This article is co-published with The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan local newsroom that informs and engages with Texans. Sign up for The Brief weekly to get up to speed on their essential coverage of Texas issues.

The video had the feel of a public service announcement, as the two elected leaders sat around a table in Austin and discussed the importance of COVID-19 testing.

It was late March, and these men were among those tasked with organizing the response to the emerging coronavirus pandemic: Ruben Becerra, the chief executive of fast-growing Hays County, just south of Austin; and Tommy Calvert, a county commissioner representing a chunk of San Antonio, about 70 miles to the south. Also present was Becerra’s chief of staff, Alex Villalobos.

The man hovering around the officials, holding a small needle in his gloved hands, was a convicted felon turned serial entrepreneur named Kyle Hayungs. Hayungs, 37, was seeking telemedicine contracts across the state. He had no official government role, but he did have access to thousands of COVID-19 antibody tests through a company he hoped to make his partner.

“This company … is really going to help the government,” said Calvert, after Hayungs pricked the Bexar County commissioner’s finger and squeezed a drop of his blood into a test kit.

“There’s no reason we can’t roll this out to protect our people,” pronounced Becerra, the Hays County judge. “Wonderful.”

The recording ends with Hayungs urging viewers to visit two websites: one for the company selling the tests and another for a new entity he’d founded with an official-sounding name but that only a select few had heard of, CovidTaskForce.org. Meanwhile, the two masked elected officials stare into the camera.

The video, which Calvert subsequently deleted after it was uploaded onto YouTube and was obtained by ProPublica and The Texas Tribune, was perhaps the first public example of how local leaders took steps to promote Hayungs, his business interests and the antibody tests, whose accuracy has since been called into question.

Later that week, Calvert would send a memo to the court urging his fellow county commissioners to buy 10,000 of the antibody tests. Becerra would try to convince mayors in his county to buy them by the thousands.

These were the early days of the coronavirus crisis, when elected and medical officials alike were scrambling to understand how best to contain the virus and the availability of tests was limited. At the time, it wasn’t uncommon for companies to pitch their services and supplies to government officials. Companies like Hayungs’ that offered telehealth services in particular made spectacular revenue gains through the first months of the pandemic.

But what is far more unusual was for public officials to become part of the marketing effort.

A ProPublica/Tribune investigation, which included dozens of interviews and a review of hundreds of emails, audio recordings and social media posts, found the officials did not disclose to either the public or their fellow elected officials the extent of their relationships with Hayungs. The leaders worked, sometimes vigorously, to persuade their local governments to buy COVID-19 tests from a company Hayungs was hoping to partner with.

Becerra and Villalobos helped Hayungs with his proposal to advise Hays County on its coronavirus response. Villalobos edited company marketing material. And even before the onset of COVID-19, Becerra assisted Hayungs with a federal grant application and brokered a pitch meeting with the leader of a prominent local hospital.

Calvert, meanwhile, did not disclose that he once held an unpaid position on the advisory board of Hayungs’ company, MRG Medical. The pair had what Hayungs said was at least a five-year association that, according to Facebook posts, included dinners and time together at the Kentucky Derby.

The ProPublica/Tribune investigation also found a trail of misleading or false claims made by Hayungs, his employee and business associates, as well as a marketing effort that included a document apparently produced by Becerra that claimed to give an emergency use authorization to use the tests, something only the U.S. Food and Drug Administration can do.

The pandemic provided Hayungs an opportunity to achieve a goal he’d been working toward for more than a year: persuading local governments like Hays County to contract with MRG Medical for virtual care management.

The testing initiative he was promoting gave some officials pause. These entities “suddenly came into the world, and it’s the best thing since sliced bread,” said one elected official in Hays County, who — like many interviewed for this story — asked not to be identified because he feared retribution from Becerra. “We decided this was not anything we were going to invest in. It didn’t sound right, didn’t smell right, didn’t look right.”

Since early August Becerra, a Democrat, has not responded to multiple requests for an interview, written questions sent to him on three occasions or a detailed breakdown of this story’s findings. In a statement sent through a spokesman just prior to publication, Becerra said Hayungs “has turned out to be a serial exaggerator and self promoter.”

“He has never had any deal with Hays County and doesn’t represent, speak for or have the confidence of myself or the court,” he wrote. “It seems unlikely the court would ever vote to approve any contract with him.”

“I would never support non-medically credentialed AND non FDA cleared testing for our Hays County Residents,” he added. “That is grossly irresponsible and I will not be characterized as supporting any kind of effort in that capacity.”

In a written response to ProPublica and the Tribune, Calvert, a Democrat, said through an attorney that there was no conflict of interest and that he was not required by law to disclose his previous unpaid position on the MRG Medical advisory board, which he said he resigned from in December 2018. He noted that he “paid for his own trip to the Kentucky Derby … with Mr. Hayungs.”

The attorney, Pete Thompson, wrote, “At no time did Commissioner Calvert take any actions that were unethical or illegal,” adding that the commissioner “has continuously fought for better access to testing.” Thompson added that Calvert “specifically requested that the county conduct due diligence on any company considered for the testing.”

The commissioner said the video he participated in with Becerra and Hayungs was “purely educational,” adding his aim has been to secure more testing for the region. Calvert, through his attorney, emphasized that Hayungs was “in negotiation” with the company selling the COVID-19 tests and not an actual owner. “He simply assisted Commissioner Calvert because the commissioner didn’t know anything about the product or how to use it until that day,” the lawyer said.

Calvert took down the video because he did not want to appear to be officially endorsing the services and because he “observed political opponents” making an issue of it.

Calvert hasn’t fulfilled open records requests from ProPublica and the Tribune for any communication with Hayungs, citing a Texas attorney general notice that allows for the suspension of the state public information act in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Villalobos, the Hays County chief of staff, said in a statement that Republicans were blocking access to COVID-19 tests. “This was and remains a public health emergency,” he said, “and I was happy to work with any vendor who could get more of our citizens the tests they needed.”

In an interview with ProPublica and the Tribune, Hayungs said he has no personal relationship with Becerra or Calvert.

“We’re doing nothing but good. I’m open to showing my financial records and everything,” he told a reporter. But when later asked to share those records, Hayungs responded in writing, “What is the point of showing you … my financial records?”

Among the most vocal about their concerns was Becerra’s fellow commissioner on the Hays County court, Republican Walt Smith. Smith and Becerra had squared off in the past, with Smith asking the Texas Rangers last year to investigate the judge’s decision to remove an item from a court meeting agenda without the commissioners’ approval. The Rangers are the investigative arm of the state’s Department of Public Safety.

Smith had been skeptical about Becerra’s support for Hayungs since the entrepreneur had first pitched his telemedicine company to county commissioners in the summer of 2019. When he saw Hayungs was involved with the testing effort, Smith grew suspicious because of his own experience in that field: In the early 2000s, Smith worked for the chair of the U.S. House subcommittee that, in part, oversaw funding for the FDA.

“I firmly believe this is not about testing,” said Smith, who went so far as to seek copies of Becerra’s correspondence. “This is about a company who saw an opportunity to build their telemedicine business.”

The ensuing battle over the tests would consume the county’s attention at a critical time in its COVID-19 response, said another local official. By June, Hays County would become a national hot spot for coronavirus cases.

“It seemed like everyone at the county felt so burned out after” the debate over buying the kits, the official said.

Ethics experts say the failure to disclose past relationships and even the appearance of trying to steer government dollars to a specific company raises ethical and perhaps legal questions.

“There is an expectation that a government official will behave in a way that is neutral in respect to different private businesses,” said Donald Kettl, a public policy professor at the University of Texas at Austin.

“(Lack of transparency) always raises questions about why, what else is going on?” Kettl said. “Even the suspicion that something might be going on undermines the public trust.”

In his interview, and in written answers to questions, Hayungs said he believes Smith sabotaged the testing deal partly because of the commissioner’s current work as a consultant, accusing Smith of working on behalf of clients “doing testing” and of “protecting the clinics in Hays County who provide testing for a fee.” ProPublica and the Tribune could find no evidence that Smith has any current clients with a clear medical interest.

More broadly, Hayungs, Villalobos and Calvert have all argued that Smith, or Republicans in Hays County like him, are part of a broader effort they say is fueled by President Donald Trump and conservative politicians to restrict access to testing — something Smith has vehemently denied.

For his part, Hayungs said his efforts were all about business.

“It’s all networking, it’s all building relationships,” Hayungs said. “That’s what people have to do to build companies. That’s all I’m doing. There’s no bad here. Next question.”

The Origin

A December 2018 political fundraiser for Becerra on the 55th floor of an Austin luxury condo brought the two ambitious men together. A month earlier, Becerra, a businessman, had been elected Hays County judge, the first-ever Latino to hold the position there. Hayungs was a fast-talking, up-and-coming entrepreneur, who constantly worked to get into rooms with people “of (a) different caliber … in a different league,” he said during a June 2018 podcast interview, interactions he regularly posted on social media.

Becerra told Hayungs that night that he wanted to revamp the indigent health care program for Hays County residents who don’t have insurance and don’t qualify for Medicare or Medicaid. “I literally got goosebumps,” Hayungs said in the interview with ProPublica and the Tribune. His company, MRG Medical, aimed to lower health care costs through the use of telemedicine. “I almost started crying.”

The men shared common ground. Both left the Rio Grande Valley on the Texas-Mexico border in search of something bigger. Becerra and his wife, Monica, moved to San Marcos, the Hays County seat, in 2000 and bought Gil’s Broiler, the city’s oldest restaurant. He twice ran for local office and lost. He joined civic boards connected to the Latino community, including one with Villalobos, his future chief of staff, who was a law enforcement officer at Texas State University.

Hayungs took a more circuitous route. In a 2019 podcast interview, Hayungs said he “went to county jail” 17 times when he was young, the result of what he called “youthful indiscretions.” He moved to Austin for school but was arrested again in February 2008. He eventually pleaded guilty to charges of money laundering and conspiracy to distribute less than 50 kilograms of marijuana. Hayungs said in a podcast interview that he spent 18 months in a medium-security prison, finishing his bachelor’s in business administration while behind bars.

He got out in 2010 and got into merchant services and credit card processing. He launched an ATM business. Within a few years, Hayungs was a guest on podcasts seemingly aimed at other would-be entrepreneurs, shows with names like “Cashflow Ninja” and “Beta2Boss.” He talked about his connections, his earnings and the ways he’d learned to generate passive income, money that comes with minimal time invested. He framed his career as an example of overcoming the adversity of his incarceration. “Started from the bottom and now I’m here!” he told another podcast host.

Since high school, Hayungs said he also had a vision of getting into the health field and started to turn his attention to that industry. In a 2017 podcast interview, he said he was starting to focus “on something in the health care space.”

That same year, Becerra launched his third campaign for public office, as a Democrat running for Hays County judge in what would be a bruising race, with news reports detailing the Becerras’ history of financial troubles, including tens of thousands of dollars in state and federal tax liens. Becerra won, despite the controversy and his opponent’s considerable war chest.

Less than a month after first meeting Hayungs, Becerra was sworn into office on Jan. 2. At his side was his new chief of staff, Villalobos, who by then was a councilman in the Hays County city of Kyle. Smith, 45, also won a seat on the commissioners court in 2018, in his first run for office, joining Becerra. In Texas, a commissioners court handles a county’s general business, much like a city council for a municipality. Each county elects a presiding officer, known as a county judge, and four commissioners.

A week later, the judge met with Hayungs in his office, according to the judge’s calendar, obtained through an open records request.

“Maki’n MOVES in Hays County!” Hayungs wrote that day in a Facebook post, including a photo with Becerra. “Approved to Re-Vamp / Re-Brand Hays County Indigent Healthcare Program.”

The county commissioners had not approved him to do anything.

Emails over the next several months show how Becerra and Villalobos continued to help the entrepreneur. Becerra assisted him with what Hayungs said in an email was a $9.6 million federal grant application for rural health that he said would benefit Hays County. When Hayungs asked for help applying for the grant, he supplied Becerra and Villalobos with a prewritten letter of recommendation. Becerra sent it back, copied and pasted onto county letterhead. When Hayungs sent a list of county officials he wanted to meet with, Villalobos tried to help set up the conversations.

“Sorry for delayed response,” Villalobos wrote Hayungs on Feb. 6, 2019. “I am working on getting the group that you advised we needed. The scheduling part is taking some time. I am confident we can get everyone in on the same day. I will keep you updated.”

In an emailed response to questions from ProPublica and the Tribune, Villalobos said “it is typical that vendors who desire to work with the county will request the county judge and/or commissioners to meet with them in preliminary phase of introduction.”

