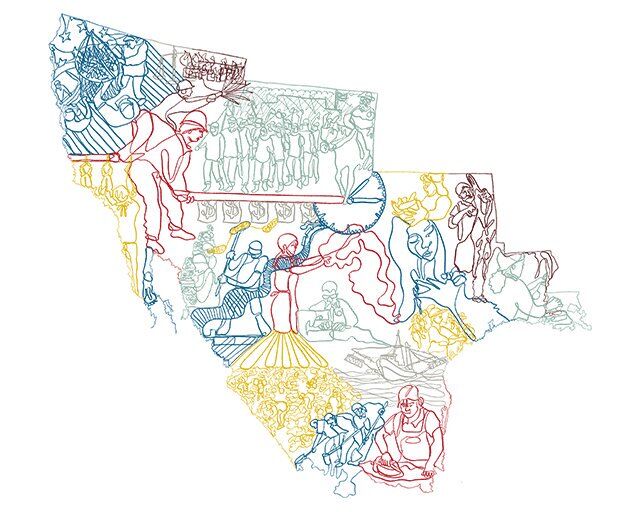

Texas State is hosting a conference titled “Chasing Slavery: The Persistence of Forced labor in the Southwest,” Oct. 25-26 in room 230 in Flowers Hall.

The conference will focus on what some activists and historians studying human exploitation consider to be modern-day slavery. Presentations and speeches will cover topics like human-trafficking, immigration labor exploitation and forced, unpaid prison labor.

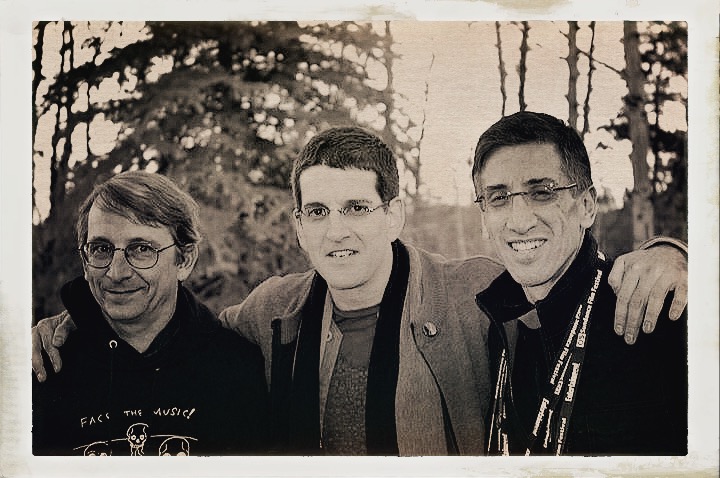

Among the presenters is keynote speaker Luis C. Debaca, former U.S. ambassador, presenting “Chasing Slavery: Reflections from the Southwest” at 7 p.m. Oct. 24 in the Alkek Teaching Theater.

Robert Chase, author of “We Are Not Slaves: State Violence, Coerced Labor, and Prisoners’ Rights in Postwar America,” and Jermaine Thibodeaux, doctoral candidate in the history department at The University of Texas, will be speaking at the conference. Chase and Thibodeaux are set to discuss the topic of forced, unpaid labor in Texas correctional facilities.

In Texas, there are about 163,000 inmates incarcerated in maximum-security prisons who work for “nothing,” Chase said.

Texas Correctional Industries, a state entity under the manufacturing, agribusiness and logistics division of the Texas Department of Criminal Justice, manufactures goods and provides services for-profit to both public and private sector institutions. The agency is able to deliver through the use of forced unpaid labor mostly concentrated in East Texas.

TCI generated $88 million in 2014 through the production and selling of prisoner-made products. Additionally, TDCJ reported TCI operated 33 facilities and made $84 million during the 2017 fiscal year.

The state entity trades with city, state and federal agencies, public and private institutions of higher education, public hospitals and political subdivisions for-profit, according to the TCI website.

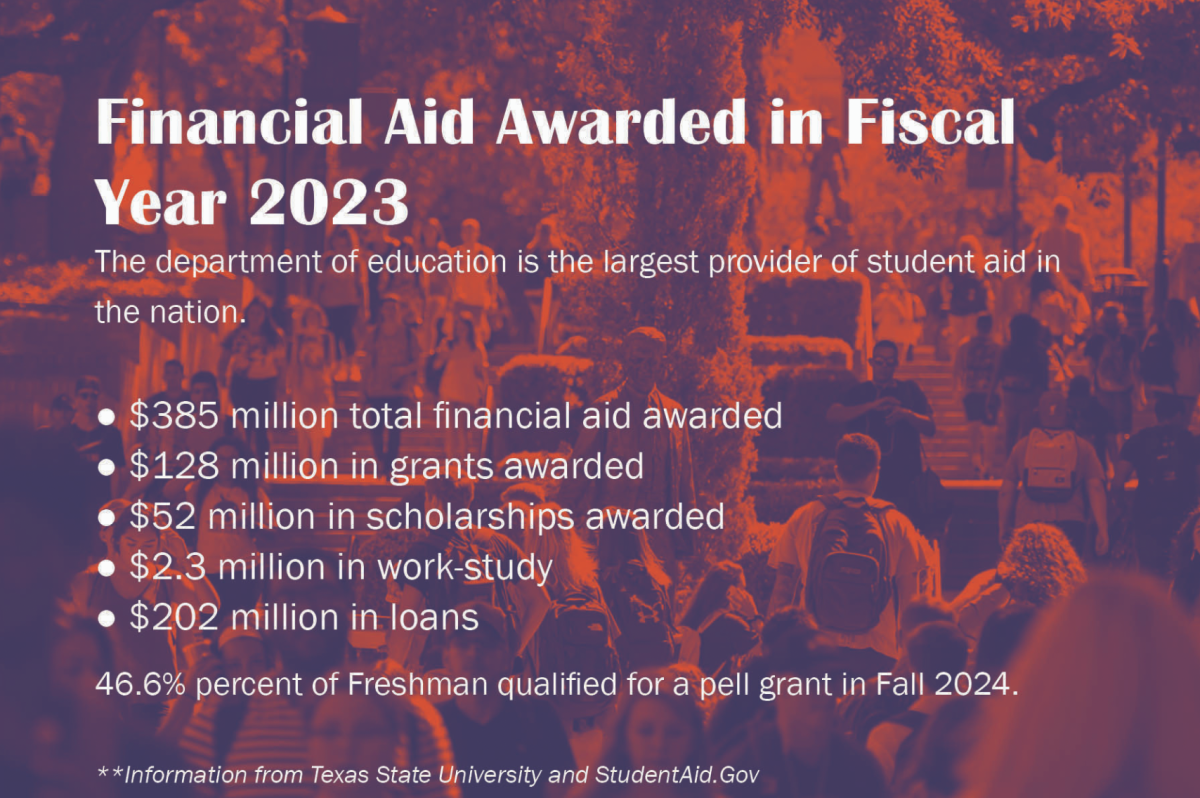

According to records obtained by The University Star, Texas State purchased from TCI twice in the past ten years, spending a total of $1,037.40 on metal street signs and lime deposit remover, according to invoices acquired via open records request.

Thibodeaux said the ratification of the 13th amendment in 1865 ended systemic slavery in the U.S. but gave rise to the exploitation of prison labor in the south.

Before the American Civil War, southern prison populations were small, majorly white and consisted of offenders convicted of felonies like murder and rape. Inmates worked to sustain their respective prisons, Thibodeaux said.

According to Thibodeaux, once the Civil War began, prisons expanded labor from sustaining facilities to crafting uniforms for the Confederacy. It was at this point some of the earliest instances of prison labor exploitation for the sake of the state arose in the U.S.

Additionally, southern states and counties began writing and enforcing “Black Codes” following 1865.

Thibodeaux said “Black Codes” acted as laws that worked to ensnare blacks into the prison system by allowing individuals to be arrested for curfew, not working or congregating in groups of three or more.

More Texas prisons started springing up at this time—the majority in the same locations where slave plantations were destroyed or abandoned because of the war.

“(The 13th Amendment) allows for those folks who have been criminally convicted to be forced into a system of free labor,” Thibodeaux said.

Texas prison population demographics switched drastically post-reconstruction from mostly white offenders convicted of violent crimes to black offenders convicted of petty offenses.

Since the system of unpaid prison labor has existed, there have been instances in which inmates exploited for their labor have gone on strike, Chase said.

There have been numerous strikes since the 1970s protesting harsh living and working conditions in prisons, like the Attica Prison Riot of 1971, the 2016 U.S. prison strike and the 2018 U.S. prison strike.

Chase said the Incarcerated Workers Organizing Committee and prisoners on strike during the 70s to present used language reminiscent to the times of slavery. Semantics are used to bring back the national sentiment toward enslavement when discussing unpaid prison labor.

Though prisoners in Texas, Alabama, Arkansas and Georgia do not get paid for their work, it is important to consider forced, unpaid prison labor historically different than slavery, Chase said.

“Legally, prisoners are not considered slaves,” Chase said. “They can file a civil rights suit, have access to property and marry—for some, even consider eventual freedom.”

Chase said prisoners call their exploitation “slavery” because, from their point of view, the experience is similar.

“(The prisoners) are engaging in entirely unpaid labor—working 10-12-hour days—making a profit for the state,” Chase said.

In Texas, the average prisoner spends about $22,000 a year while living in a state penitentiary. This is compared to California at $64,000, Alabama at $14,000 and Louisiana at $16,000.

The average national daily wage for regular prison jobs is 86 cents, meaning the majority of prisoners leave their respective penitentiary with debt post-incarceration.

Lower yearly prisoner spending among southern states is a direct result of prisoners working for little to no money.

According to the Prison Policy site, prison jobs can be broken down into four categories: regular prison jobs, work in state-owned businesses, jobs outside the facility and private businesses.

The website states regular prison jobs include custodial, maintenance, laundry, grounds keeping and food service. Other tasks fall under the category of “institutional support jobs.”

Jessica Pliley, associate professor of history and conference co-organizer, said regular prison jobs are the most common type of unpaid labor in Texas and serve to sustain prisons.

“It is being grown through prison labor, processed through prison labor and it is cooked through prison labor,” Pliley said.

The current prison labor model is efficient and effective in lowering the cost of keeping prisons afloat. However, Texas is not required to pay its prisoners for work they complete.

State-owned business work is similar to jobs at TCI, where prisoners work for the state to make a profit—usually by selling to other state entities.

Jobs outside prisons are, “work release programs, work camps, and community work centers for public and nonprofit agencies,” according to the Prison Policy website. Outside jobs are not paid in Texas and are reserved for low-risk prisoners.

Jobs in private businesses allow companies to work with state, federal, local and tribal correctional facilities through The Prison Industry Enhancement Certification Program to produce goods using prison labor.

Texas does not meet the criteria due to a lack of legislation requiring prisoners be paid for their work.

Victoria Neave, state representative for Texas House District 107, authored House Bill 3720 during the 86th legislative lesson. The bill was meant to mandate Texas to pay working inmates a minimum of $1 a day. However, the bill was left pending in the committee.

For more information on the conference, visit the Chasing Slavery Texas State page.

Categories:

Texas State to host exploited labor conference

October 25, 2019

0

Donate to The University Star

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover