Textbook access codes are the creation of an industry that does not have its main consumers, students, in mind and are a contributor to making higher education inaccessible to the average American.

Students should not have to pay to learn lessons and do homework that cannot be accessed at the end of the semester. A textbook access code is a combination of numbers and letters that can be purchased from a college bookstore, from the publisher directly or in combination with a physical or electronic textbook that allows students access to portals where they can complete homework, review class material and utilize study guides.

A 2016 study revealed that 32% of all college courses in America list textbook access codes as part of the required materials in the syllabus (that number increases to 37.5% at community colleges and decreases to 20% at private four-year universities). While there are valid arguments in favor of textbook access codes, there are few benefits to the student.

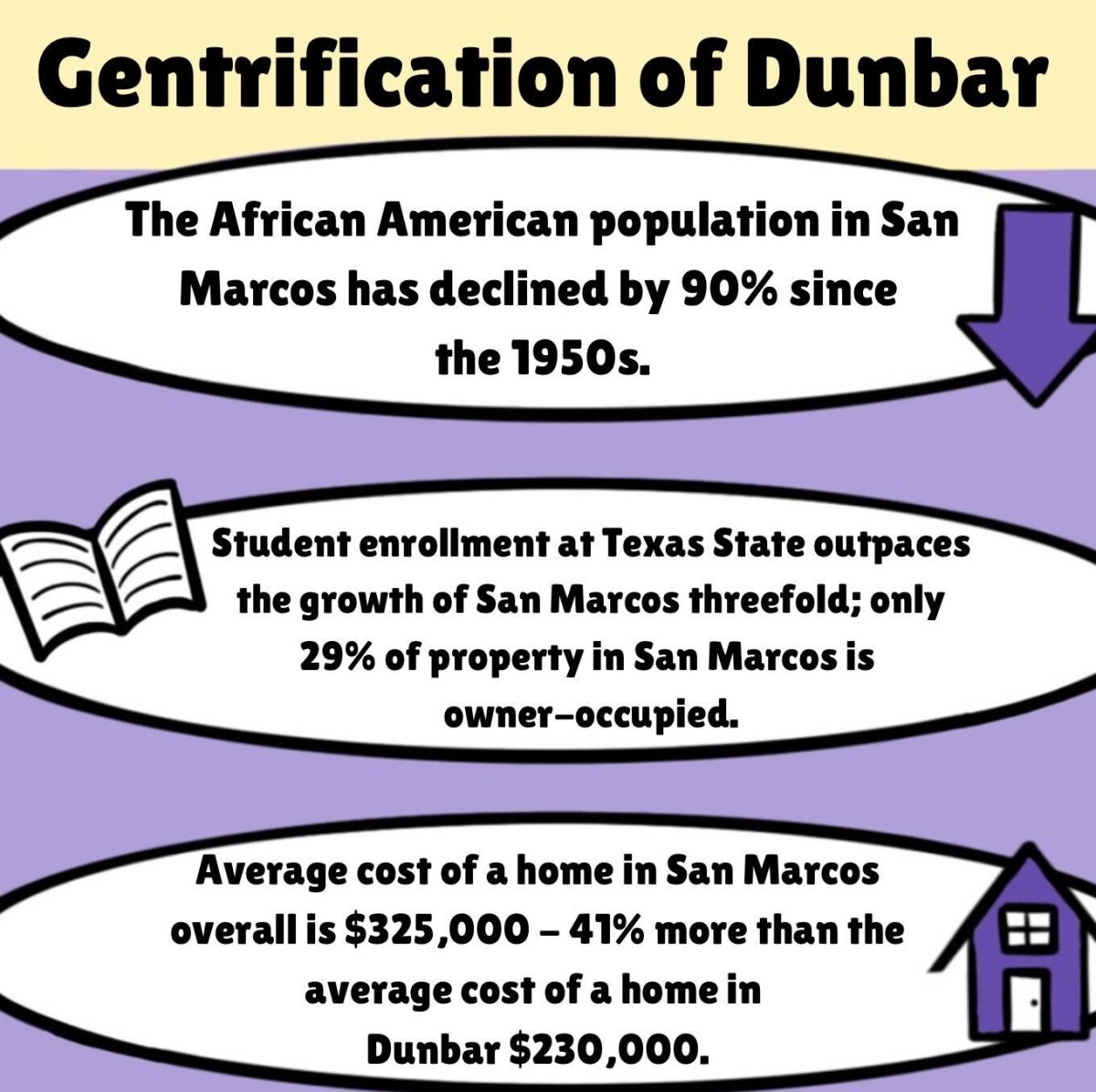

Access codes add an additional cost to the already-expensive venture of postsecondary education. According to the Education Data Initiative, the cost of textbooks increased by over 1,000% between 1977 and 2015.

The rise in costs has led to students turning toward less-than-favorable arrangements in order to afford school. This is most notable through the increase in student loan debt. Students are also turning to other sub-optimal ways to pay for college, as seen in the increase in the average amount of hours worked by students.

Studies show 63% of full-time undergraduate students and 88% of part-time undergraduate students were working over 15 to 20 hours a week in 2017. In fact, in 2016, the average number of hours worked by all working students was 28.3.

In a trend that is possibly related to the increased cost of college and the number of hours worked by students, studies have shown a steep decline throughout the decades in the amount of time college students spend studying a week. A 2010 study showed that full-time students in 1961 studied 40 hours a week, whereas full-time students in 2003 only studied for 27 hours.

Students shouldn’t have to worry about working overtime just to cover the cost of a textbook access code. Instead, they should be able to focus on their academics without the stress of needing to save money just to do their homework.

In addition, students may find themselves unable to purchase access codes without purchasing a new textbook or other materials that may not be needed. In a 2016 study, only 28% of access codes were offered in an unbundled form in bookstores, and when acquired directly from the publisher, that number only increased to 56%. Considering that campus bookstores are often the fastest and most convenient way for students to acquire books, this poses a serious issue.

Josiah Noriega, a history freshman, was caught off guard by the cost of his McGraw Hill Connect access code for a biology class when he went to the Texas State bookstore at the beginning of the semester.

“If we need them for our class, they shouldn’t be $120,” Noriega said. “I think they need to be more affordable if students want to get them from the bookstore and not on the McGraw Hill website.”

This shock was compounded due to the fact that he had previously taken a Spanish course that had included the cost of his Connect code in his tuition.

“I didn’t have to purchase [an access code] last semester because Connect was included with my tuition, so I was confused when I had to buy a code for this biology class,” Noriega said.

As students and the economy grapple with the implications of the rise in college costs and the slow decline in increased wages, the costs of access codes contribute additional financial stressors to students, especially to those who lack financial support from family or those who rely on loans to cover their expenses.

Furthermore, access codes are often designed to be temporary; students are advised to expect their code to work only for the duration of their course or, at best, for two years.

As a result, access codes require students to pay to complete homework that they cannot access after their course ends. Not only does this create a pay-for-play model, but it restricts students from revisiting old material and assignments.

Some platforms, such as McGraw Hill Connect, advise instructors to make copies of old grades before deactivating, as they are not accessible once accounts are deleted. This is a practice that deprioritizes education and learning in favor of profits for the company.

Finally, access codes further usher the college textbook industry into a monopolistic market. Access codes are, whether inadvertently or intentionally, eliminating the markets for low-cost alternatives such as renting or purchasing used textbooks.

Unfortunately, not only do monopolies stifle innovation and quality control, but they also subject students to any whim the companies have to change prices at will. In a sense, we have already headed that direction, as each new textbook edition leads to a 12% price increase, and every three or four years, a new textbook can cost 50% more than a used version.

However, the wholesale adoption of access codes will hasten and worsen the textbook monopoly. This will not only negatively impact the accessibility of higher education but will also lower the quality of information students receive.

There are some benefits of an access code. Access codes often offer automatic grading, which can be a huge benefit to professors and their graduate assistants. They also often offer accessibility through mobile apps which provides students the option of completing assignments on the go.

Noriega, despite his initial shock at the sticker price, finds some benefit to his Connect membership, citing its convenience as one of its best attributes.

“I guess what I like best about [access codes] is that they are able to let us get the book we need for our class and allow us to get our work done there since most teachers use the assignments that are in Connect as grades for their class,” Noriega said.

However, these benefits do not seem to provide students much value in the grand scheme of things, especially considering the cost of access codes, which can average as high as $1,240 a year.

In conclusion, textbook access codes create a net loss to the student and should not be normalized.

– Tiara Allen is a marketing senior.

The University Star welcomes Letters to the Editor from its readers. All submissions are reviewed and considered by the Editor-in-Chief and Opinion Editor for publication. Not all letters are guaranteed for publication.

Opinion: Textbook access codes provide few benefits, many hassles for students

Tiara Allen, Opinion Contributor

January 31, 2022

0

Donate to The University Star

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover