Editor’s Note: For the remainder of the school year, The University Star will take on “The 11% Project”, an examination of Black students at Texas State through History, Election, Hometowns, Activism, Creatives, Mentorship and 10 years from now.

Some of us didn’t even know microfilm existed until we started our timeline documenting Black history at Texas State.

It is one thing to plan and talk about The 11% Project, but the execution is daunting. Some of us trudged up the hill to the Alkek Library Archives from The Star newsroom to do our research. Others, at home, surfed the web until their laptops began to overheat.

Hidden truths and untold stories appeared before our eyes as we flipped through photographs and articles. We time traveled through decades, scouring through the Pedagog for what felt like ages and flipped through old issues of The Star dating back to integration. Some of us spent time on the phone with Black leaders at Texas State, past and present, asking questions to get perspective.

“Once [Texas State recognizes] us, and they attain to what we do and our culture and how we do things, then I guess the university will be more comfortable with us,” said Jaylon Douglas, an Alpha Phi Alpha member. “The fact that we’re having to push harder just to be recognized, the fact that we have to push harder just to get some type of attention…we have to do so much more than a white fraternity just because we’re Black—it shouldn’t be like that.”

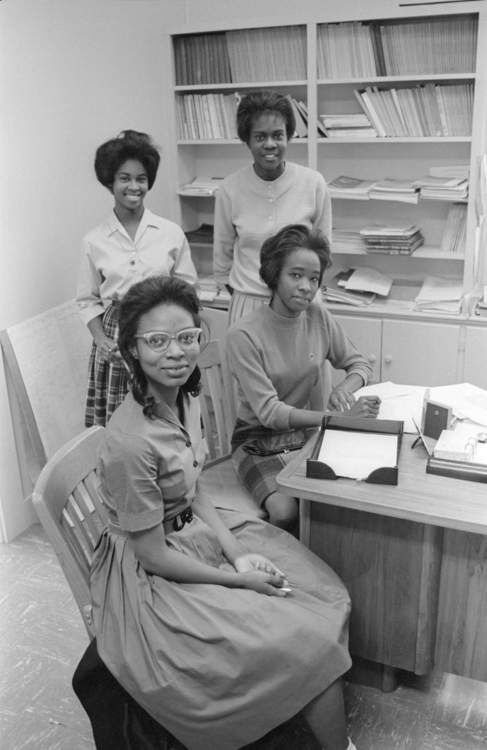

The ‘60s started it all. From the first five Black women integrating in 1963, through Johnny E. Brown becoming the first Black student-athlete, to the formation of UMOJA (meaning unity in Swahili), the first Black organization on campus, the decade was a time when Black students laid the groundwork.

The next decade marked a turning point in Black history — a series of firsts. A Black senior student ran for the San Marcos City Council. Mary Jo Crow became the first Black Texas State Strutter, a historically white dance organization. Omega Psi Phi and Delta Sigma Theta became the first Black Greek organizations on campus. The Ebony Players shifted the culture in the theater department, becoming its first Black students.

“Growing up, I was a very nerdy, quiet girl in high school, so being in theater definitely helped,” said Shanika Mendes, a member of the Ebony Players. “I never really had a group of Black friends; it was always kind of like one on one…the [Ebony Players] made me much more vocal [and helped me fall] into, ‘if I’m funny, I’m going to fully be funny’ and ‘if I’m nice, I’m going to really be nice,’ and just kind of authentically, 100% be myself.”

The ‘80s was a time of recognition and celebration. The Gospel Fest took place, which included performances from five gospel choirs and two soloists. Athletes Ingrid Phlegm, LaNell Buckley, Kelvin Moore, Darrell Hadden and Charles Austin set the bar high for SWT Athletics, shattering records and competing beyond expectations.

It was also the decade in which the university officially proclaimed February as Black Heritage Month. The crowning of Miss Juneteenth, a fashion fair produced by Ebony Magazine and a march in honor of Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday all reflected an appreciation for Black history and culture from Black students.

But the underlying issues of a lack of diversity, equity and inclusion were still present, as they have been throughout this university’s storied history. Greek Life was even more segregated than it is today. Black theater students worked their tails off just to receive half the recognition white students did. Our own newspaper missed the mark.

