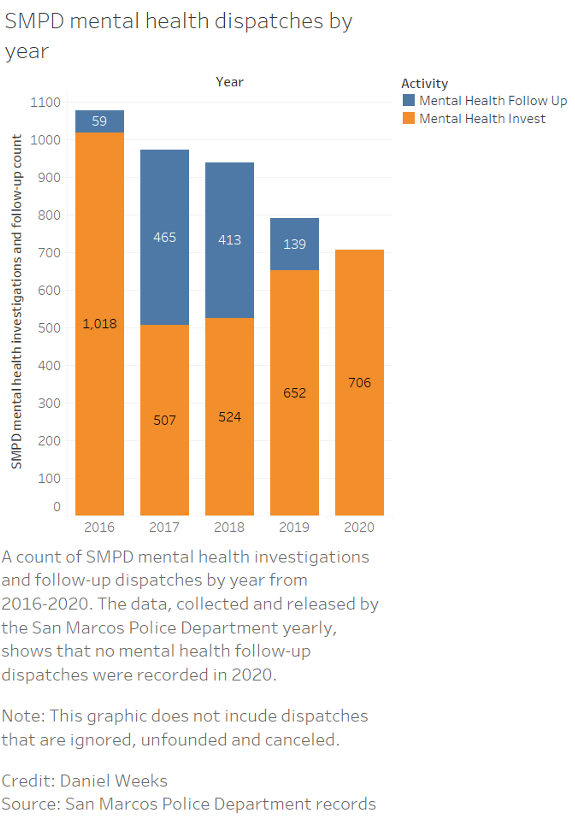

According to dispatch records published by the department each year, SMPD performed about 3,500 dispatches classified as mental health investigations from 2016 to 2020.

These investigations are similar to welfare checks: they are in response to someone calling the police due to concern for someone’s wellbeing. Officers are often sent to check on people at their homes, or sometimes they will try to call people directly.

Lee said an individual is not required to answer the door in these cases. SMPD mental health officers intentionally don’t wear full uniforms to visually separate them from police officers.

“If we come to your door, basically, it doesn’t mean you’re in trouble. Maybe we’re just checking on you,” Lee said.

Even if a potentially suicidal individual presents an imminent danger to themselves, it is protocol to not force entry into the space. In Lee’s experience, the best a mental health officer can often do is knock on the front door. In some cases, apartment complexes have more authority to enter units than the police.

“A lot of times we’re not going to be breaking the door down because there’s a lot of case law in the last years that have said kicking a door down is potentially causing a greater threat than just letting it be,” Lee said.

After a mental health investigation or similar dispatch is conducted, some cases warrant a follow-up investigation from the department. This type of investigation is uniquely proactive; they are initiated by the police department, not an outside caller.

Follow-ups are conducted after some investigations to check on the wellbeing of a person who recently experienced a crisis, such as attempted suicide, physical abuse or a mental episode, to name a few.

Since SMPD began publishing annual blotter reports in 2016, records show that the department performed about 1,080 follow-up investigations. No follow-ups appear in the 2020 report, despite all other years each having 50-400 of these investigations.

Standridge said it is possible that proactive follow-up investigations aren’t always reported due to the pace of operations, though they are happening “probably on a weekly basis.”

“The investigations are occurring,” Standridge said. “Most are reactive, in other words, they’re in response to a call. Some are proactive, where they’re actually working to prevent crisis. Not enough.”

Lee said he doesn’t have a definitive answer for why dispatch records show no follow-ups in 2020, saying that the department has always carried out follow-ups since he joined the unit in 2019. He said officers are supposed to issue an unofficial write-up on mental health investigations when a full report is not warranted.

“A lot of times, when officers go for that welfare check, or a disturbance or something like that, what they should do is they should go back in [the department’s reporting system] and they should add ‘mental health investigation’ so that we can track it better, more accurately,” Lee said. “But that doesn’t always happen.”

Standridge and Lee met in early November to discuss the issue of accurately reporting mental health calls to the annual blotter report.

“I asked my command staff [if] we have an [agency-wide] identifier, either a name or a number, that will code every mental health call,” Standridge said. “If not, why not? Because at the end of 2021, I want to know exactly how many mental health calls we went to, don’t you?”

Texas State’s Department of Sociology Chair Dr. Toni Watt, who also teaches a course on mental health called Mind and Society said that Texas is a state with particularly low spending on mental health services. A 2021 Mental Health America study measuring mental health care access in all states plus D.C. ranks Texas at the bottom: 50 out of 51.

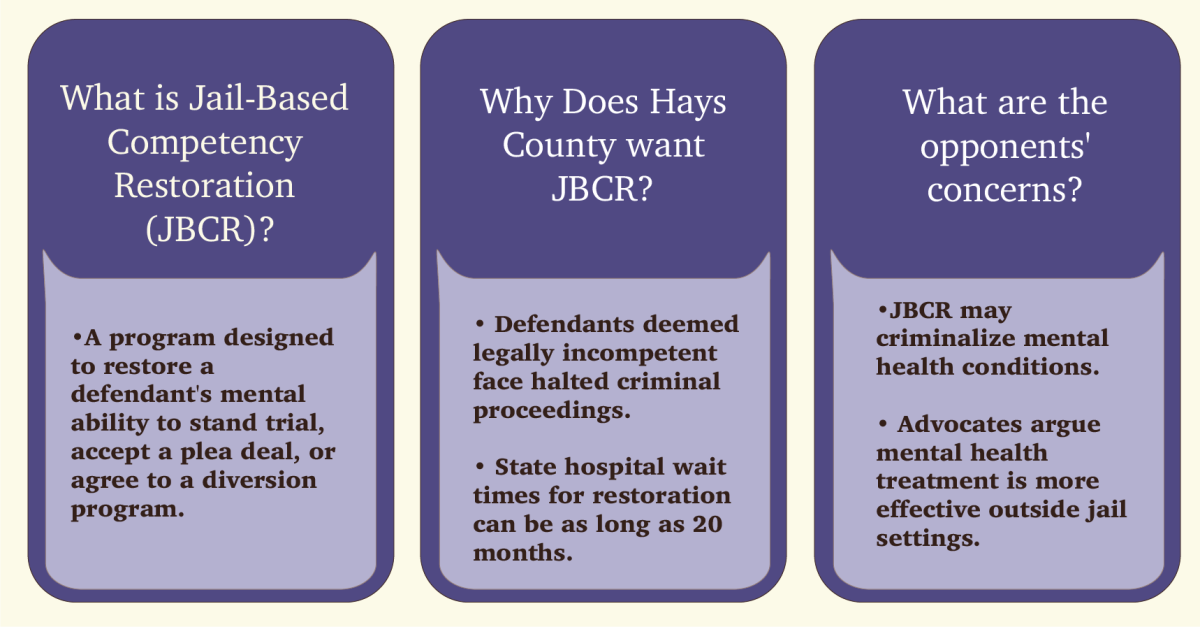

Watt said inadequate access to mental health care in the state results in people with mental health conditions disproportionately ending up in jail.

“So many calls where police are getting involved really have a need for social services and not the police,” Watt said.

Standridge estimates 40% of incarcerated persons in county jails pre- and post-adjudication have some type of mental health condition. He said there are over 1,800 people with diagnosed mental health conditions in Texas jails post-adjudication, meaning they were found guilty and await prison sentences.

“They won’t go to prison because they have a mental health diagnosis. [Over 1,800 are] waiting on a state hospital … sitting in county jails waiting for what’s called a ‘forensic bed.’ And they’re just sitting in county jail … they can’t go to a state hospital to receive psychiatric treatment because there is no better level. That’s how dire it is,” Standridge said.

Watt said that since police act as a primary response to mental health crises in Texas, having a clinician at SMPD would be “far better” than not having one. She hopes the new clinician is a licensed professional counselor or a licensed clinical social worker with a counseling degree.

“At the least, create a team where police go with someone who is equipped to address and de-escalate a mental health problem,” Watt said. “We need more training for the police. When you send a police officer, you immediately create a fearful situation, and people don’t respond well under fear.”

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, opioid overdose deaths in 2020 reached the highest number on record. In response, the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration awarded funding for states to improve mental health and substance abuse services.

A July press release from Texas Gov. Greg Abbott states, “Part of Texas’ funding, $135.6 million, is for substance use prevention and substance use disorder treatment and recovery support. The remaining $74.5 million is for community mental health services.”

Still, the $74.5 million did not appear to affect Mental Health America’s projection that Texas will rank the lowest in the country for access to mental health care in 2022. It remains to be seen where these funds will be allocated.

For additional information on MHA’s ranking guidelines and analysis on the state of mental health in the country, visit its official website.

Categories:

SMPD seeks to expand mental health unit and improve record-keeping

Daniel Weeks, News Contributor

December 29, 2021

0

Donate to The University Star

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover