Editor’s Note: For the remainder of the school year, The University Star will take on “The 11% Project”, an examination of Black students at Texas State through History, Election, Hometowns, Activism, Creatives and 10 years from now.

It took Tafari Robertson two years post-graduation to process the trauma he endured as a student at Texas State.

“In the year [following] everything that happened on campus…I had graduated, but I was still in San Marcos,” Robertson says. “That was just, like, a really rough year for me because it was leaving the activist space. You know, it’s hard to look back on and feel like you really did everything you could have.”

Black students, like Robertson, have sometimes had to take on the job of the institution. Efforts to push for the university to denounce white supremacy, establish an African American Studies minor and hire and retain more Black faculty members came at the cost of their own well-being.

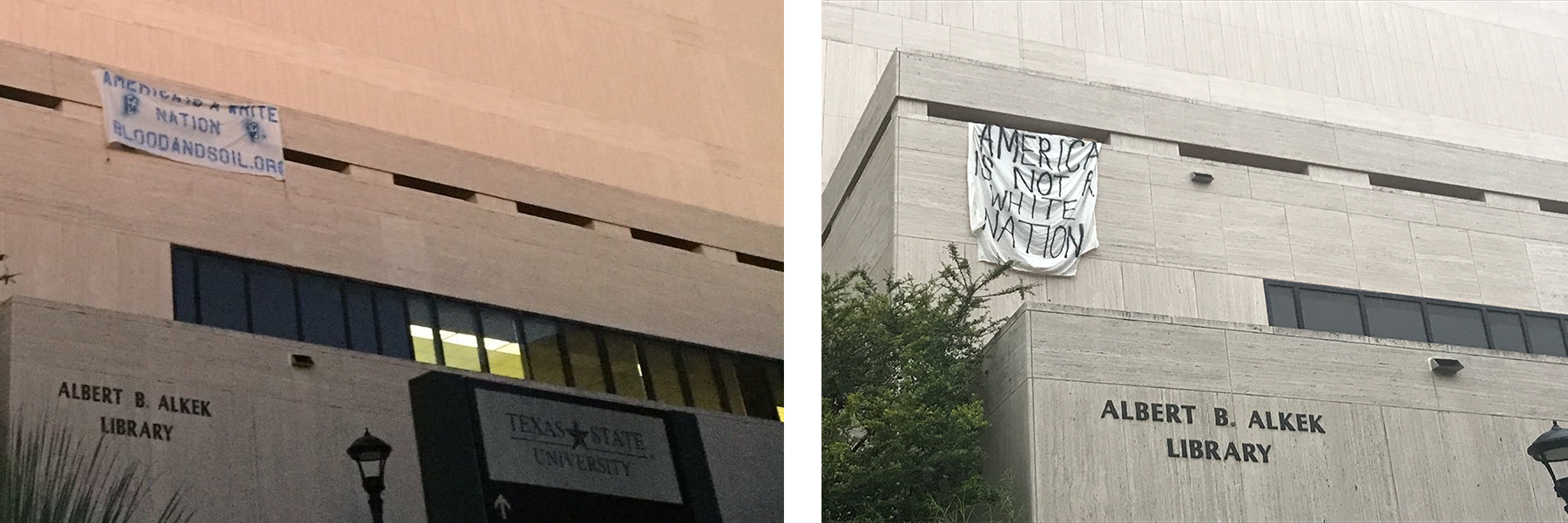

Black students’ years on campus have included meetings with university officials in the aftermath of events that made them question why they enrolled. Racist flyers. A white supremacist banner hanging from the university library. Failed attempts to get elected student representatives to attend the impeachment trial of a student body president who posted racist and sexist material to social media.

In this installment of The 11% Project, The University Star, along with the student activists who were involved, take a step back in time to revisit major protests that occurred on Texas State’s campus in recent years and examine how they have impacted the students and university since.

The March on Clegg

Over 300 students marched to the LBJ Teaching Theater on the cold, overcast winter afternoon of Feb. 5, 2018, calling for the impeachment of then-Student Body President Connor Clegg.

The event, formally known as the March to Demand Action to Racism at TXST, followed the resurgence of racist and sexist posts from Clegg’s personal Instagram account just four days prior. The account revealed photos of Clegg with people appearing of Asian descent featuring racist and sexist hashtags.

The university administration took no action against Clegg other than the release of a statement from University President Denise Trauth calling racism, in any manifestation, “abhorrent” and stating Clegg had apologized — a response viewed by some in the Texas State community as lackluster.

Students and members of the Pan African Action Committee (PAAC) gathered on the Quad by the Stallions statue at 4:40 p.m. to call for the impeachment of Clegg and voice their concerns with the university — an institution they believed had a history of unsatisfactory responses toward racism.

Najha Marshall, a Texas State alumna and former president of PAAC, was a freshman at the time and helped organize the march as a member of PAAC. Marshall says while she felt empowered by the march, she felt angry the protest needed to occur in the first place.

“As a freshman, one of the things that got me to come to Texas State, as well as many other students of color, is like the picture of diversity [Texas State] sells,” Marshall says. “Seeing, like, that we’re sitting here having to do all of this just to get someone who is racist out of office is just not right. And so, it makes you feel angry, not because like as a Black person in America, but as a student who’s paying to have an education at the school.”

Shortly after Trauth’s statement was released, flyers and graffiti were found on campus calling Clegg racist and Trauth an enabler. Some graffiti stated Trauth supported racism and called for her to step down.

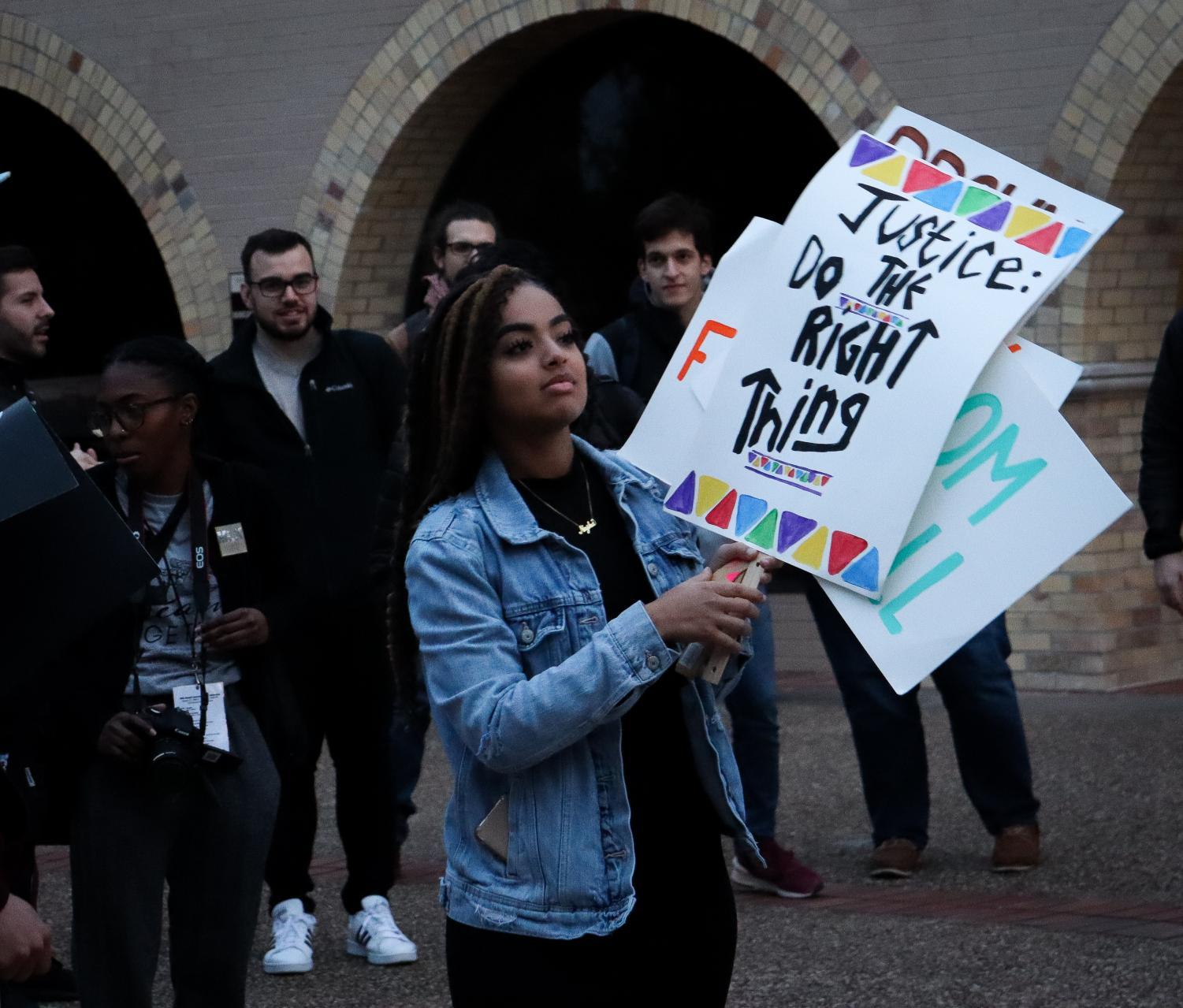

Mena Yasmine, a freshman at the time who had just joined PAAC and Black Women United, saw the flyer about the march circulating on social media. She says despite not knowing many people within her organizations, she felt compelled to attend and was one of the first people to appear at the Stallions.

“I just felt like it was something I had to show up and voice my opinion on,” Yasmine says. “I specifically remember buying these poster boards and, you know, trying to figure out what I was gonna say…I think my sign said, ‘when will this institution serve me too?’”

Nahara Franklin, a member of PAAC and Black Women United at the time, says she recalls exactly how the crowd looked.

“I remember seeing a majority of the crowd be like students of color, which was really endearing, but also kind of sad,” Franklin says. “I also remember seeing mostly women, which was also kind of sad, mostly Black women.”

Months prior to the march, in November 2017, following the publishing of the column “Your DNA is an Abomination” in The Star, Clegg released a statement via Texas State Student Government’s official Twitter account calling for either the resignation of The Star’s editorial board or the defunding of the news organization in its entirety.

PAAC quickly released a statement demanding the immediate resignation of Clegg for his “record of disregard for Texas State’s Black and Latinx populations,” adding that it stood in solidarity with The Star.

“As an organization that concerns itself with concepts of race on campus and the pervasive institutional racism that our community faces, we find Connor Clegg unfit to serve as student body president of such a diverse student population and ask for his immediate resignation,” PAAC says in the statement.

PAAC cited Clegg’s silence in addressing Nazi-tied fliers and banners posted around campus in 2017, his prevention in passing legislation to allow for an immigration attorney on campus and his utilization of a veto following the senate’s approval to sign on to an amicus curiae brief filed by the Mexican American Legal Defence and Educational Fund against Senate Bill 4, known as the “show me your papers” law.

Emmy Orioha, who was a political science junior and the president of PAAC at the time, says the organization’s central goal was only highlighted by the news of Clegg’s actions.

“Our goal was always, how do we institutionally change Texas State so that 20, 30 years from now Texas State is a radically different organization that meets the needs and [is] able to be home for a diverse group of students,” Orioha says. “And when the things happened with Connor Clegg, it just felt like the antithesis of what we wanted for our school, and that’s really why we stepped up in that time because there had to be, to us, a real declaration.”

Orioha, who was repelled by Clegg’s attempt to label his past remarks as “locker room talk”, says he had several one-on-one discussions with Clegg to mediate the situation to no avail.

“I actually began talking to Connor as early as December (2017) about all of this. I went to his office, I called him, I texted him, had conversations with him, but he just didn’t back down,” Orioha says. “And so I told him, and I think we’ve kind of made it clear, that if you weren’t willing to really recuse everything that you’re doing, then steps had to be taken to remove him.”

While chanting “hey, hey, ho, ho, Connor Clegg has got to go”, the group marched through Alkek Library to the LBJ Teaching Theater at 6 p.m. where Student Government hosted an open forum.

The group then delivered a petition with more than 1,900 signatures calling for Clegg’s removal. Despite hearing word of a large “silent majority” in support of Clegg, Orioha says he was happy to see the majority of those present were there to protest for Clegg’s removal.

“The entire place was completely full. People were standing all around. [There] was probably like just hundreds of students that day,” Orioha says.

While Marshall says the march was effective in showing the Student Government and university administration that they built a united front, she believes it was more symbolic than consequential.

“I don’t really think much happened after the march. I feel like the march and the protests, like, they were more symbolic just to show like, this is something students care about and we are going to join together to get it done,” Marshall says.

After the march, Alissa Guerrero, an international relations senior, and then-Student Government Sen. Claudia Gasponi drafted articles of impeachment against Clegg and submitted them on Feb. 16, 2018, stating he had violated six articles within the Texas State University Constitution.

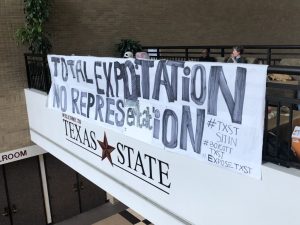

Student protesters attended Clegg’s impeachment hearing on Feb. 27, 2018, in the LBJ Teaching Theater, some with duct tape over their mouths to represent their platform, “silence but not silenced”. However, to the protestors’ dismay, the Student Government Supreme Court unanimously found Clegg not guilty of any violations. The move sparked outrage among students and led to the #BoycottTXST movement.

Gasponi later filed an appeal against the Supreme Court’s decision on March 19, 2018, to then-Dean of Students Margarita Arellano, which was approved on March 28, 2018, placing Clegg’s removal back on the table. The appeal allowed Student Government 10 business days to call a vote.

On April 11, 2018, the day of Clegg’s second impeachment trial and a joint session with Student Government and the Graduate House of Representatives, protesters in attendance pointed out a noticeably absent theater.

“As they started calling roll, you know, people are starting to get angrier and angrier because we’re realizing they’re not there, what is going on? Like I can’t believe they’re doing this. And then Clegg is sitting there in the front row looking smug as hell, like smug as hell,” Yasmine says.

The Student Government failed to meet quorum that day with only 19 of its total 40 members absent, effectively ending the session.

“That is when all hell broke loose, and we were kind of just forced to do what we needed to do to fight back, so we were all devastated,” Franklin says.

“And then that’s when I jokingly said, I don’t remember who was around me, but maybe we should just stay and not leave, and then someone’s like, ‘Yeah let’s have a sit-in’. Then the word got out and then we all just moved.”

Student sit-in

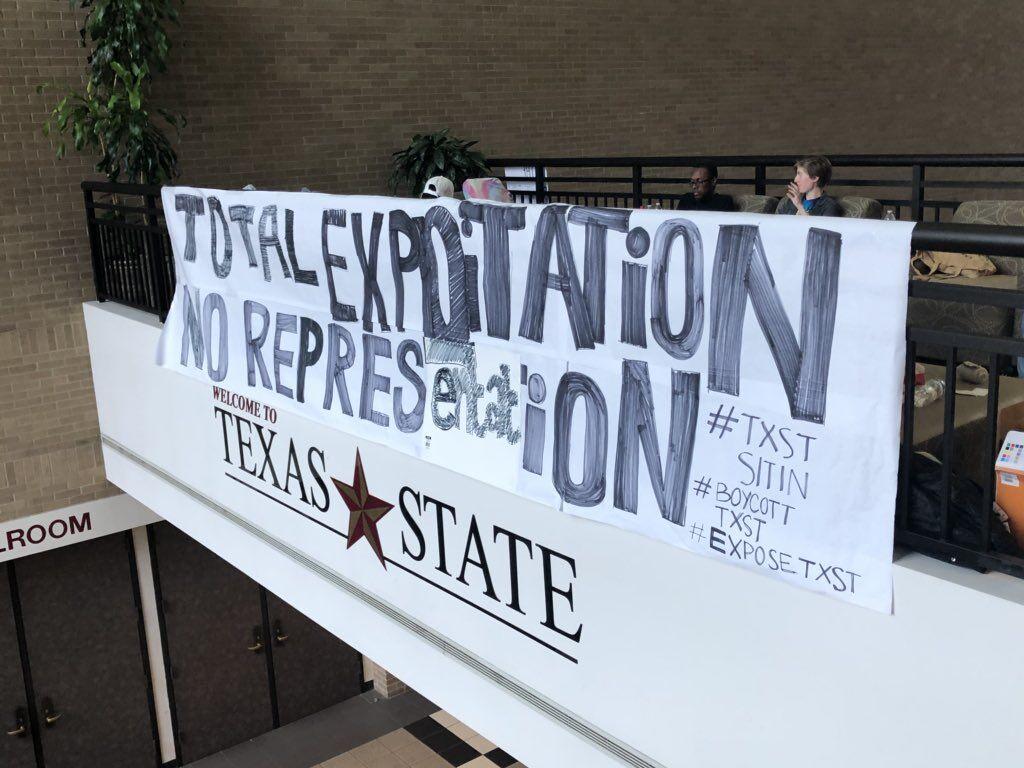

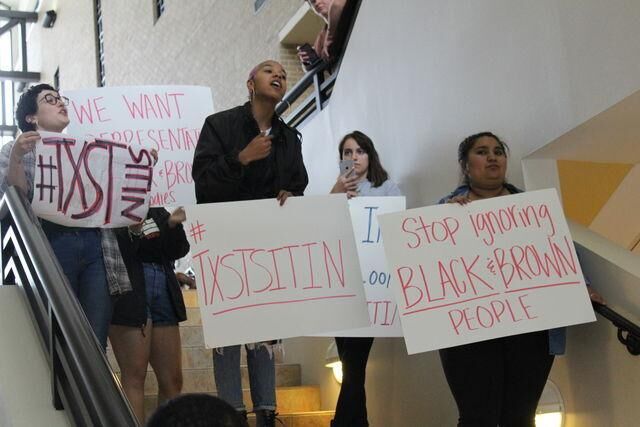

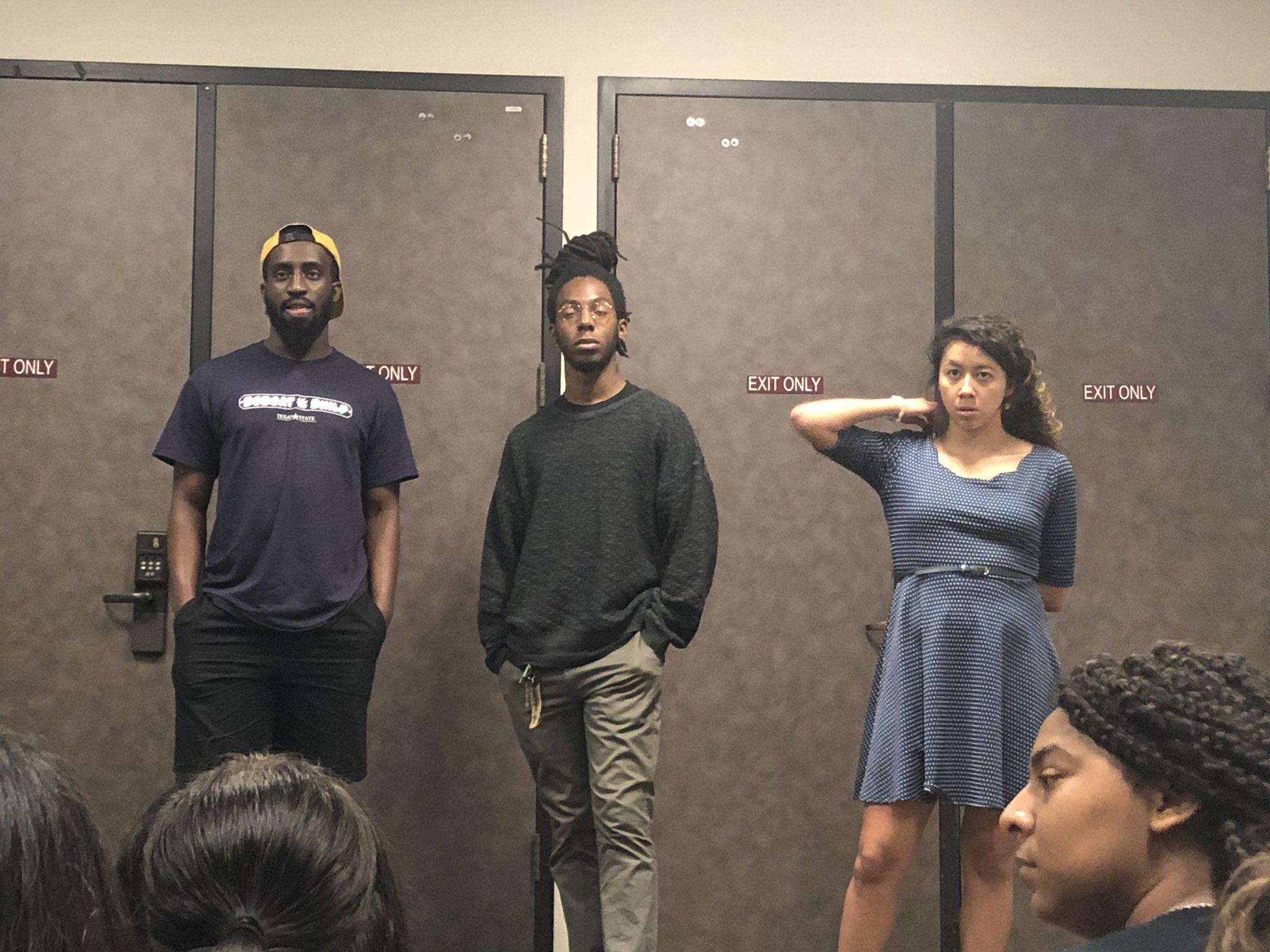

After feeling unheard and disrespected, students attending the April 11 Connor Clegg impeachment trial rallied together on the fourth floor of LBJ Student Center and conducted a sit-in.

The decision to have the sit-in was a quick team effort among the protesters, led by Robertson, former president of PAAC and University Star columnist.

“I remember walking into the auditorium; I grabbed the mic and I said, you know, there was a lot of students who were there specifically for this moment because it’s what we had been building towards, and I remember grabbing the mic and saying we wouldn’t leave the auditorium until Connor Clegg came back,” Robertson says.

Robertson felt personally responsible for everyone attending the sit-in as he was the one to start it. He says he felt a lot of pressure in reassuring that nothing escalated to an uncontrollable point.

“I think it was, you know, for some, it was like a moment where it’s, like, a lot of good friends and support systems came together but, for others, it was just like being pushed to the edge by the incompetence of our school, you know, like, students shouldn’t have to spend the night on like, a hard, cold floor, just to get like, the very basics of [their] education,” Robertson says.

On the second day of the sit-in, Yasmine says the group decided to make and give out pamphlets explaining the recent events and why students were occupying LBJ.

After conducting meetings and talking among one another, the protesters came to an agreement that they were not only upset because of Clegg’s failed impeachment but also the overall infrastructure of Texas State. The sit-in goers took advantage of their situation by establishing a list of demands for the university to act upon.

The students asked Arellano and Trauth to remove Clegg from office, to denounce the Student Government for its inability to represent constituents and for Texas State to adhere to the needs of its students of color. The students said they would not leave the student center until their demands were met.

Yasmine says, at first, the university ignored their demands, which discouraged the students.

As the sit-in continued, Yasmine says they were treated with more respect by the administration, but only their demands of a timeline were considered. A meeting was arranged with Robertson to discuss what the university could do.

“All the people who have, like, control over different aspects of how Texas State runs were there to kind of like, answer questions, but really to just like, show [a] face, you know, at that moment, which was ultimately a waste of time,” Robertson says.

After the meeting ended, the students felt defeated. Yasmine says anger finally resonated as Jackie Merritt, Clegg’s vice president, left the building with a police escort, which was presumed to be for her safety when everything got out of hand.

“It’s even crazy to think how we ended up in that situation but like we were mad that they were basically getting a police escort off school,” Yasmine says. “They were getting a police escort off campus because of a mess or because people were angry because of the mess that their office basically created, and obviously we don’t [expletive] with cops. Everything from that point on just escalated.”

The group, the police and the vice president entered a parking garage. Yasmine says the reason for them following Merritt was due to the desperation and need for answers.

“We’re like, we just want them to answer questions,” Yasmine says. “We want them to take responsibility, be held accountable for these things and denounce something, like keep in mind that throughout this process, Denise Trauth never, like, publicly denounced, you know, Clegg’s actions or racism, but she had the audacity to call [the ‘Your DNA is an Abomination’] column abhorrent and racist.”

Yasmine says the amount of disappointment, unanswered questions and the university’s incapability to denounce racism was fuel to the fire.

“We all form like this chain blocking, like, the cruiser that was escorting them and one of our friends, he graduated that year, Russell, you could just see, I think there’s like a photo album of this whole situation somewhere in the Texas Tribune, somewhere, where you can see like, the emotion like bubbled up inside of him,” Yasmine says.

“This emotion was like bubbling up inside him and he’s just like, bloody murder screaming like, ‘I’m tired of this, I’m tired of this,’ basically just screaming like into the void like he was just tired of it, and I can understand. So, we’re all crying and we’re all blubbering messes just here, just on this chain-link like, ‘no like where are y’all going,’ like we need something, like give us anything, crumbs, like all we’re asking for is the bare minimum,” Yasmine says.

As they blocked the vice president from leaving, more police arrived and were able to calm the students down and persuade them to leave. Yasmine explains, however, that this led to a bigger situation.

“I think after that, one of the cops tries to grab Russell even though we’re moving like, you know, the situation has de-escalated and everybody’s like leaving, and doing whatever they have to do and then [someone] got grabbed by the officer and started to have a panic attack and it was just a mess,” Yasmine says.

Afterward, the sit-in continued. Yasmine says with more donations and resources the sit-in became easier to manage, but the students needed to make a decision on whether to continue.

“We started brainstorming on like, you know, what to do now, because it’s clear that the administration isn’t hearing us, they aren’t listening to us, they’re just kind of like, ‘okay, they’re going to get tired or whatever,’” Yasmine says. “I think a few months before Howard [University], had just had their sit-in, so we spoke on a call with those student leaders and kind of, you know, wanted to know what they did, because it was so successful for them and we started like, organizing events and things, you know, to make it less stressful.”

On the last day of the protest, students held poetry slams and allowed one another to take breaks. That same day, a timeline was released from the administration laying out the demands they would attempt to meet which, to Robertson, was a success.

“All of our demands from the sit-in [were met] and that’s something that I have to remind myself is that that was the only sit-in in Texas State history that was successful,” Robertson says. “I think maybe one of the only successful student protests in history, the last time they did a sit-in at Texas State, all of the students got expelled. So, it was a big deal that we basically did have them kind of on the ropes in the sense of like, basically, within the first two days of our sit-in, all of our demands were met.”

After the timeline was released, the students decided to end the sit-in by a majority vote on April 13.

“I think because mostly everyone was tired, it was finals, getting [close] to finals times, it was the end of the year…So, we took a vote and in the end, we voted to leave,” Yasmine says.

While the university met the group’s demands, Robertson says feelings of frustration toward Student Government and the university administration still lingered.

“It was raining that night, which, you know, only put salt in the wound,” Robertson says. “Not only are a lot of students frustrated, at this point, nobody actually feels good…in a way we kinda won but this moment was like very, very bittersweet, much more bitter than sweet.”

Just three days after the end of the protest, Clegg was impeached and removed from office during a joint session between the Student Government Senate and the Graduate House of Representatives.

“I think the [impeachment] rejuvenated, you know, a lot of the students who were worried that they had, you know, come to show support in the sit-in [for] ultimately nothing…Connor Clegg was a big rallying point that students could make a symbol [to represent the feelings toward racism at Texas State],” Robertson says. “When he was impeached, even though the [Student Government] manipulated it in a very political way, a lot of people were able to sort of feel good about that moment…a lot of just like students of color, Black and brown students, were all very happy about that moment.”

However, a month later in May 2018, right before semester finals, four protestors who had altercations with UPD while in the parking garage on April 12 were arrested and charged with Class B Misdemeanors of Obstruction of Highway and Interference with Public Duties.

“Basically, I’m wondering, are they coming for me next? [One of the students was] my best friend at the time. I’m like, ‘Oh [expletive] gotta go get [them] out of jail.’ So, we look up their charges when they’re booked and you know, and inside the jail and it’s for obstructing a highway…turns out that what happened in the parking garage was grounds enough for arrest and they decided to wait so as not to get everybody riled up again. Instead of doing it that day in the parking garage, they wanted to wait until literally like a couple of days before finals,” Yasmine says.

The money from the sit-in’s GoFundMe was enough to cover each person’s bail, but Yasmine says the arrests coming weeks after the incident angered her.

“We went on to the end of the school year, I moved out of my dorm,” Yasmine says. “A bunch of people still were uncomfortable on campus because of what happened with the arrest and we went into the summer into a haze, like in a haze, basically.”

Robertson says the battles student activists have to fight on campus take away from the personal good they could be doing for students.

“The Connor Clegg [situation] really drew us into like a combat, like into a more combative mode, that I think ultimately took away a lot of the energy that we might have been able to spend directly helping students of color,” Robertson says. “It was a good moment for people to see but, I don’t know, I think we had done so much leading up to that. It is a little bit disappointing that it’s like, that is the big event that we left with, you know, when there were so many positive things that had happened.”

Robertson says students have more power than they are aware of and can use it to make important changes.

“I want students to see the things that we accomplished and understand that it was the students who did that. It was first-generation students, it was bilingual students, it was immigrant students, it was undocumented students, it was trans students, it was, you know, at large, it was Black women who really were a part of these movements, at least consistently,” Robertson says. “So, it was all the people who are, you know, taking on some of the full force of that oppressive system but we, you know, pushed and were able to make a difference and force them to, because in the same way, they rely on us, you know, for our money, and for a lot of things.”

May 1

During the 2019 spring semester, the Texas Nomads SAR, an outside political organization that students associated with white supremacy, announced it was planning to visit Texas State’s campus.

The decision to visit Texas State, the group says, was in defense of Texas State’s conservative student group, Turning Point USA (TPUSA), after the Student Government proposed and passed a resolution to ban TPUSA from campus.

As rumors erupted, students planned to protest the group’s arrival. After hearing about the student protest, the Texas Nomads decided to call off its planned visit to avoid possible conflicts. Despite the group never arriving on campus, students from different sides of the political spectrum got into a dispute. Four students of color were arrested — one of whom was previously arrested the year before.

Camara Burleson, now a psychology senior, was unaware of the situation as she was leaving her class and just saw the Quad filled with students.

“When I came out of class, I just remember everyone being around the police station standing around and [everyone] was yelling and stuff; the news was there I think. It was just like, ‘What’s going on, what’s happening,’ then you find out one of your friends got arrested,” Burleson says.

Destiny Whitaker, a Texas State alumna, recalls many people talking about the protest days before it happened and that people had skipped class to attend it. She waited until her classes ended to go to the protest and, by the time she arrived, the Quad was flooded with people.

“I went to class and then I came out, and I tried to meet my friends by the police department because that’s where everything was happening, and it was literally like that meme where the guy goes out and, like, he can’t find anybody, because that’s what it was. The whole place was so crowded and they were like, ‘So and so went to jail,’ ‘This person punched this person,’ it was literally crazy,” Whitaker says.

Corey Benbow, former Student Government president who was sworn in just weeks prior, heard about the protest and knew beforehand that students planned to protest against the Texas Nomads. But he did not expect what would happen that day.

“When we get down there, the scene for me is very chaotic because there’s a large crowd of students, everybody is saying a lot of different things, everybody’s having encounters with the police. Of course, at this point, you see all these administrators down there…it was just kind of this mix of all kinds of things that were going on. So, the [police] chief wasn’t there yet and then I saw, you know, all these state troopers and all these police officers and my mindset at that point is that I’m just kind of an observer. But, as the situation got more intense, and people started, you know, kind of really getting riled up, I thought to myself, ‘nothing good can come from this situation,’” Benbow says.

Benbow attempted to calm the crowd out of fear the situation would escalate and result in more student arrests.

“That day…I was in a very vulnerable spot, and I took a calculated risk of asking the crowd to calm down, disperse, and to say that nothing good can come from this because I feared that they were going to send more police as the crowd continued to increase and I thought, you know, this just wasn’t going to be a good thing,” Benbow says.

Burleson says the arrests confused her, considering the Texas Nomads never came to campus.

“It was just like a lot of misinformation going around and for them to not even be there I was trying to figure out, like, ‘why did an altercation break out with the police against the students?'” Burleson says. “The little jail on campus, that’s where they were holding them, and we were basically, like, getting news from people inside. It was like, ‘They’re waiting to process them’ and, ‘They might get a charge, they might not,’ ‘We don’t know how long they’re staying,’…it was just a bunch of miscommunication and misinformation going on and around that whole day.”

Turning to social media as an outlet, students kept one another updated on the situation, but Whitaker says not hearing from UPD bothered her.

“There was a whole bunch of misinformation then the buzz started with the students and then it moved to Twitter and people are talking about it and it’s just like everywhere,” Whitaker says. “That day it was just like a whole bunch of people talking; no one really knows the truth and the police have a platform to let people know what’s going on. UPD is on Twitter, they send out alerts and they weren’t even making an effort to make things clear either, it was just really shady, the whole situation was just really shady.”

Whitaker believes UPD used the situation as an opportunity to attack outspoken student activists.

Police Chief Laurie Clouse, however, would later put out a statement that says “the incident that led to the arrests began when one student took a hat off another student’s head and fled.”

“Police officers quickly interceded and directed the student to drop the stolen property. The student refused multiple directives and was then detained with the intention of being given a ticket for theft. The student was later arrested after providing a false identity to the police,” Clouse says in the statement.

Clouse says a student ran to the officers during the situation and “began to interfere.”

“After refusing to comply with the officers’ directions, this student was arrested for interference with public duties,” Clouse says in the statement. “When the students were escorted into the police department, other students followed and one additional student was arrested in the police department lobby for interference. A fourth student was arrested and charged with disorderly conduct outside the police department.”

The four students were soon transferred to the Hays County Jail and charged. Gasponi, one of the students arrested, says they were detained because they were looking out for the others arrested. Gasponi believes the students were targeted and questions why no white students, who were also involved in the dispute, were arrested.

“I know [the other three students arrested are] really smart…And I know that they know how to interact with police officers in a way that doesn’t compromise their safety. So seeing them being arrested was really scary for me,” Gasponi says.

Gasponi says three of the students arrested were placed in the same cell and comforted one another. The three worried about the fourth student, who was placed in another cell.

“The majority of the conversations weren’t about what’s going to happen [but rather] ‘let’s enjoy.’ Let’s enjoy each other’s company. Because that’s all that we have,” Gasponi says. “We braided each other’s hair, we let each other use our body for warmth; we shared the ends of our blankets so our feet would be warm…We all knew that no matter what information we shared, talking about our charges was just too overwhelming to do so in a way that felt comfortable.”

After the events on the Quad, Benbow started to question his role as Student Government president and as a Black student.

“After that, it was really a hard time because some of them were saying this about me, ‘All skin folk ain’t kinfolk,’ and then to the point where even one of them called me a coon,” Benbow says. “So, those were kind of the experiences that I was having, but I still was steadfast in my determination to try to make something meaningful come from this. So, I took it upon myself to kind of talk to the administration about the protest that happened on May 1, about their response to the protest.”

Benbow says the actions that took place on May 1 are similar to how the university continues to mistreat its Black and brown students.

Another overnight sit-in took place on May 2, 2019, with students drafting a list of four demands: Allow the Dean of Students to handle student conduct issues rather than UPD, mandatory sensitivity training for officers, a cultural diversity requirement for the core curriculum and the creation of a campus workforce by Student Government to protect workers’ rights.

Benbow also wrote a letter to Trauth on May 6, 2019, describing his worries about Texas State’s future and the university’s response to the protest. He asked Trauth to publicly apologize “for not being proactive in addressing racial issues in our community.”

“I think that the appetite of the administration to listen to students at that point, there was none. They had already labeled Black students as troublemakers and protesters and somewhere in me, I feel like the administration feels like they gave too much from the last sit-in and they didn’t have the appetite to do it this time,” Benbow says. “I do think that even though we can’t quantitate what came out of that particular sit-in and that protest, I do think that all of this kind of noise and stuff has moved us further along than where we were two years ago. The changes are small, and so that makes them seem less significant. But I do think that the university administration is slowly but surely waking up.”

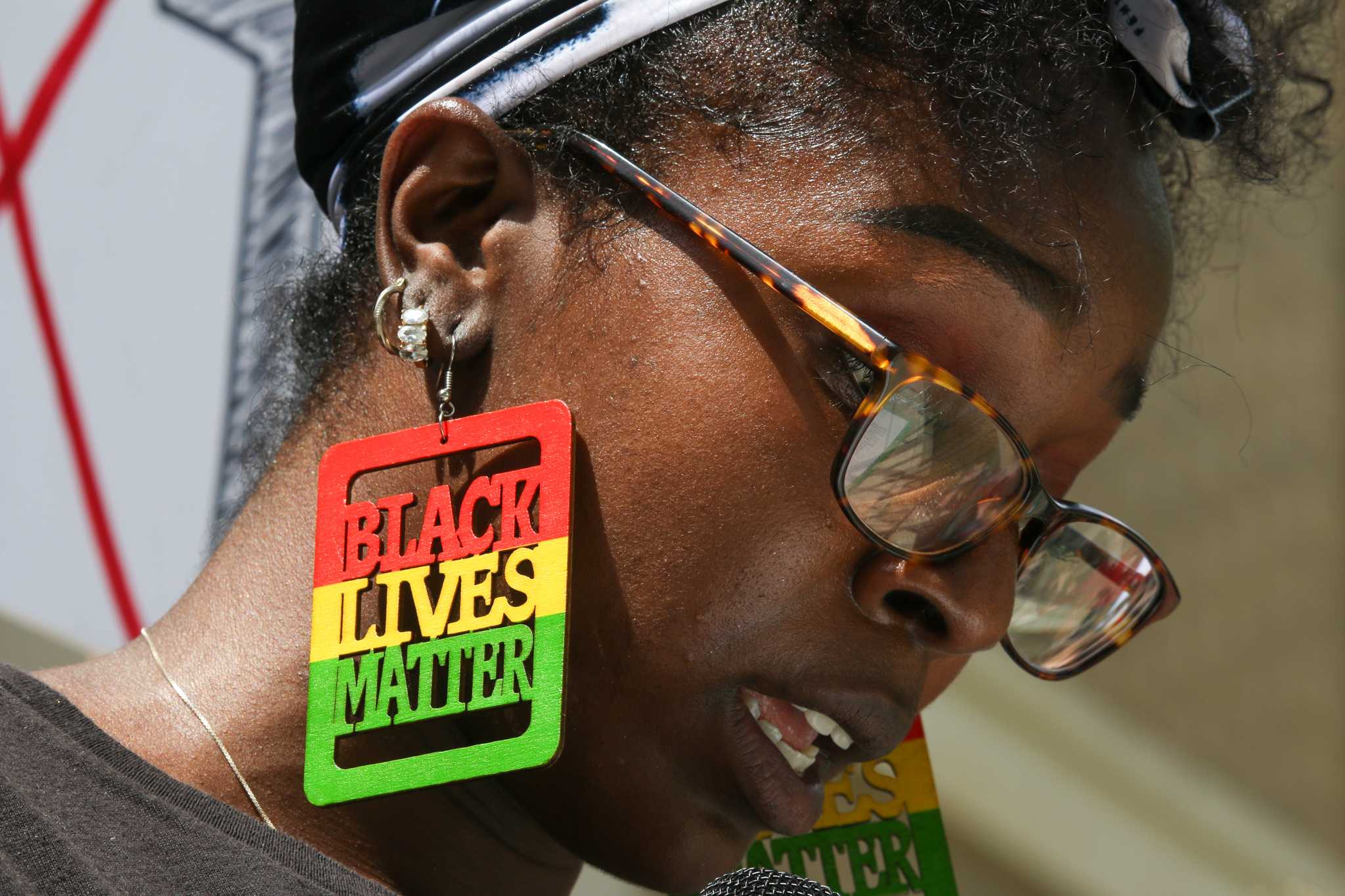

Black Lives Matter

Following the killing of George Floyd on May 25, 2020, the Texas State and San Marcos communities rallied for justice across the nation and for the university to take action to create a more inclusive environment.

On May 29, 2020, the first of several major protests took place in San Marcos. Led by Diereck Montes and Tyeronta Norman, the protest in San Marcos encapsulated the outcries against police brutality across the nation.

“Black Lives Matter has always been a thing since Trayvon Martin,” Norman says. “But, when [the murders of] George Floyd and Breonna Taylor happened, that was just too much. That was basically the straw breaking the camel’s back. I definitely saw the impact of not just protests locally and in the state of the person that died, but literally all across the nation, all across the country. It was a global impact like literally, the world stopped.”

Norman says the organization for the first protest did not take much time at all — the motivation and drive facilitated the process, and the assurance of safety propelled it forward.

“It took us maybe half a day [to organize the protest],” Norman says. “We called the public officials of San Marcos. We talked to attorneys and everything to make sure that you know, if anything happens, everybody will be safe.”

With a history of race issues on campus, the Texas State community had a moment to come together as one throughout the Black Lives Matter protests. Norman feels that the community bonded by protesting for something larger than itself and creating a space she can call home.

“I saw everybody come together, regardless of whether they were like Black, or white or Hispanic or anything. I saw people come together and literally protect each other and make each other feel like we’re a family,” Norman says. “It was just a lot of like humanitarian things that I saw throughout that day that made me feel like you know, Texas State is somewhere that I could call home, somewhere where I know there are people that actually care in my community.”

Charnae Brown, a social work senior, participated in several key protests in San Marcos, rallying at the courthouse and the San Marcos Police Department building. In total, Brown attended over 15 protests across Austin and San Marcos.

“I remember coming straight back to Texas from a vacation in Colorado with my brother, and when we came back, I went straight into protesting about two days later,” Brown says. “I began to notice that the rest of the world was sort of watching us, too. And, arguably, the rest of the world was contributing to our protesting and trying to shed light because we began to see protests erupting, not just across America, but also in different places like London.”

Brown says bringing awareness to the Black Lives Matter movement on such a hyperlocal scale made her feel the most empowered she had ever felt.

“This is during the time that [Austin Police Department] was shooting at protesters. I was in the crowd as people were being shot at, and it was terrifying, you know, but at the same time, like I said, it was very empowering because it was a moment of selflessness, where I realized I was here because this was bigger than me,” Brown says.

Statistically, Black people have a higher chance than white people of being killed at the hands of police. Protesters across the nation called for the defunding of police departments and the reallocation of those funds to other useful programs, such as education and mental health.

“UPD were going to build a whole other police station for like $3 million,” Norman says. “That’s ridiculous to me because y’all can’t even arrest students right. Why do you need $3 million for a new station when your station is right there? And when we went to go protest, they didn’t want to talk to me. They locked the doors and everything. I just think that the money that they’re using it for is not to help the greater good. It’s for personal gain for the police officers. And I don’t like that. We’re the ones technically paying for it.”

The university, however, says converting the UPD building into the Academic Testing Center and constructing a new building for UPD is included in the university’s master plan, which was approved in 2017.

“It provides the most fiscally responsible solution to better deliver student services,” says Jayme Blaschke, Texas State’s senior media relations manager.

Trauth responded to the protests across Austin and San Marcos, stating that Black lives do matter — a statement that is “not debatable at Texas State.” Trauth’s statement came after Justin Howell, a Texas State student, was shot by police at an Austin protest. For Norman, the messaging was not enough.

“[Texas State] only addressed it for real one time,” Norman says. “And it was because one of our students at our school got injured during a Black Lives Matter protest. And that was literally just the president, we didn’t really get any Black Lives Matter anything. The only time I really saw them posting something was literally organizations at our school. I haven’t gotten any VPSA emails that they send every damn day. Why is it an issue to post something about it? Why is it so hard? Why do you have to go through a protocol to post something simple as hell? But they still have time to post something for Christmas. For 9/11.”

But Norman says the impact of the protests outweighs what she feels was a lackluster university response.

“I think [the protests] will have a big impact long term. I definitely know we’re going to be in history,” Norman says.

Aftermath/Trauth response

Through a racial reckoning where institutions across the country are being held accountable for systemic issues that have disregarded the needs of Black communities, Black students at Texas State continue to advocate for lasting change across campus.

Students opened the Multicultural Lounge in 2017, a safe space for students located in the Honors College, along with the Black Student Resource Library. Texas State launched its long-awaited African American studies minor in fall 2019, a key piece to protesters’ demands in previous years.

“I never left a meeting with President Trauth or the Provost [Gene Bourgeois] feeling included. I never felt listened to, I never felt like, even at the end of the sit-in and after we left that meeting, that didn’t feel good,” Robertson says. “You could call it a successful movement or whatever; it didn’t feel good.”

Robertson says a lot of students left their activism efforts with a lot of “mental baggage” that resulted from disputes with Texas State and university police — a reality he says is a “shame.”

Following nation-wide protests against racism after the killing of Floyd, Texas State began executing a series of diversity, equity and inclusion efforts — listening sessions, the creation of task forces, planning to rename campus buildings/streets after Black and Latinx figures, a partnership with a restorative justice organization and a change in Trauth’s messaging.

“In retrospect, you know, as I look at the messages, and my messaging really started in 2016, it was probably not strong enough,” Trauth says. “If I were to do it again, if I was to go back to 2016 and write my messages, I would probably use some different language. Because what has become very clear to me is that those words, ‘we denounce white supremacy,’ those are the words that need to be said.”

Trauth says she disagrees with the sentiment that the university’s recent efforts are performative and do not address the systemic issues present at Texas State. She says the university’s changes have, culturally, made it “a better place.”

“I don’t think [our actions are] one-offs or band aids; I think that they are authentic changes,” Trauth says. “I think the reorganization that we did for our diversity, equity and inclusion staff and faculty is authentic and, it will, it is already resulting in real change, because one of the things that’s happening coming out of that, for example, is an increasing emphasis on the recruitment of underrepresented faculty, but with the real tools that our departments need to recruit more underrepresented faculty.”

There are still students and alumni dealing with the aftermath of the events that resulted in student arrests. Part of their frustration is a perceived lack of institutional support from Texas State. Others, like Robertson, feel as if students arrested in previous years were targeted by the university administration. Trauth says when a student is arrested, “that takes it out of the hands of the university.”

“If it’s inside the university, if it’s a violation of university policy, that’s different,” Trauth says. “But if a student is arrested, I have never intervened. And it’s not because I don’t care. It’s because it’s just simply not appropriate for the president of a university to intervene in an arrest.”

Student Government senators passed a resolution on Feb. 22, nearly three years later, to overturn the impeachment of Clegg. The resolution surfaced during the COVID-19 pandemic, Texas State’s ongoing diversity, equity and inclusion efforts and a record-breaking winter storm that left students without power and water.

“We are proud that after years of an illegitimate, violently achieved impeachment of the former student body president our student body has finally been heard,” College Republicans, some of whom are Student Government senators, wrote in a letter to The Star.

But Robertson says Clegg’s impeachment was only an example of what students are capable of when they unite for a bigger purpose. Not the “most important thing we accomplished.”

“Why would that even be worth pursuing at this point? But regardless, it’s like, it’s more just proof that Texas State continues to…racism continues at Texas State as an institution,” Robertson says. “Whether that flows through the [Student Government] or whether that flows through just what’s happening on campus, and how students of color are affected, in their, you know, daily lives and their educational lives. That’s something that is definitely alive.”