From microaggressions like ignoring those with invisible illnesses when they ask for accommodations due to their higher risk of contracting COVID-19 to outright allowing people to die without medical treatment or even nutrition, medical responses to COVID-19 have knowingly left people with disabilities behind.

Michael Hickson was a 46-year-old father of five who loved his wife, his children and answering trivia questions. Hickson, who was quadriplegic and lived in a nursing facility, was taken to St. David’s with a high temperature and trouble breathing and was admitted to the intensive care unit the next day. Three days later, his wife was told he was stable and had been moved out of the ICU—but that hospice care would be calling her shortly.

Hickson was denied nutrition and hydration through his PEG tube. Five days later, he was dead, and his body was transported to a funeral home without his wife’s knowledge.

Months prior, in February, Hickson’s wife’s temporary guardianship over her husband was temporarily taken away after Hickson’s sister filed for guardianship over him at the request of a probate court investigator in Travis County.

In the meantime, a Probate Court judge ordered Hickson’s guardianship to be handed temporarily to a non-profit serving the elderly in central Texas until a hearing could be scheduled to determine his permanent guardian—the same non-profit that moved him to the care facility where he contracted COVID-19. Without Hickson’s family’s knowledge or input, that non-profit agreed with St. David’s doctors that Hickson’s nutrition and hydration could be withheld.

St. David’s released a statement July 2 claiming that “the loss of life is tragic under any circumstances,” but since they had approval from Hickson’s court-appointed guardian, they made the “difficult decision” to discontinue invasive care for Hickson. The statement has since been deleted.

People with disabilities who live in care facilities, as Hickson did, are at a far higher risk of contracting COVID-19, and thus at a far higher risk of dying. People with intellectual disabilities in New York and Pennsylvania, for example, were more than twice as likely to get sick and die from COVID-19 compared to the rest of the population.

Group homes in which many people with intellectual disabilities reside are staffed by underpaid, under-trained and under-protected workers, some of whom were not even given N-95 masks and other personal protective equipment. Those workers, coming in and out of the group homes—largely by means of public transportation—expose the residents there to infectious disease, which can be a death sentence to those who have historically fallen through the cracks of the American healthcare system.

States are codifying their disregard for the lives of people with disabilities into their COVID-19 response plans. Alabama’s plan specifically lists people with “severe mental retardation, advanced dementia or severe traumatic brain injury as those who may be “poor candidates for ventilator support.”

While Texas does not yet have a specific COVID-19 plan for those dealing with disabilities, its prior guidelines for prioritizing care and many of the guidelines used by Texas hospitals, also place people with disabilities at the bottom of the list for those who deserve life-saving measures. Additionally, Lt. Gov. Dan Patrick has made it clear he believes certain at-risk parts of the population would be willing to die to save the economy.

One of the main Republican talking points against the Affordable Care Act and other healthcare reforms has been the idea that bureaucratic “death panels” would decide who deserves to receive adequate healthcare. While these claims had absolutely no basis in reality when used in debates against those who support healthcare reforms, they strike far closer to the current state of medical care in the age of COVID-19.

Hickson was not the only person with a disability to be affected by COVID-19. This pandemic has affected people in countless ways—from those without transportation being left out of drive-up testing to deaf and blind people being left behind when medical care is carried out mainly through telemedicine.

The St. David’s Foundation, which co-owns the St. David’s HealthCare system, gave $6 million to Texas State’s St. David’s School of Nursing, earning a name on the building and an academic affiliation with the hospital group. Many Texas State students, faculty, staff and their families have disabilities or other chronic conditions that will affect their ability to return to face-to-face instruction.

While Texas State is offering its employees modifications based on medical certification of their risk, it does not appear the same accommodations are being made for students across the board; instead, it leaves their fate in the hands of the faculty teaching them.

Similarly, being a caretaker for a loved one with a disability, or working at a healthcare facility, does not seem to be a qualification for accommodations. This leaves faculty, students and staff with a choice: Get left behind or put their loved ones at a higher risk of contracting COVID-19.

We must be cognizant of how people with disabilities go ignored when we talk about allocating hospital resources, reopening schools and businesses and healthcare reform as a whole. Michael Hickson’s death is unacceptable. We should not sit back and allow this to happen to anyone else.

–Toni Mac Crossan is a biology graduate student

The University Star welcomes Letters to the Editor from its readers. All submissions are reviewed and considered by the Editor-in-Chief and Opinion Editor for publication. Not all letters are guaranteed for publication.

Opinion: COVID-19 is exposing the inherent ableism in healthcare system

August 13, 2020

By Blake Wadley

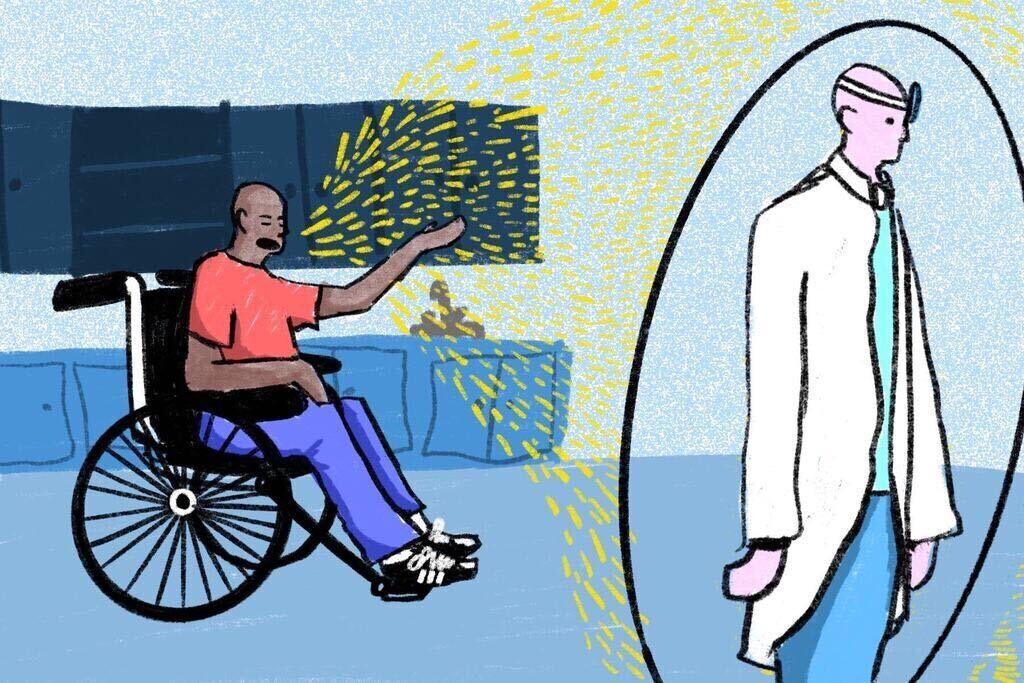

An illustration of a Black man in a wheelchair wearing a red shirt and blue jeans is ignored by his doctor. They are at the doctors office. The doctor is surrounded by a shield that allows him to remain unbothered by the man in the wheelchair.

0

Donate to The University Star

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover