Sundance Apartments was contacted multiple times via phone call for this story but did not respond.

Nearly 1 million Americans are evicted each year according to national estimates—a process proven to result in severe financial, emotional and physical stress and long-term ramifications that can affect tenants’ ability to find housing again.

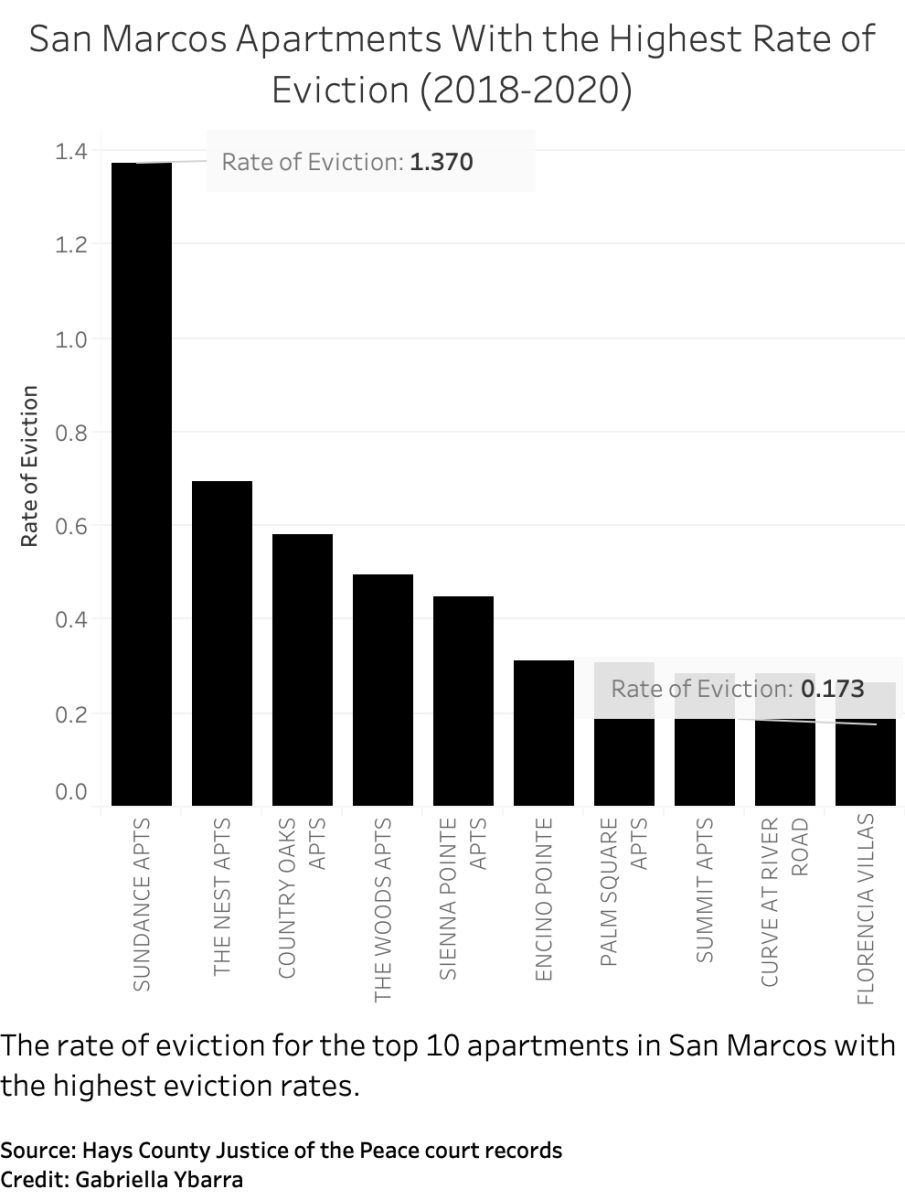

In San Marcos, 540 apartment tenants had evictions filed against them in 2018. In 2019, that number increased to 673 tenants—a 24% increase, according to Hays County Justice of the Peace court records. Prior to the pandemic, 2020 was on track for a similar increase before the U.S. government halted most evictions.

