Health officials in Hays County and at Texas State are reflecting on the lessons learned and challenges faced after the university’s first full semester operating under COVID-19 protocols.

Student Health Center Director Emilio Carranco believes Texas State’s COVID-19 response, although planned with many uncertainties surrounding infection rates, treatments and vaccines, was effective in limiting community spread.

“I have to say that I’m very pleased,” Carranco says. “We weren’t quite sure how effective the prevention measures would be. We thought they would be, but until we actually implemented them and tested them, we couldn’t be absolutely sure.”

Hays County Judge Ruben Becerra praises the university’s response to the virus and believes it has played an instrumental role in preventing the spread of COVID-19 throughout the county.

“I have no problem speaking truth to power, and I’m going to tell you that I’m really impressed with the university’s effort on [COVID-19] response,” Becerra says. “The overall response of Texas State’s leadership [and] students [has] been good. You can find anywhere examples where that’s not the case, but I will call those exceptions, not the rule.”

Carranco says the data provided by the university’s tracing and testing practices indicated its preventative measures were working and that some cases of “spread” within departments were coincidences.

“As we gathered all of that information during the course of the fall semester, what we discovered is that our prevention measures really were effective,” Carranco says. “We didn’t have any transmission in classrooms, in department or in the residence hall. In the residence halls, I think the biggest challenge was just roommate-to-roommate spread. We did see some of that in the residence halls, but we never saw evidence that infection was spreading across a residence hall.”

Carranco says cases would appear on the same floor, but the university’s investigations revealed cases could be attributed to social activity outside the residence halls, not within them.

Haley Sutton, who graduated from Texas State in December 2020, served as a resident assistant at San Gabriel since August 2018. She says the university’s health and safety protocols were thorough in theory but not in practice.

Sutton says not all residence halls were enforcing the safety measures as thoroughly as hers, causing friction between the residential assistant staff and residents. She says many residents argued that the barring of guests in some dorms was incongruous with residents eating maskless in dining halls or leaving the halls to party.

“[I] believe President Trauth [said] that they noticed that everyone was on campus following guidelines and that everything was going well on campus in terms of transmission,” Sutton says. “And that’s probably true for the most part, although I can say I saw a lot of people not following guidelines all the time, so they must have just not been around often. I’m satisfied with what they said was going to happen, but it was inconsistently applied and then there was nothing for us to do when we found out that it wasn’t really working for the students or the [resident assistants].”

The increased access to testing on campus assisted in the success of reduced infection rates, Carranco says. When Curative Inc. set up its testing station in collaboration with the Texas Department of Emergency Management on Sept. 28, the testing significantly increased from what the Student Health Center alone could provide, which was 200 to 300 tests per week.

“On average [after Curative’s arrival], we were probably testing about 1,200 people a week,” Carranco says. “Toward the end of the semester, we were starting to test about 1,500 people a week. [That] was really powerful data. We could look at the data and make good decisions about what we needed to do on our campus, given the prevalence of the infection in our community.”

The Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) test administered by Curative was the subject of a Jan. 4 warning by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) stating a risk of “false results, particularly false-negative results.” Carranco believes the nature of the PCR test, as a method, is solid. He recognizes it as the “gold standard” of testing and says all PCR tests look for viral ribonucleic acid (RNA), meaning one could “assume” that the Curative tests perform as well as other PCR tests.

Carranco says the FDA is looking for Curative’s data on asymptomatic cases. According to the aforementioned FDA statement, the use of the test is “limited to individuals who have shown symptoms of COVID-19 within 14 days of onset of the symptoms.”

The university is prepared and approved to roll out any variant of the vaccine, according to Carranco, although it would prefer to avoid “two or three different vaccines” in the rollout to steer clear of potential logistical problems. However, all that is missing are the vaccines themselves. The university submitted a request for the vaccine, which was not allowed until the week of Jan. 18, Carranco says.

When vaccinations are ready to be administered, they will take place in the ballrooms of the LBJ Student Center on multiple dates due to the likely piecemeal nature of the vaccine distribution, as well as to reduce the possibility of overcrowding.

One of the changes to COVID-19 efforts Carranco says he would have implemented earlier was the creation of the Texas State COVID-19 Dashboard, which was driven by a desire for more information by the university community early in the fall semester. He says the university could have anticipated the need for more details and transparency. He also wishes the university could have better conveyed its adaptability and willingness to make changes.

Carranco says he understands the desire for information about positive cases in classes. He says providing details over positive cases is a legally and morally gray area for Texas State.

“Ultimately, the only reason to share information was if it was important to do so and if there was something that you needed to do in response to that information,” Carranco says. “If positive cases thought that their privacy wasn’t going to be protected, that their information was going to be shared broadly, then the risk was that they would not report. And then we wouldn’t know at all.”

Carranco believes the rural setting of San Marcos helped limit transmission of COVID-19, as neighboring communities like San Antonio and Austin have naturally higher infection rates because of their density.

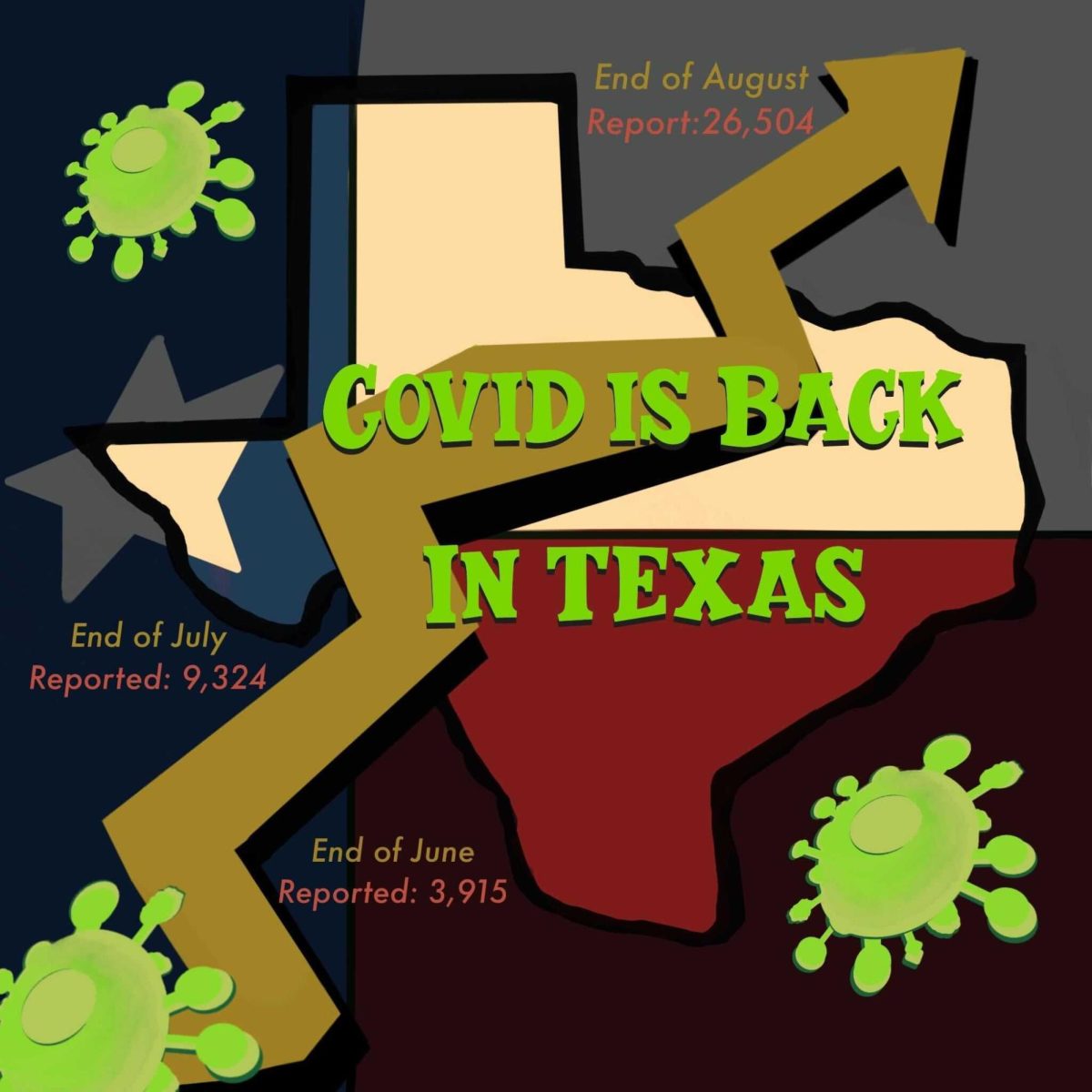

Though, when calculating infection rates by using confirmed cases as of Jan. 25 via the Texas Department of State Health Services, as a percentage of total county population estimates in 2019 by the U.S. Census Bureau, Hays County is in the middle of its two largest neighbors, Travis and Bexar County.

Hays County registers a 6.04% infection rate, while Travis and Bexar register at 5.10% and 6.67%, respectively. Students living off campus and who do not report positive COVID-19 tests outside the university’s parameters are not factored into the count, which could create a margin of error.

Carranco is uncertain whether the university helped lower conditions. However, he says he does not believe gatherings in San Marcos and around the Texas State community were the fault of the university.

“[Coming] to class, living on our campus, working on our campus doesn’t increase your risk of getting COVID-19,” Carranco says. “What I’m challenging is this idea that just because we bring students together here [is somehow] leading to a much higher level of transmission than if those very same students were back home in Houston, or Dallas, or the Valley or wherever they live.”

Sutton thinks while on-campus activities may not have increased COVID-19 rates directly, having students on campus and attending classes was not a smart move.

“I think, well, you brought the kids back to school and campus life might have not spread it as much on campus; it was probably not helpful at all,” Sutton says.

Becerra agrees with the sentiment that Texas State was not largely responsible for the actions of students off-campus but did admit to a degree of nervousness whenever students arrived at the beginning of semesters or breaks. He adds he was aware of the difficulties students faced while being socially restricted.

“Every time we have the influx of Bobcats coming back we were always like, ‘Gasp, what’s gonna happen?’,” Becerra says. “As a father of two 25-year-old [former Bobcats], I’m very cognizant of the difficulties [of] what it’s like to shut down youth for a year and say, ‘You can’t. You can’t. No, you can’t do that either. Nope, not that either.’”

When looking back on the lessons learned, Carranco expresses gratitude for the cooperation of students in adapting to what the university asked of them and for university leadership being flexible enough to implement changes.

He says spreading knowledge over the effectiveness and safety of vaccines is key to a return to normality, citing other medical experts who state a vaccination rate of at least 70% would be necessary to develop herd immunity.

“We’re assessing the situation every week,” Carranco says. “There’s so much going on right now; I think the vaccination effort is so key to our recovery that a lot of it depends on how well the state and the country does and getting people vaccinated.”

Categories:

Community reflects on first full semester during COVID-19

Ricardo Delgado, News Reporter

February 10, 2021

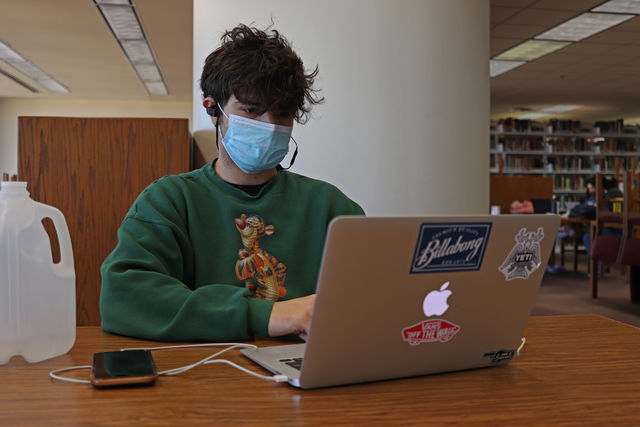

Students practice social distancing while they work and study, Sunday, Feb. 7, 2021, at Alkek Library.

0

Donate to The University Star

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover