The current exhibitions at the Texas State Galleries, on display until Nov. 12, feature work from artists Carissa Samaniego and Maria Guzmán Capron. The works of both artists deal with issues of identity, more specifically the mixed or split cultural identities of Samaniego and Guzmán Capron.

Guzmán Capron’s “Olas Malcriadas,” loosely translated from Spanish as “naughty waves,” explores Guzmán Capron’s identity as an immigrant born in Milan, Italy to a Peruvian mother and Columbian father.

“I came to the United States when I was 17, in the middle of my junior year of high school,” Guzmán Capron said. “I didn’t speak any English, only Spanish and a little Italian too because I did live in Italy for 14 years before moving to Columbia. I have been in the United States since then, I’m still trying to figure out what that means for who I am and how do I describe myself. I figure this out sometimes through my work.”

Guzmán Capron creates what are known as soft sculptures, sculptures made of soft materials, often fabrics. The exhibit is made up of seven textile pieces, or “characters” as Guzmán Capron calls them, hung on the walls. One large figure also made of textiles lies on the floor in the center of the room.

According to Margo Handwerker, director of the Texas State Galleries, one reason Guzmán Capron was featured in the exhibit was because of how her work challenges classical notions of what sculpture really is.

“Some of them do look like paintings,” Handwerker said. “These seem so explicitly painting until you get close, and you realize they do have dimension. It’s one of the reasons the term ‘soft sculpture’ can be so much more successful in describing these types of works.”

The only piece on display that is more of a traditional sculpture is “Mar,” the large figure in the middle of the room. Guzmán Capron named the piece “Mar,” which translates to “sea,” because she wanted the piece to resemble the size and depth of the ocean.

“In some ways, the piece, the character, is kind of melting down onto the ground. I wanted it to be very flat,” Guzmán Capron said. “I had this image of this kind of piece on the floor being something that was letting go of a lot of things inside and these things would rise up to the walls and crash, almost like waves, and out of that the other characters are born.”

A unique aspect of this exhibition is the colored walls of the room. Typically, art is displayed on all white walls, sometimes referred to as “the white cube,” in order to “erase the space you are in,” according to Handwerker. In the case of “Olas Malcriadas’” the walls have been painted a variety of bold colors that both accentuate the pieces, but also give enhanced meaning to the art.

“[The white cube] tries to devoid the space of any context which is not always successful because the ‘white cube’ is itself a kind of context,” Handwerker said. “So, what [Guzmán Capron] asked us to do was to paint the space. So, on one hand, it becomes a more aesthetically pleasing and supportive environment for the works; at the same time, it also makes the overall exhibition more installation-like.”

Guzmán Capron said she has always wanted to display her work beyond the “white space” but has never had the opportunity to do so until now.

In addition to looking at her cultural background, “Olas Malcriadas” also looks to the future, both Guzmán Capron’s and everyone else’s. She said the work is a resemblance to the person she is now.

“There are so many parts of my life that are embedded in the work: Being a parent, caring, having a love for people and a love to share. I’m also looking to the future; I’m inspired by the possibilities of it. What is to come, what can we be? I like the idea that we are always changing … to appreciate all those changes, the good and the bad that we have to go through and to be excited and participate in our own futures,” Guzmán Capron said.

One room over, Samaniego’s “Coyote Ballad” explores her own split identity, growing up both in New Mexico and Minnesota, along with her family’s history and connection to the land. She does so by using objects from nature and objects that have multiple identities.

Samaniego uses the words “coyote” and “ballad” as two separate symbols that work together to describe herself and the work. To her, “coyote” represents many things. For one, “coyote” has historically been used as a derogatory term to describe someone of mixed ancestry. She uses “ballad” to refer to a form of storytelling popular in both American and Spanish traditions.

Handwerker describes the exhibit as a “concept album,” meaning one must view the pieces together to get the full meaning.

“In the way that maybe one or two songs can’t speak for the whole for the project they have to be seen in relation to one another to derive their meaning,” Handwerker said. “The meaning of this show is really tied to [Samaniego’s] self-discovery.”

Samaniego is a 15th generation New Mexican. Her family has seen New Mexico go from New Spain, to Mexico, to the U.S., first as the New Mexico Territory, and later the modern state of New Mexico.