The implementation of the 120-day CARES Act eviction moratorium March 27 paused evictions in federally-subsidized housing, covering between 12.3 and 19.9 million households. After the moratorium expired in July, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) issued its own eviction moratorium Sept. 4, set to expire Dec. 31.

Sundance Apartments, a complex with eight units at 400 Linda Dr., had the highest rate of eviction from 2018-2020 with 11 evictions. The rate of eviction is determined by dividing the apartment’s total number of evictions by its number of units. When analyzed with data on apartment units and bedrooms, which was manually collected by members of a Texas State data journalism class, the rate of eviction at the apartment was found to be 1.370—a rate much higher than surrounding complexes and nearly double the rate of the second apartment with the highest rate, The Nest Apartments, at 0.696.

“The consequences are pretty dire,” Fred Fuchs, a housing attorney with RioGrande Legal Aid, said. “Many landlords will not lease to someone who has a court judgment of eviction on their record, period. [If] you’ve got a court judgment of eviction, they won’t deal with you.”

Most evictions occur when a tenant is unable to pay rent, resulting in a seven-year mark on a tenant’s record, hampering their ability to find housing in the future.

In the state of Texas, an eviction starts with a three-day notice to vacate the area given to the tenant by the landlord. The length of the notice period can differ depending on the lease. If the tenant does not vacate the property, the landlord can then file an eviction lawsuit in court. Once a lawsuit is filed, state law requires the eviction trial to be held by the justice of the peace within 21 days.

In court, the tenant can provide a defense to convince the judge they should not be evicted. Typically, the most common defense involves an improper notice to vacate, which according to state law must be delivered in person to the tenant or someone in the household who is over the age of 16.

“Oftentimes, landlords will just stick [the notice] between the door and the doorframe. That’s improper delivery of the notice, and landlords are not supposed to prevail in those kinds of cases,” Fuchs said.

While this particular defense has proven to be the most successful in court, most tenants never show up to their court hearings to tell their side of the case, resulting in a default judgment made by the court in favor of the landlord.

“It may be that they see it as hopeless,” Fuchs said. “They realize they’re behind on rent, and they look at having to go to court and weigh that against going to their job and getting paid so they can try to get the money to move elsewhere.”

Because an eviction lawsuit is a civil case handled in civil courts, tenants do not have the right to a court-appointed attorney. If a tenant cannot afford an attorney, the tenant must represent themselves, which is usually the case when a tenant chooses to appear in court. Landlords, on the other hand, are much more likely to have an attorney present.

Whether a tenant is evicted or if the case is dismissed, meaning the tenant found a way to pay the rent or moved out before the hearing, the eviction filing will remain on a tenant’s record for seven years.

Evictions are reported to tenant screening companies, which landlords, especially corporate landlords, will often refer to prior to the tenant signing a lease, making it harder for tenants to rent elsewhere. If there remains unpaid rent, it may have adverse consequences on a tenant’s credit record and prevent them from accessing some subsidized housing programs, says Rene Williams, a staff attorney with the National Housing Law Project.

“A lot of folks don’t understand the gravity of an eviction judgment against you. At least the first time, because that judgment will follow you. It’ll ruin your rental history,” Williams said.

While the CARES Act moratorium was able to save a slew of Texans facing eviction, it only applied to those living in housing benefited by federal subsidies. The CDC took a broader approach when issuing its eviction moratorium, now applying to most residential tenants in the U.S., including those living in properties not classified as subsidized.

However, while the CDC moratorium provided qualifying tenants with a bit of breathing room amid the pandemic, it does not forgive a tenant’s rent. Tenants must sign a declaration stating they have sought government assistance and are making their best effort to present timely partial payments to their landlord, meaning tenants may be building up a wall of unpaid back rent in the months the moratorium has been active.