“Although there were many activities that took place during Black Heritage Month, I am happy to see that neither ‘our’ paper or President [Robert] Hardesty paid much attention to them,” wrote SWT student Michael Fields in a 1986 letter to The Star. “We, as Black students, must come to realize that ‘our’ newspaper and our white faculty and staff have many more important things to do other than participate in our silly celebration.”

Black students moved into the ‘90s working to create their own sense of community on campus. The Association of Black Students changed its name to Black Student Alliance in an effort to establish itself as something more than a social organization. Charles Austin continued his dominance, winning the NCAA Outdoor Championships for track and field. Martin Luther King III visited campus to speak to students. The Black-Watch was established to make African students aware of their “ancestry and greatness.”

What we now recognize as the 11% of Black students was only about 5%, and students felt it.

“I began to wonder where all of the African Americans were that I had seen at orientation and all of the socials,” SWT student Stephanie Morris wrote in the 1997 Pedagog. “I have never counted more than five African Americans in one class…I would have to work harder, know more, and perform better than any other student.”

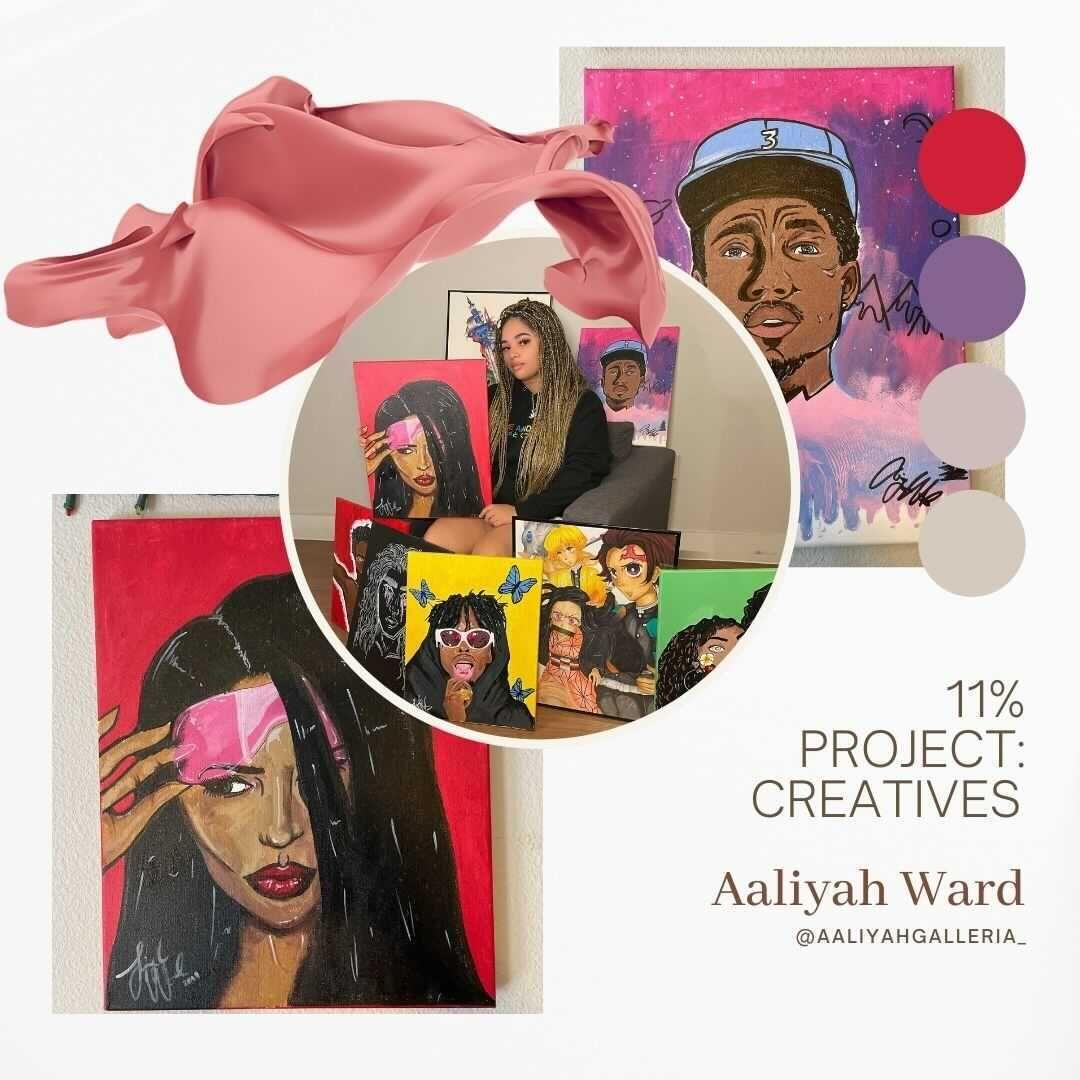

The start of the 21st century marked a Black art renaissance, or at least the Texas State version. Several student-led performances showcased the creativity and culture of the Black community. Black Men United assisted in the production of “How Far Have We Come: Thousand Miles from Nowhere”, a three-week series event that focused on correlating African culture with African American culture through music, dance and food.

Black Greek Life gave back to the community through volunteer initiatives, such as Kappa Coat Drive, led by Kappa Alpha Psi. Alpha Phi Alpha lent helping hands to victims of Hurricane Katrina at Kelly Air Force in San Antonio.

The decade also had its trials and tribulations. On the morning of Sept. 11, 2005, the University Police Department, San Marcos Police Department and Hays County Sheriff’s Department responded to an alleged report of a physical altercation near the LBJ bus circle after the African American Leadership Conference. Several students were tased and arrested.

The dispute was met with passionate responses from student activists who protested the violent police force. Students wore t-shirts with the words, “There Was No Fight,” to rebut law enforcement’s claim that it responded to the scene because of an altercation. Nearly 100 students marched from the Student Center to the Quad and circled the Fighting Stallions. The crowd eventually reached 200 students once the protest made its way to UPD, where students began to pray.