“We have never been considered real Americans,” Samaniego said. “I grew up partially in Minnesota, a New Mexican to a Minnesotan is a total foreigner, definitely not an American. I’ve never been able to reconcile that. It’s always been present in my world and is something that continues to come up in my artwork.”

With “Coyote Ballad,” Samaniego uses an array of natural elements and objects with multiple identities to try and dissect her own identity and put it back together in a framework that makes sense to her and viewers of her work. The use of objects from nature references her family’s outdoorsy lifestyle.

The piece that perhaps does this most literally is “Conozco Coyote.” The piece consists of several coyote pelts that Samaniego has cut apart and then reassembled along with embroidery. The piece references a legend from Aztec mythology in which a woman is thrown down a mountain and breaks apart into many pieces. The woman is then reassembled, much like the coyote, and in doing so, finds power.

“There are some Chicana feminist scholars who like to use this symbol of having all your different parts when you are talking about your identity and having a mixed identity,” Samaniego said. “When you feel like you have all your different parts disassembled, the act of picking those pieces up and putting them together yourself and figuring it out is very powerful. There’s sort of this transformative process in doing so.”

The piece “Self-portrait as Hermes” was also inspired by mythology, this time Greek. The piece is made of a pair of boots with duck wings attached to them mounted on a cottonwood stump that is painted pink. The ancient Greeks believed Hermes was the messenger of the gods, communicating between the mortal world and the heavens. Due to his dealings with the mortal and the immortal, Hermes is sometimes referred to as the “God of the in-between.”

“With having a mixed identity comes the power to be able to navigate these in-between spaces because you exist in them,” Samaniego said. “You don’t belong to one place or another, but you can travel between. Coyotes can live anywhere and adapt. I thought I would make a ‘Self-portrait as Hermes’ to sort of connect myself and mixed identity to the way the in-between language has been talked about in Greek mythology.”

Being an American of Hispanic origin is a big theme throughout “Coyote Ballad.” Samaniego uses the phrase “Americaña” to describe this cross-section of her identity. In an untitled piece on display, a pink neon sign reads “Americaña” with the accent above “ñ” flickering on and off to also read “Americana.”

The piece that best represents “Americaña” is the seat of a 1985 Chevrolet El Camino decorated with embroidery titled “La Camina Caballera.” The classic car comes from America, but the name itself “El Camino” is of Spanish origin, therefore, making it “Americaña.”

Much like Samaniego, the El Camino has a mixed identity.

“An El Camino is a car and truck, it’s sort of this mixed vehicle,” Samaniego said. “The name comes from ‘El Camino Real,’ the route that the Spanish took from Mexico through what is now New Mexico. I thought that was an interesting reference to what I was already talking about. I was also born in 1985 which is why I sought out that particular year.”

Music that can be heard throughout the entire exhibit emanates from the seat. The song is by Maria McCullogh who is trained to play the violin in a variety of styles. Once again, much like Samaniego, the violin itself has a mixed identity. Depending on how the instrument is played it can be called either a violin or a fiddle.

“The fiddle is a quintessentially Americana instrument,” Samaniego said. “But it is also a quintessentially Mexican instrument when you play it with mariachi. It is also a quintessentially Celtic instrument when you play it as a violin. I thought that the fiddle or the violin is a really interesting cultural object in terms of how it operates in different settings. It’s a shapeshifter itself.”

Samaniego’s journey of self-discovery is ongoing. What is set in stone is that her family history is and will continue to be a huge influence on her work.

“A lot of my work is about having a mixed identity,” Samaniego said. “As somebody who has ancestors with 15th-century roots in what is now known as New Mexico and also German and Irish ancestors who came over in the 18th century, my own identity, being crafted from these dissimilar places of origin, is what assigns me as a ‘mixed’ person. My work is about that, it’s about understanding what that means and finding a visual language to represent that.”

“Coyote Ballad” and “Olas Malcriadas” are free to view at the Texas State Galleries located inside of the Joann Cole Mitte building until Nov. 12.

Texas State Galleries explores split identities of cultures

September 13, 2021

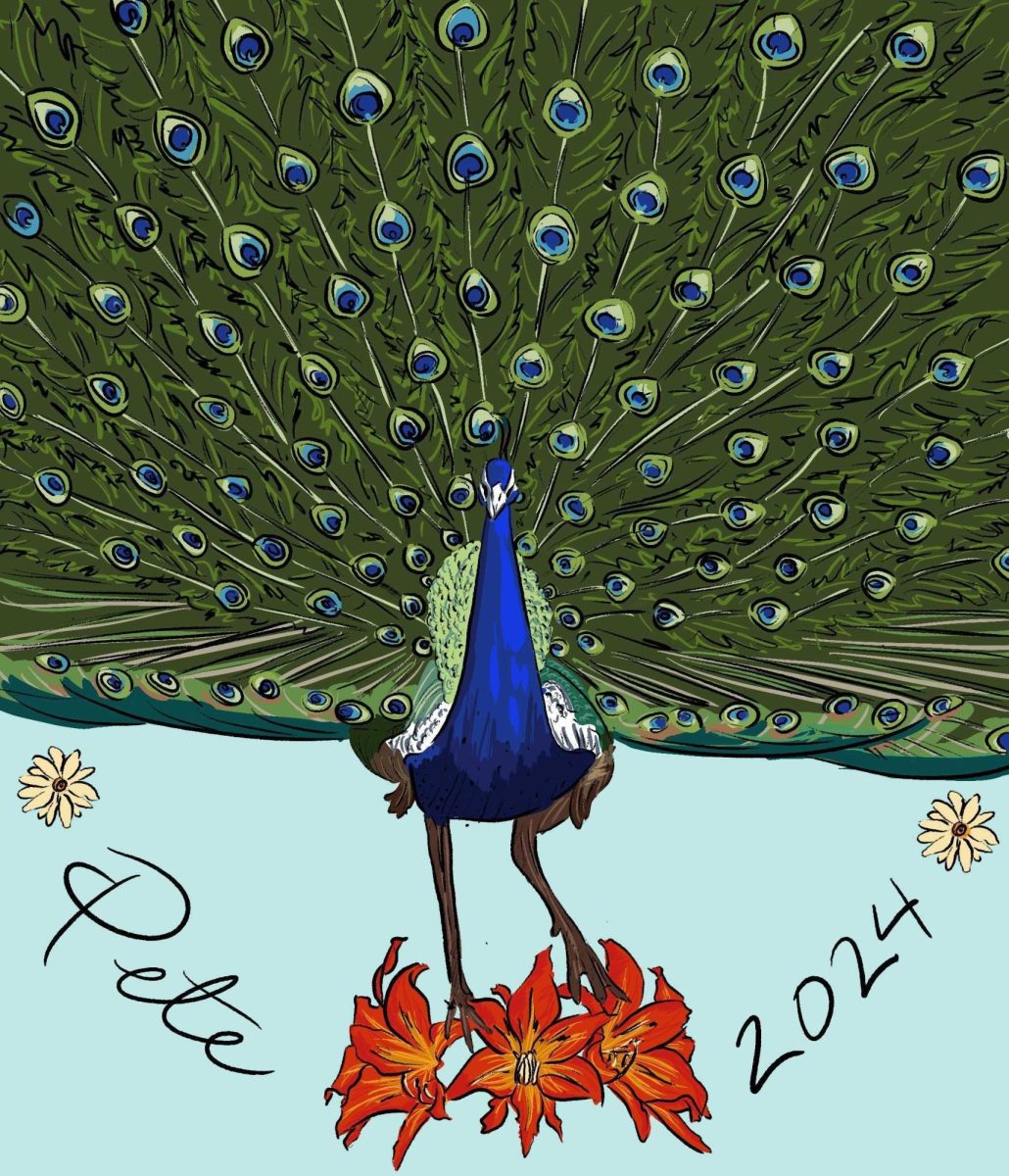

“Olas Malcriadas” by Maria Guzmán Capron on display at Texas State Galleries. The exhibit explores Guzmán Capron’s identity as an immigrant born in Milan, Italy to a Peruvian mother and Columbian father.

Donate to The University Star

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.