“For someone who qualifies for the declaration, it stops their eviction, but late fees continue to accrue and as does the rent, and at Dec. 31, all that is come and due,” Fuchs said.

For this reason, Fuchs says he expects to see a surge of Texas tenants on the verge of eviction in January 2021, though tenants may be able to receive rental assistance and legal aid through the $171 million in funding Gov. Greg Abbott allocated from the CARES Act in September for the Texas Eviction Diversion Program, which, after a Texas Supreme Court order, is set to be effective in all counties beginning Jan. 1. However, how long this assistance will last is unclear, says Fuchs.

“The extent to which evictions will be avoided depends a lot on the rental assistance available and making sure that tenants are aware of this eviction protections program,” Fuchs said.

A tenant may suffer from the financial consequences of an eviction for years following its conclusion, but the emotional trauma as a result may last a lifetime.

Rachel Walker is a housing advocate for Austin Tenants’ Council, which provides education and counseling to Travis, Hays and Williamson County tenants facing eviction. Walker says many tenants who otherwise had a history of paying their rent on time, when faced with a sudden loss of income and ultimately an eviction, feel as if their positive rental history has become meaningless due to the landlord’s power to pursue an eviction lawsuit.

Walker says if the tenant does not leave the property within a specified period, a constable approved by the judge can physically remove a tenant from their home—a sometimes public event that can be traumatizing to tenants and young children.

“Someone’s stuff can be removed from the home and it’s just sitting outside; people can lose their belongings that way,” Walker said. “A lot of times this is affecting families and children so people at a very young age are having to see this happen and lose their housing.”

Tenants with an eviction on their record, struggling to find a landlord to lease to them, can face downstream consequences such as homelessness. According to a report released in August, an estimated 30-40 million people in the U.S. could face eviction by the end of 2020, forcing people to the streets.

“[An eviction] really takes a lot of options off the table, and so then where do folks go? I think that’s the largest downstream impact, is that it really limits your options and you are not able to find your next place to live,” Williams said.

In the wake of the eviction crisis, a movement for the right to legal counsel has spurred in hopes of providing tenants with legal representation in courts and balancing the power between the tenant and landlord. While it has only been implemented in the U.S. on a limited basis, Williams says it has the potential to mitigate the crisis, saving countless tenants from eviction.

“San Francisco has just adopted civil right to counsel, and I believe New York as well in eviction cases, and so that will presumably be a game changer,” Williams said.

According to the Center for American Progress, a right to legal counsel can offer secondary benefits to tenants. Attorneys can help keep eviction filings off tenants’ records, arrange for alternative housing or reduce or eliminate money owed to the landlord.

If tenants have an attorney in these cases, Fuchs says they are more likely to be aware of their rights and the types of defenses they can use to save themselves from eviction.

“They may have all kinds of defenses, even in Texas, which is a landlord-friendly state,” Fuchs said. “Generally, attorneys have been shown on a nationwide basis to make a huge difference because an attorney who is knowledgeable in that area can quickly access whether there’s a good defense or whether a tenant needs to realize that they are going to be evicted and can try to take steps to try to minimize the harm to a tenant’s record.”

While Walker says widespread access to legal counsel would be beneficial to tenants, unless they live in federally-subsidized housing where they have access to more protections, she says Texas laws still do not lean in favor of tenants.

“Even if the tenant has legal counsel, if they haven’t paid rent and can’t demonstrate that they’ve paid rent, they’re unlikely to have much success in court,” Walker said.

Hays, Travis and Williamson County tenants can receive free telephone and in-house counseling from the Austin Tenants Council. For more information, visit its counseling services webpage.

For information on COVID-19 housing resources, visit the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs website. To learn more about the eviction crisis, visit Eviction Lab’s website.

Explaining Texas’ eviction process

December 14, 2020

Donate to The University Star

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.