“The goal is to make sure that if there was any wrongdoing on the police officers, we would love for them to be reprimanded and also to give an official apology to Black students on this campus,” BSA President Keemon Leonard told The Star in a 2005 article.

Exploring the history of the ‘10s, it was apparent that while progress had been made, there was still long trotting ahead.

The decade embodied more firsts, such as Brittany Hunter-Lane becoming the Strutters’ first Black captain, Carrington Tatum becoming The Star’s first Black editor-in-chief, Corey Benbow becoming the first Black student body president and Ravyn Ammons becoming the Strutters’ first Black head captain.

“I need to be better; I need to be stronger,” Hunter-Lane said when speaking about her approach to the Strutters. “I don’t want to give them a question as far as whether I should be here or shouldn’t; I’m going to create space for myself while being the best.”

New student organizations also emerged on campus, including Women of G.O.L.D, the Black Art Association and the Pan-African Action Committee, an organization that helped implement the Multicultural Lounge and laid the groundwork for the African American Studies minor.

There was an uprising in student activism. Numerous Black Lives Matter protests took place throughout the community, amplifying the need for adjustments to broken systems. Black students demanded more from the university administration; students led sit-ins in the LBJ Student Center; students stood up against white supremacy and risked getting arrested in the name of equality and inclusion.

We have learned a lot about our university’s history and the efforts Black students have made to establish a home on campus. There is no “Hispanic-serving institution” or “majority-minority campus” without Black-student contributions.

Those contributions, or this timeline, do not end here. As the 11% of Black students continue to incite change on Texas State’s campus, and we continue to learn more, we will document it in hopes of educating the community around us.

Categories:

‘I need to be better; I need to be stronger’: An exploration of Black history at Texas State

November 2, 2020

Standing left to right are Georgia Faye Hoodye and Mabeleen Washington Wozniak, while seated are Dana Jean Smith and Gloria Odoms. Along with Helen Jackson (not pictured), these five women made history as the first Black students to enroll at Southwest Texas State University.

0

Donate to The University Star

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover