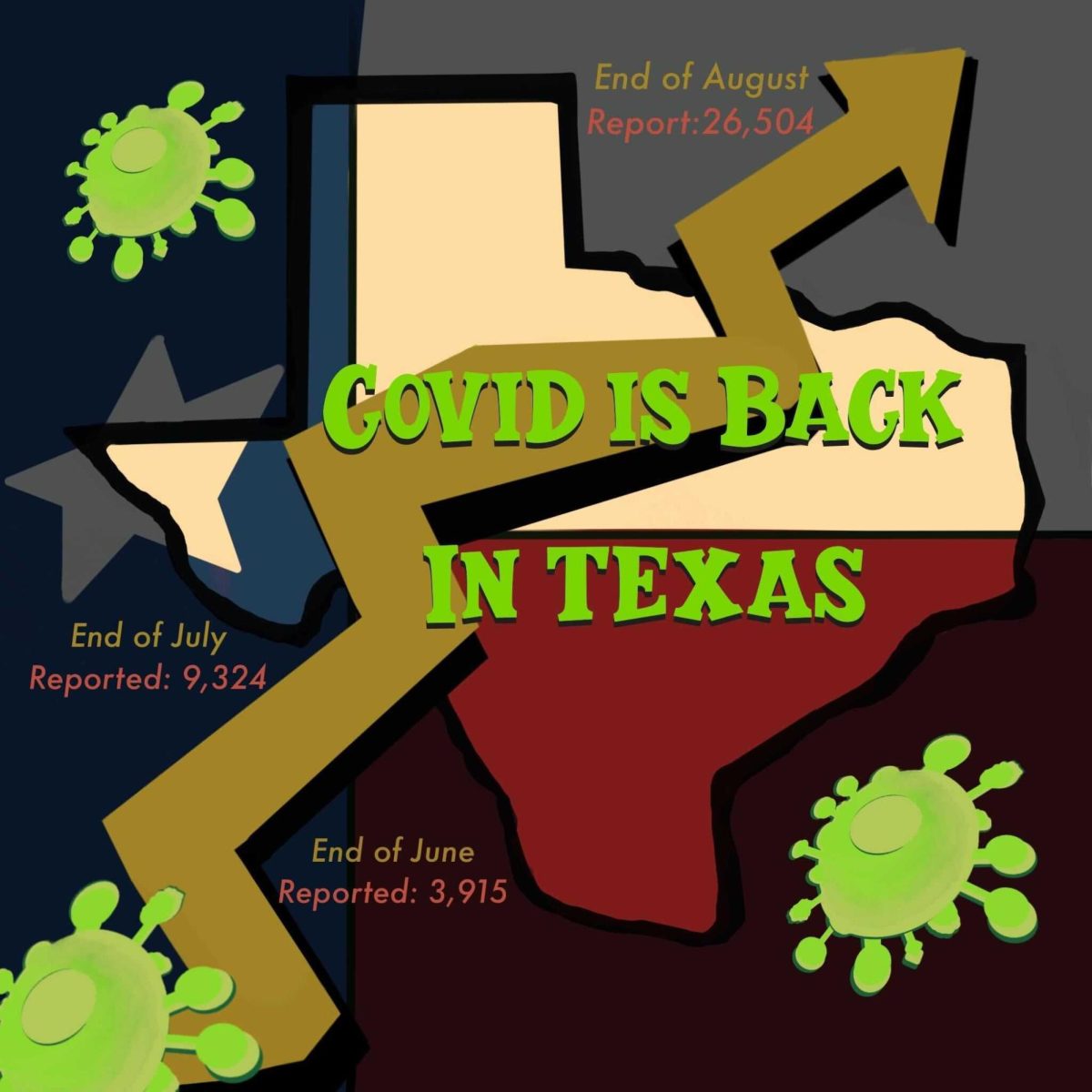

Low-income apartments in San Marcos were responsible for 30% of all apartment complex evictions filed in 2020 prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, leaving questions about what lies ahead for residents as the virus and financial uncertainty surrounding it worsens.

“I have seen what a lot of people are doing is they’re filing for bankruptcy, which temporarily can freeze an eviction,” says Thomas Just, a family law attorney in San Marcos with previous experience working with evictions. “People are doing whatever they can; it’s rough all the way around. People have lost their jobs, they’re out of money…both the tenants and the landlords are in a horrible position.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an order temporarily halting residential evictions for individuals unable to pay rent, effective between Sept. 4, 2020, and March 31, 2021, an extension of the deadline originally set for the end of 2020. The moratorium for evictions, however, did not stop all proceedings that began before.

Apartment data for early 2020 prior to the pandemic, obtained from the Hays County Justice of the Peace courts, shows the Sienna Pointe apartments, Country Oaks apartments, Encino Pointe apartments, Villas at Willow Springs apartments and Asbury Place apartments — all with some form of low-income housing — were responsible for 45 total apartment evictions filed out of 151.

“Right now, a landlord can’t really do anything…it really doesn’t make sense for any landlord to even try to do anything at this point,” Just says. “A lot of what needs to happen is — something needs to be done in terms of paying the mortgage because the landlords are hemorrhaging money they don’t have.”

Just believes once the moratorium is lifted evictions will spike, a scenario Langston Neuburger, an assistant manager who processes rent at Encino Pointe, also thinks is very likely.

“For the month of November (2020), [we only collected] 73% [of our rent],” Neuburger says. “We’re missing almost 30% of our income from the property — and that’s totally because of the pandemic…typically we’ll see collections more within the 85 to 90% range, so we’re definitely tanking as far as what our overall percent collected looks like.”

Encino Pointe is considered a tax-credit property, a property where a landlord can claim tax credits in return for renting some or all of their apartments to low-income residents at a restricted rent; tax-credit property landlords receive those credits for keeping their apartments affordable. Landlords have to ensure their prospective tenants are within a certain income restriction to qualify for a lease.

Encino Pointe rents units based on 60% and 30% of the median income of the surrounding area, resulting in tenants below the poverty line and median income of the average San Marcos family signing leases, Neuburger explains.

Neuburger says Encino Pointe has had “quite a few units” of people sitting on three-to-four months of rent they are behind on. Encino Pointe’s corporate office has allowed it to institute payment plans for people behind on rent and negatively affected by COVID-19 but, once the moratorium ends, conditions could take a turn for the worst.

“There’s going to be a lot of pressure come the end of this moratorium to start pushing evictions on those units [with people behind on months of rent],” Neuburger says. “Our corporate office is going to want us to be pushing to evict so that we can cycle those units and get people who can actually afford to stay here.”

For property managers like Neuburger, recognizing the financial burden the pandemic has placed on those struggling to make ends meet makes the human element of their jobs a lot more difficult.

For someone who outright owns a property, she, he or they has more control over her, his or their leniency toward a renter. “But when you have that faceless corporate veneer,” Neuburger explains, “it becomes a lot more difficult to institute that human element.”

“It’s tough, but we use what agency we can to try and make sure we keep people with a roof over their heads.”

During any given year, the most common reason for eviction is a failure to pay rent. To make matters worse for low-income residents, the state of Texas’ December unemployment rate stood near 7% (5.2% in Hays County) compared to 3.5% the year before. Adding more fuel to a blazing financial fire, families are still waiting on the U.S. Congress to provide more financial assistance.

Jaime Bustamantes, an assistant manager at Sienna Pointe, another tax-credit property, which is responsible for the most evictions (14) in 2020 pre-pandemic, says since the pandemic started, some residents have been struggling mightily.

“There’s people that owe quite a bit, but we are giving out resources for them to reach out to get help,” Bustamantes says. “Hays County is helping out now; there were other resources that we gave the information to our tenants for them to reach out and get the help.”

Bustamantes says he believes evictions will spike because tenants are not always utilizing the resources available to them.

“They’re not trying to find another job, or they’re just writing it [off],” Bustamantes says. “We try to talk to them [and say], ‘hey, [your balance] is going to go higher and higher if you don’t try to reach out for help. It’s going to end up bad on you because at the very end they’re going to owe the company whatever they owe.’”

“We try to help them out as much as possible; we understand what they’re going through.”

Davonte Lawson, a resident at Sienna Pointe, says getting laid off and having to find another job was among the toughest challenges that came with the pandemic. He says the apartments still accept late fees and sometimes try to keep tenants informed.

“Nobody wants to be in a bad position, but [the apartments] gotta do what they gotta do,” Lawson says. “I’ve had arguments already with these people about paperwork that I already did, but they did wrong to begin with. I just try to stay out of the way.”

Candy Hernandez, a nursing home employee who recently moved to Sienna Pointe, says the hardest day-to-day adjustment during the pandemic was to her former partner who lost his job in the food industry.

“I went to work and everything, and I was picking up shifts and paying all the bills, but he was more affected emotionally than I was,” Hernandez says.

She says the emotional fallout from the pandemic, which eventually led to domestic abuse, prompted her to move to Sienna Pointe. Despite the trial and tribulation, she says people have to keep pushing through the pandemic and make the best of their situations.

“I honestly feel like there’s nothing we can do but just keep going and doing what we gotta do every day,” Hernandez says. “You can’t just let that overcome you; you just gotta keep going. Regardless of whatever happens with these evictions…there’s nothing we can do about this pandemic.”

Eviction doubt looms for San Marcos apartments, residents struggling through pandemic

February 3, 2021

Donate to The University Star

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.