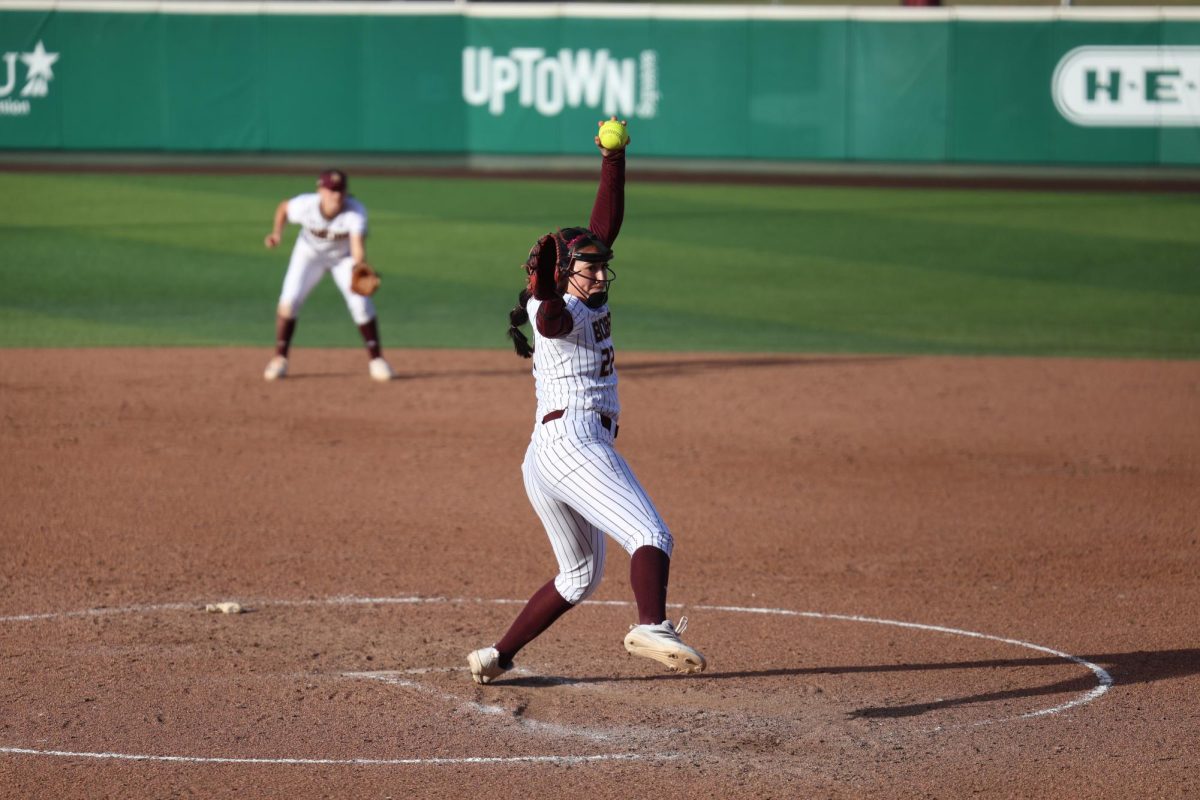

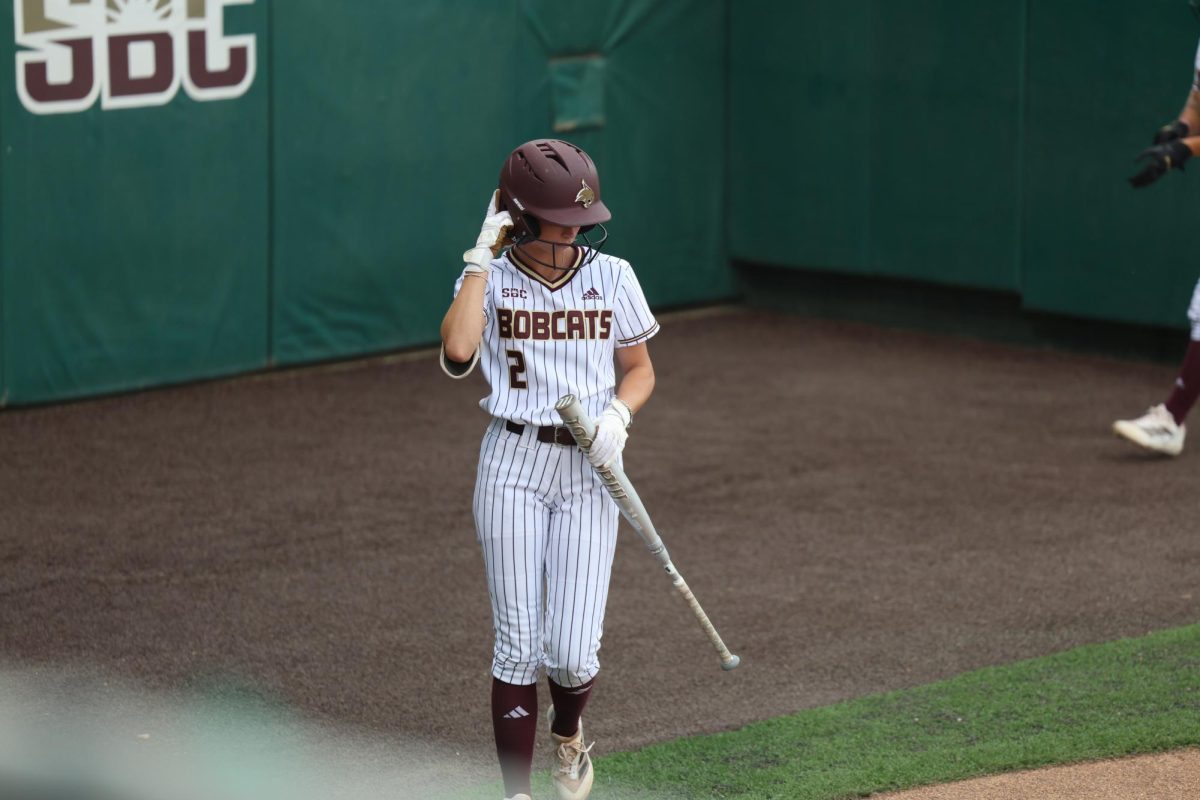

Walking into a sporting event in Strahan Coliseum, Bobcat Stadium or the Bobcat Track & Field Complex, it is normal to see Black athletes in-play, in huddles and on benches, giving fans a reason to be proud. However, for many decades past at Texas State, witnessing Black athletes and coaches on campus was not normal.

Early Black athletes at the university, dating back to 1966, arrived at a historically white institution, working to change negative narratives and stereotypes crafted in the origins of the university and country.

Black athletes and coaches faced the same prejudice, discrimination and racism those in the Civil Rights Movement were vigorously fighting against during that time period. They had to work ten times harder to be viewed as equals among their counterparts. No amount of talent or competitive success could erase the color of their skin.

While more accepted today than they were in 1966, Black athletes and coaches continue to fight against the same forces that kept their ancestors oppressed centuries before.

Dr. Johnny E. Brown, Charles Austin and Everett Withers, three Black pioneers at Texas State, all remember the good experiences they had at the university. But being on the receiving end of racism, whether blatantly or systemically, was just as, if not more, unforgettable. The three pioneers showed up to work every day and used their experiences, positive and negative, as fuel to pave the way for the generations of Black leaders to come after.