No Hays County policies specifically prohibit a department head or elected official from communicating with potential vendors, though “statutory regulations regarding conflict could come into play,” said Vickie G. Dorsett, Hays’ first assistant county auditor.

Becerra even made a direct case for Hayungs’ telehealth services to Anthony Stahl, the president and CEO of what was then called the Central Texas Medical Center. Hays County has a contract with the hospital to provide the county’s indigent care.

“Had lunch with CEO of hospital today,” Becerra wrote in a March 21, 2019, email, whose recipients included Hayungs, Villalobos and Calvert, the Bexar County commissioner. “He’s excited. We need to schedule a meeting with all parties to be effected for maximum buy in.”

Stahl describes his reaction differently.

“I would not characterize it as excited at all,” said Stahl, now president of Adventist HealthCare White Oak Medical Center in Maryland. No one in the county’s indigent health care program was looking to revamp the system or to invest in telehealth at the time, he said.

But Stahl wanted to be a good partner and agreed to a meeting. When hospital officials asked if they could visit one of the sites where MRG’s technology was already in use, Stahl said he can’t recall ever hearing back from the company about a location.

Hayungs finally got his chance to pitch the Hays County commissioners at a public meeting on June 25, 2019. He said his company’s services, which included remote patient monitoring, could ultimately reduce the county’s indigent care costs. Commissioners and a county health employee expressed confusion about what exactly Hayungs wanted to sell them or how it would benefit the county.

“It was just very odd,” said Smith, who did not attend the meeting but later watched the video. The item was labeled as part of a workshop on virtual care, but Hayungs’ company was the only presenter. He also cited contracts and connections with the University of Houston and the Texas Organization of Rural & Community Hospitals, known as TORCH. ProPublica and the Tribune contacted the organizations, who said no such contracts exist, though he met with officials at both.

“We’re just looking for an opportunity to put Hays County on a national map and use it as a model to do this across the country,” Hayungs said in commissioners court that day, adding, “I want to start at the county level, then we come out on the news and then every primary care in the area is going to be calling us.”

MRG’s technology was “light years ahead of everybody that’s in the market,” he told commissioners.

During the meeting, a Hays County Health Department official expressed concern about Hayungs’ plan, deeming it impractical for the population the office serves. Hayungs kept telling county officials that Medicare and Medicaid would pay for the service, but indigent care clients aren’t covered by either. Most of her clients needed help filling out forms or couldn’t read, she said. Some were likely to pawn a fancy device like the medical grade watch MRG offered.

Hayungs’ dream for a deal went nowhere. That didn’t end Becerra and Hayungs’ relationship.

In September, Hayungs posted a photo on Facebook of himself at dinner in Austin with Becerra and his wife, as well as Villalobos and Calvert. Both Becerra and Villalobos would attend a meeting with Hayungs at the University of Texas at Austin’s Dell Medical School, another instance in which the entrepreneur afterward claimed a partnership on Facebook. Dell said in a statement it has never had a business relationship with MRG.

Hayungs would also take to Facebook to express support for Villalobos’ bid for county sheriff in the November 2020 election. Hayungs said that he provided Villalobos “a roadmap to use as a strategy” for his campaign, adding: “I did the work pro bono and have not contributed in any other way to (Villalobos) or his campaign.”

Villalobos said the help consisted of Hayungs’ “hot take on social media while we were waiting for a meeting to start.”

Hayungs was always selling. In October, he was spotted with Becerra during a county government conference in Galveston, where two county commissioners from Calhoun County, interviewed by ProPublica and the Tribune, said they briefly spoke to Hayungs. Hayungs was a “typical salesman,” recalled Calhoun County Commissioner Vern Lyssy. “I can’t remember exactly what his sales pitch was, but he could get people these watches and these watches would determine if you’re going to be sick or not and it would save a bunch.” Lyssy’s wife kept kicking him under the table, he said, trying to get him to stop the conversation.

Both Lyssy and his fellow county commissioner, David Hall, separately recall Hayungs talking about keeping any potential contracts under $50,000, so they wouldn’t have to go out for bid.

Hayungs said he and Becerra ran into each other at the event, which vendors regularly attend. He said his focus was to ensure deals can “move quick” without officials having to “write big checks.” (In Hays County, contracts below $50,000 do not have to go out for competitive bidding.)