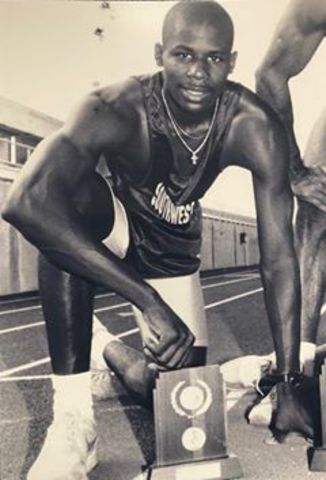

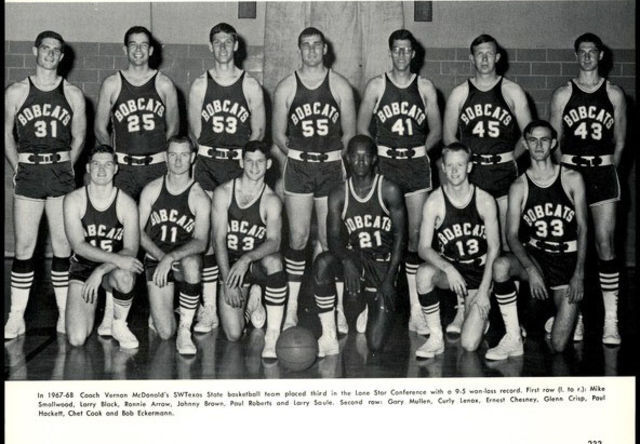

Dr. Johnny E. Brown

Johnny E. Brown, a native of Austin, was the first Black athlete to attend Southwest Texas State College. Brown attended the university from 1966-70 and played on the basketball team from 1966-68. He was never interested in being the first Black athlete at a school; he simply wanted to get an education and play basketball.

Brown, who lived separately from the rest of his counterparts in athletics, said he frequently faced discrimination based on his race but was well accepted by his peers at the school, who would often wonder about Brown’s living arrangements.

“I always felt welcomed by the other players and coaches,” Brown said. “Even when I was living in Harris Hall up top of the hill when the other athletes were living in the athletic dormitory, the athletes questioned the reason for that.”

Commonly, when Black people occupy historically white spaces, there comes the challenge of trying to fit in and adapt to the surrounding environment. While transitioning from a place where he was one of many Black people to being only one of a handful, Brown felt out of place, especially when the team would travel.

After traveling for an away game in Louisiana, people called Brown offensive and racist names—some in which he had never heard before. And in the era of Jim Crow, Black people were forbidden from various public areas and private businesses; Brown and his teammates were banned from or kicked out of places solely because he was Black.

“That experience was fairly common,” Brown said. “[I] would come in with the team, we would be standing around getting ready to eat and all of a sudden you could see some whispering going on between the coaches and the management of the restaurant, and then we would end up having to leave to go somewhere else to eat because [I was Black]. The same thing happened with some hotels as well.”

Brown went on to get his bachelor’s degree in education from Southwest Texas State in 1970 and his master’s in counseling and guidance. He then went on to get his doctorate from the University of Texas at Austin.

While Brown’s decision to come to Southwest Texas State was not based on race and equality, he said they have helped shape his life and career.

Brown decided the best way he could make a difference was through schooling, saying he strived to be “a civil rights leader through education.” Brown says he believes if children of all demographics were given equal access to education and were taught the right way, the country would be a much different place.

After experiencing success at well-funded schools, Brown and his wife left Central Texas and chose to work in areas of the country with less funding and more minority students, such as Cleveland, Ohio and Birmingham, Alabama.

Brown is now writing a book titled “The Emerson Street Story: Race, Class, Quality of Life, and Faith” about his life and experiences in his career as an educator.

Brown paved the way for future generations of Black athletes, not only with his play on the court but also his success as a scholar and contributions to underrepresented communities across the nation.

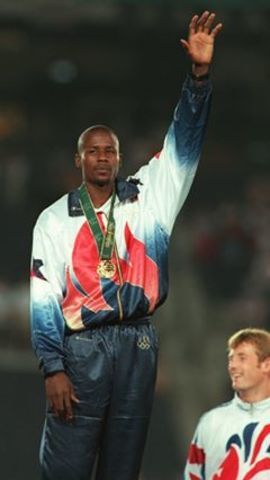

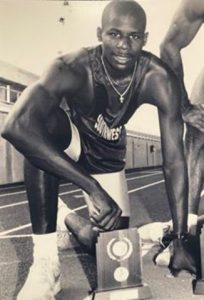

Charles Austin

Driving through San Marcos, it does not take long before one comes across Charles Austin Drive, named after one of the most iconic athletes in Texas State history—a Black athlete.

Austin graduated from Southwest Texas State in 1991 and had a successful career on the track and field team. During his career, he broke school records and won the NCAA Outdoor Championship in 1990. He was the number one college high jumper in the country.

Texas State is recognized these days for being a majority-minority institution but that was not the case when Austin attended the university. Coming from Van Vleck where he was one of many Black people, Austin was one of a few in San Marcos.

He said he once experienced racism first-hand while playing intramural basketball against a fraternity. The fraternity brothers berated Austin and his team with racist taunts and shoved him on multiple occasions.

“They called me into the intramural office, and they reported that I jumped on this guy and beat him up and did this to him and all of that,” Austin said. “I tried to tell them, I was like, ‘No, it was him’…they kicked me out of intramurals… and they let him play.”

From the 1960s to the 1990s the nation made progress toward racial equality, but it still was not enough; decades later, the same holds true.

After graduating from Southwest Texas, Austin went on to win the gold medal for the U.S. in the high jump during the 1996 Olympics, setting the Olympic record with 7′ 10″. He also invented Total Body Board and founded an athletic training company, So High Sports and Fitness.

The purpose of the Olympics is to bring together people from all over the world and celebrate similarities and differences through sports. Austin described the diversity at the Olympics as “the most peaceful experience” of his life.

“Everybody was just unbelievably cool,” Austin said. “I remember at my first Olympics we were sitting at the table with athletes from other countries… people who couldn’t speak English, we couldn’t speak their language, but for whatever reason, we were all able to communicate and really enjoyed sitting there laughing and talking.”

Austin’s name hangs in the rafters of Strahan Coliseum for his contributions to the university community. Through all of his success, he still acknowledges current conditions of the country—systemic inequality, racism and brutality—and said it will be many years before true equality is reached.

“I think we have made some steps, but there are many more to go,” Austin said. “I don’t think it’s something that’s gonna end in the next couple of months [or years]; it’s gonna take awhile. The thought process of some people is just ingrained in their heads, and it is gonna take several generations to get to weed all of that out.”

Everett Withers

Everett Withers was the first Black head coach in Texas State football history, serving from 2016 to 2018. Prior to his stint at Texas State, Withers worked at several other universities, including North Carolina and James Madison; he was also the first Black head football coach at those schools.

Some may find it surprising that a Black person had not served as head football coach at Texas State until 2016, but Withers says it was not to him. He credits this to the lack of Black people in leadership positions at institutions across the nation.

“There is not enough Black administrators; there is not enough Black presidents of universities; there is not enough Black owners of NFL teams; there is not enough Black athletic directors and quite frankly there is not enough Black alums that are capable of making decisions to hire African American coaches,” Withers said. “It’s just the fact that the people that run universities don’t look like me.”

Withers walked into a situation with the odds already stacked against him. Texas State’s football program had not witnessed much success, and its fan base was desperate to see immediate results on the field. In a country and at a university where Blackness is pressure, Withers was taking on the world.

“I knew I was not walking into a situation that was going to be smooth sailing and easy because I knew there were some barriers that were there that I was going to have to overcome—[overcome what] probably someone that looks like me would have to overcome,” Withers said. “There has got to be more African Americans willing to take those chances to take programs like Texas State football and try to make them better programs.”

Much like Austin and Brown, Withers felt accepted and loved by the Bobcat community. On at least one occasion, however, while meeting with boosters, Withers was on the receiving end of cruel and racist remarks.

“We [met] for just a coffee and a biscuit,” Withers said. “It was a couple of gentlemen that had played football…there was this one gentleman that made a statement; he said, ‘If you don’t win enough games they [should] lynch you.’”

Through the trial and tribulation—and remarks that would normally break down anyone called on to do a job—Withers worked his hardest to persevere. Although he was the first Black head coach, he said that reality was bittersweet.

“I would say it’s an honor, but it’s really a shame that in 2016 I am one of the first [Black] leaders of an athletic team at Texas State,” Withers said. “That’s really not a good thing. But it is what society is. You know there is a lot of places trying to talk about diversity, but they don’t really live it. That’s part of the problem with society now. The systemic racism in society now really, really limits opportunities for African-Americans.”