To the two Calhoun County commissioners, the behavior was striking. “That’s a red flag,” Lyssy said.

Hall agreed. “Once I heard that, it was like, dude, you’re going to end up in prison.”

The COVID-19 Opportunity

Toward the end of March, Hoppy Haden, the chief executive of rural Caldwell County, southeast of Hays, received an email pitching COVID-19-related telehealth services. Like many Texas elected officials at the time, Haden was receiving a deluge of offers from medical and supply companies, selling masks, gloves, tests and health care solutions.

He deleted most without a second thought. However, this email, from a company called MRG Medical, caught his eye. “We are the FEMA designated Covid response team for Hays County,” the email claimed, “and will soon likely also be for Harris, Bexar, Uvalde, Williamson and Travis Counties.”

The email sounded official, but something felt off. Haden forwarded it to his regional Homeland Security director, who in turn sent it to a contact of his at Hays County.

“Are these guys legit?”

“Yes, they are,” responded Villalobos, the Hays County chief of staff.

The email was part of Hayungs’ latest venture, an effort to sell telehealth services to Hays and other counties, but this time using the COVID-19 pandemic to do so.

In reality, Hayungs and MRG Medical had no official role with Hays County or with any of the other counties mentioned. FEMA has told ProPublica and the Tribune this characterization is “misleading and inaccurate.”

But on multiple occasions, Hayungs and his associates would invoke the county and Becerra’s names to try and win COVID-19-related contracts across the state.

By March, Hayungs had developed relationships with two companies based in the Austin-area: AnyPlace MD, which provides care to the military and in places like prisons and nursing homes, and Reliant Immune Diagnostics, led by a Berkeley and Columbia-educated doctor named Henry Legere.

Before the pandemic, Legere had developed a mobile app called MD Box to help people track their symptoms for ailments like strep throat and urinary tract infections and access diagnostic tests. With the arrival of the novel coronavirus, MD Box added COVID-19 testing to its portfolio, acquiring a large quantity of antibody tests manufactured by a company in Guangzhou, China, called Wondfo Biotech.

At the time, much confusion surrounded antibody tests, and the Wondfo tests would prove particularly problematic. Unlike molecular and antigen diagnostic tests, the FDA warned that blood-based antibody tests were not intended to diagnose an active infection but rather reveal if someone previously had the virus. Nearly all antibody tests existed in a confusing gray zone of regulation.

At the beginning of the pandemic, the FDA took the unprecedented step of allowing companies like Legere’s to distribute antibody tests that were not authorized by the agency. Wondfo was one such test that the FDA hadn’t yet vetted but that vendors could sell.

Becerra announced his intention to buy 2,000 of the tests. The cost was $39,000, according to an invoice obtained by ProPublica and the Tribune. He did so without input from key Hays County medical leaders or approval from his fellow commissioners, as county rules require.

Emails obtained through the Texas Public Information Act show that Becerra and Villalobos also had been conferring with MRG about the company’s proposal to advise the county on its COVID-19 response and conduct a health assessment to measure the county’s “preparedness.” The proposal called on the county to “activate private sector supporters.” Villalobos went so far as to edit the proposal, emails show.

Villalobos said in a written response to questions that any edits he made to any documents were minor and done at the direction of “a court member.”

Becerra pushed the narrative that antibody tests were preferable to diagnostic swab tests, which his office said in an April 6 press release “often provokes an involuntary coughing/sneezing/spitting episode from the patient and places those providers at great risk of contracting the virus themselves.”

The county judge appears to have issued what is called an emergency use authorization, or EUA, for the antibody tests, according to pitch materials sent to Harris County Public Health and the city of San Marcos. An EUA signals the FDA has actually vetted a test to some extent. However, the FDA has never issued such an authorization for the Wondfo tests and told ProPublica and the Tribune that a county judge cannot do so.

Hays County General Counsel Mark Kennedy concurred. “I have found no evidence in the law that says a county judge in Texas can issue an EUA,” Kennedy said.

Becerra has not answered questions about the authorization letters, which bears his signature and appear on his letterhead.

The marketing effort was rife with other claims about nonexistent partnerships with other entities and confusing messaging around the tests, which required residents to sign up with MD Box’s telehealth app to access the tests. Some local officials worried that would effectively turn test-seekers into clients of the company and subject them to a range of fees. According to the MD Box website, a telemedicine visit costs $49.95.

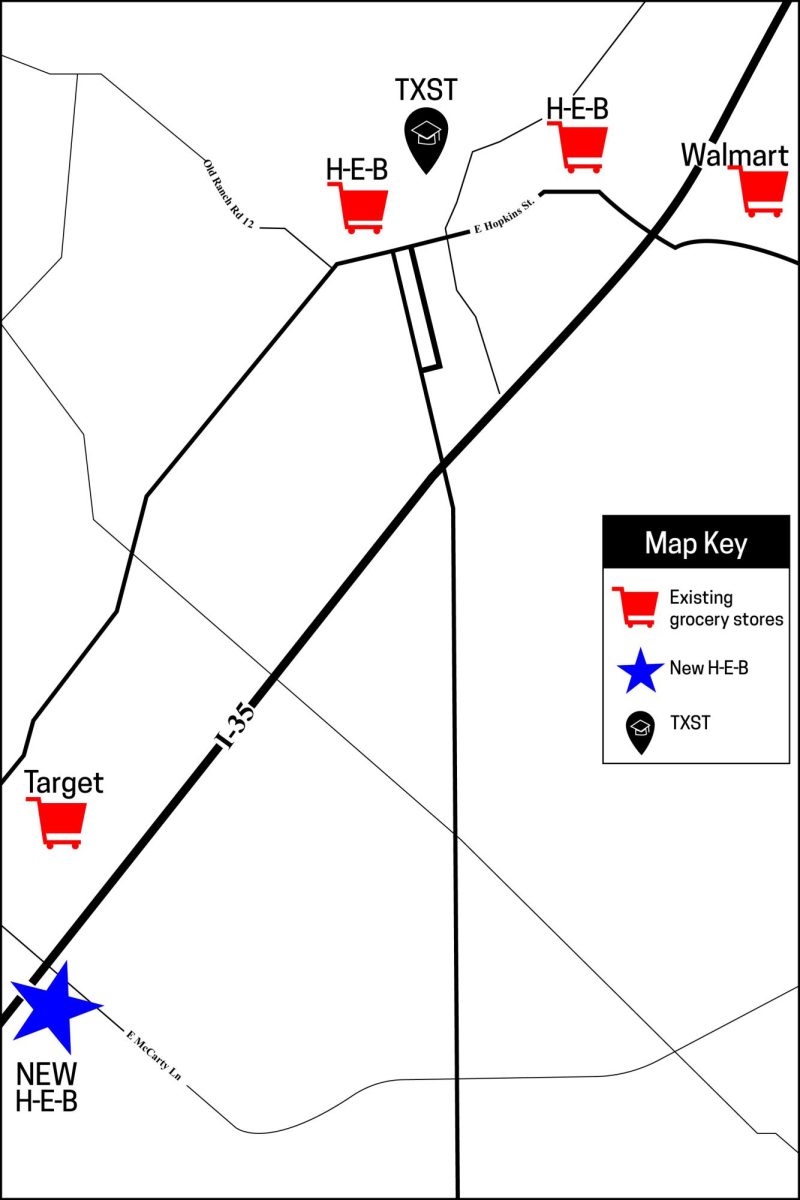

Marketing materials also claimed the tests could be taken at home and purchased online at H-E-B, a popular Texas grocery store chain. Neither claim was true.

On March 30, MRG Medical sent out a press release announcing the formation of something called the “COVID Task Force Initiative” that would bring 50,000 test kits to Hays County and praising Becerra for “lifting the FDA ban to release the test.”

“I didn’t realize I was a pioneer,” Becerra said at the press conference announcing the partnership. “It will be very easy for me to share with (officials in other counties) the clear concise road maps they would need to follow for them to emulate what we’re doing in Hays County.”

The announcement blindsided other county officials and staff.

“I will not be a party to sending out this advertisement posing as an FAQ for something not approved by the Commissioners Court or the General Counsel’s Office,” wrote then Hays County communications manager Laureen Chernow in an email to the county’s Health Department. “I just gave it a quick read and have no medical training but I am horrified by the process, the cost, and the skeezy FDA ‘approval’ disclaimer, among other things.”

Becerra would apologize for not notifying staff and fellow commissioners about the potential deal, but he said he didn’t want to announce the deal before it was finalized.

Even one of the public relations officials working on the testing effort with MRG raised concerns about the use of the COVID Task Force as a name because it could be confused with the national COVID-19 task force led in part by a federal health official with Texas roots. “I’m not sure why there would be a conflict of interest,” Hayungs responded to the PR person’s email. “The way I look at it is that gentleman will probably be adopting our solutions very soon.”

Villalobos, in his written response to ProPublica and the Tribune, said Hayungs is clearly “an aggressive salesman and may have gotten over his skis in some of his communications outside Hays County, none of which I approved.”

Smith, the Hays County commissioner, said he became suspicious of the claim of in-home testing and the nebulous boasts of FDA clearance. He sought clarification from H-E-B, which confirmed it had once explored a pilot program to sell other MD Box tests but denied it had a deal to sell the COVID-19 tests.

“We had companies that were operating, telling people they were an arm of our county government,” Smith said in an interview. “And no one in our county government knew them except for two individuals,” referring to Becerra and Villalobos.

At a contentious commissioners court meeting on March 31, Smith and Becerra traded claims of criminality. Becerra said Smith’s meddling compromised the deal. Smith accused Becerra of playing games with the health of Hays County residents.

The court did not vote on Becerra’s proposed purchase of 2,000 tests, but Becerra did not stop trying to sell them to other local leaders.

The Sales Pitch

On April 2, Becerra invited Legere, whose company Reliant Immune Diagnostics had developed the MD Box app, to a conference call with local EMS medical directors and for more than an hour tried to convince them to give their stamp of approval to the MD Box testing proposal, according to a recording of the call obtained by ProPublica. Legere emphasized he was not endorsing one test over another. “We’re a medical solution and not a testing solution,” he told them. “We use all the tests and tools available to us as any doctor would in the hospital.”

But the medical officials stood firm. “I’m concerned that the general public may take a negative result (of an antibody test) and say: ‘I don’t have COVID everything’s great. I can go out into the grocery stores or whatnot,’” Kate Remick, medical director for the San Marcos EMS, told Legere and Becerra, according to the recording.

Steven Moore, medical director of the Wimberley EMS, was blunt: “You’ve got three medical directors that don’t support this.”

Becerra continued to question their objections. “I’m sorry if I would disagree with an MD,” he said. “I don’t know what kind of MDs you are … but I’m having a hard time understanding why this is a problem to test more people.”

Hayungs said in an interview that the officials should have jumped at the opportunity.

“We were one of the first companies in the U.S. to get these tests,” Hayungs said. “OK, there’s some risk and liability, but during the pandemic when it’s a crisis and people are dying, like who cares, if they take the test and it doesn’t work it’s better than not doing anything especially when they really don’t cost anything and the government will pay for them.”

On separate conference calls with mayors and other elected leaders in Hays County, Becerra urged his fellow leaders to buy thousands of the tests and claimed they were more than 90% accurate. In fact, at least one study showed the Wondfo tests were only about 55% accurate when performed as a finger pinprick blood test.

Becerra also gave them shifting, often conflicting, information regarding the FDA emergency use authorization, which the tests still lacked despite the judge’s apparent homemade order.

When the mayor of San Marcos asked if the test had an emergency use authorization, Becerra responded: “Yes, I think they already have that. That’s exactly what allows them to do what they are doing.”

Though Hays County emergency medical directors had said they opposed purchasing the tests, Becerra continued to tell other leaders they had “an interest” in the testing.

Even as he told local leaders that he didn’t specifically endorse MD Box, telling them he wasn’t trying to pick “winners and losers,” he emphasized on a later call he thought its tests were a “great tool.”

“We as the government can buy this test for our vulnerable population,” he said, adding: “We can make that decision. We are all on the phone right here.”

Local officials and emergency responders began doing their own research into MD Box and the Wondfo tests.

Bill Foulds Jr., the mayor of the Hays County city of Dripping Springs, said his city was concerned about the lack of clear costs associated with the telehealth aspect of the test and accompanying app, as well as the tests’ effectiveness. “We never felt these tests offered quality results or had a success rate and dependability that we would feel confident that we were going to stop the spread of COVID-19,” he said in an interview.

On April 5, Hays County EMS medical directors issued a lengthy opinion, explaining why they opposed the antibody tests. That same day, Oxford University scientists declared the Wondfo tests unreliable, leading the United Kingdom to seek reimbursement for its purchase of millions of the tests from the Chinese company.

Legere said recently, in written responses to questions, that his company eventually discontinued the use of these particular tests “when we internally tested other tests that we found performed better.”

Becerra would push again for the companies’ testing services the next week, on April 14, when he invited company representatives into commissioners court to make a final pitch.

By this time, relations between Hayungs and his associates had begun to deteriorate, a state of affairs Hayungs blames on Smith, who he claims cost him a $1 million deal between MRG Medical and MD Box by raising questions.

At an April 14 commissioners court meeting, the CEO from AnyPlace MD, Shane Stevens, said multiple times that he was not involved with MRG. Legere, the founder of MD Box, would later say in an interview with ProPublica and the Tribune that Hayungs wanted a job with his company and wanted it to purchase MRG.

Hayungs “was moving very fast,” Legere said. “I don’t do business that way.”

At the same meeting, Becerra conceded that the MD Box and MRG Medical marketing efforts were “overreaching” and “ambitious.” Despite that, he told AnyPlace MD and Reliant Immune Diagnostics representatives: “I think it’s wholesome, and I think it’s wonderful.”

Commissioners took no action on the companies’ pitch. In an April 18 email to fellow Commissioner Debbie Gonzales Ingalsbe, Becerra said he believed the opposition to the antibody testing was “politically motivated.”

“I truly expected the commissioners to help arm me with the tools needed to keep our community safe, I never expected them to be complicit deniers,” he wrote.

By the end of April, any potential testing deal with the companies that Becerra had pushed for was dead.

Aftermath

In the aftermath of Becerra’s failed efforts, Hays County would eventually partner with the Texas Division of Emergency Management to set up mobile testing sites throughout the county. AnyPlace MD — without MRG’s involvement — would secure a contract with the city of Austin to run one of its testing locations. COVID-19 infections would surge across the state, including in Hays County. The months dragged on.

Then, in the summer, Hayungs popped up again. His company, MRG Medical, landed on the Aug. 11 commissioners court agenda for the county’s annual budget workshop, typically an opportunity for department heads to make their cases for funding. Private companies were an unusual addition, but Hayungs got a spot to again try to sell his virtual health care platform to Hays County more than a year after he’d originally pitched it.

Before the meeting, Hayungs told a ProPublica/Tribune reporter he was thinking about filing a lawsuit against Smith for ruining his chance to sell his company to MD Box. Maybe he’d sue the rest of the commissioners court, too, he said.

Hayungs created his own meeting agenda and emailed it to all the commissioners. The items listed included discussing “BAD PRESS” and “Takeaways and NEXT steps to move FORWARD to do what’s RIGHT for HAYS County and its Citizens, NOT for other interests or agendas.”

He came with a similar pitch as the one he’d made the previous year, but instead of launching into his presentation, Hayungs tried to turn the meeting into a prosecution of Smith.

Smith was ready, too. He’d gathered every important email and document he’d collected over the previous months.

What unfolded was the culmination of more than a year of frustration, suspicion and recrimination.

Hayungs played videos of his company’s COVID-19 test kit press conference, showing Becerra extolling the virtues of the tests. He played a heavily edited video of the April 14 commissioners court meeting, trying to show Smith undermining the testing efforts.

“Mr. Smith,” said Hayungs, as the video played, “you might want to pay attention over here.”

Smith countered by producing his own video, as well as emails and documents that highlighted the many questionable claims Hayungs and his associates had made over the previous months.

The back-and-forth grilling took up most of Hayungs’ presentation time.

Finally, Becerra stepped in, urging Hayungs to get on with his presentation, but never acknowledging all he’d done to help the businessman.

Hayungs again expressed frustration that the county had yet to jump at his offer.

“I was trying to put Hays County on the map a year ago,” he declared, echoing the same words he’d said to commissioners the previous summer.

Even after the explosive exchange, Becerra remained ready to help Hayungs advance his goals. He suggested a meeting between his Health Department director and Hayungs.

“Maybe you could schedule a time to meet or meet now?” Becerra said. “Whatever works. … You seem to be offering something that’s highly wonderful. Let’s see if we can make it a fit.”