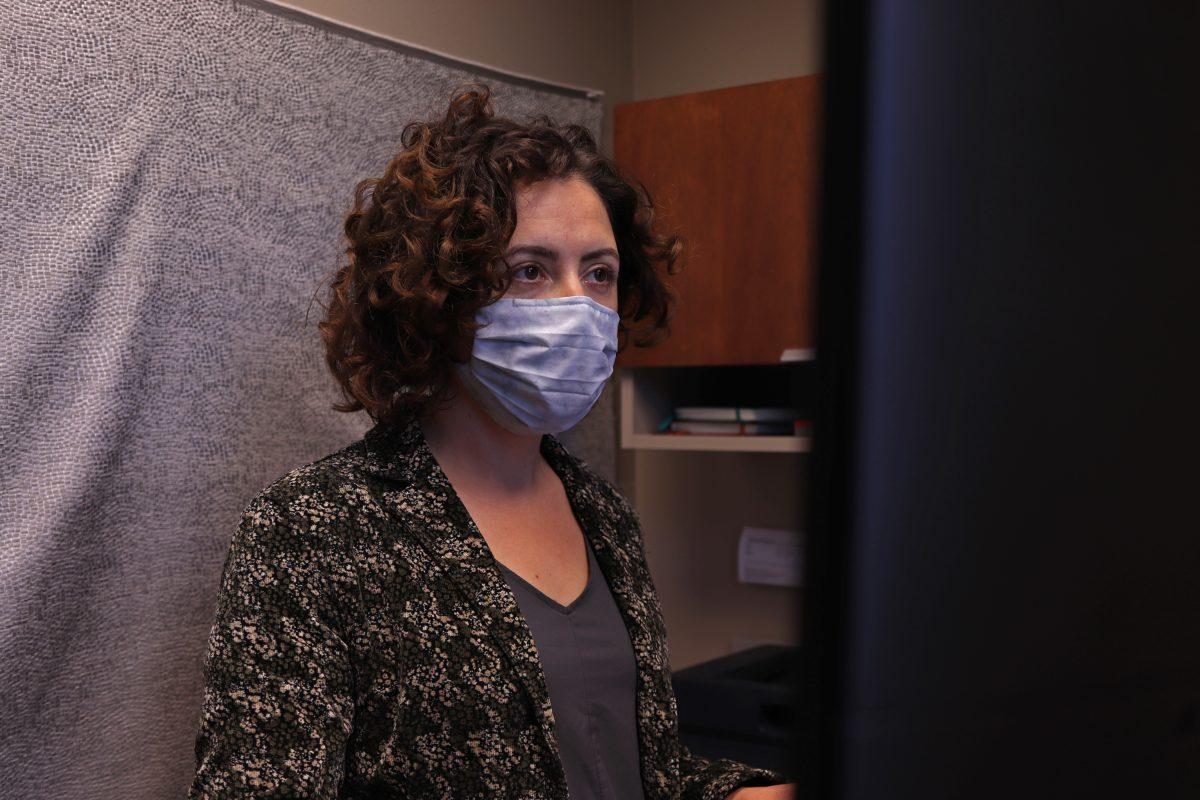

After researching food insecurity for 12 years, an assistant professor in the School of Family and Consumer Sciences is aiming to expand upon the current standards for what counts as food insecurity and how it is assessed in the U.S.

“I’ve been doing food insecurity research for a long time, since maybe 2009, and food insecurity is just a really vague term, so people don’t really understand what it is or what it means or who’s affected by it and why,” Dr. Cassandra Johnson says.

In Johnson’s recent paper titled, “The Four Domain Food Insecurity Scale (4D-FIS): Development and Evaluation of a Complementary Food Insecurity Measure”, Johnson challenges the current way food insecurity is measured, which she considers “pathologically conservative” — leaving out individuals and communities who need assistance.

“[The government is] really focused on quantitative deprivation, which is what you think of as classic food insecurity — cutting back the portion of what you eat, skipping meals, not eating for a whole day, not eating for several days, those kinds of things. It doesn’t focus on any other experiences,” Johnson says.

Johnson considers “other experiences” that current measures fail to account for are just as important as quantitative deprivation measures.

“What we know from research is that all of the experiences of food insecurity are food insecurity,” Johnson says. “We know that they all negatively affect people’s health, not just those quantitative reductions in food but the trade-offs people have to make in terms of the types they’re buying or the quality, or how they’re acquiring food, not to mention the psychological experiences with anxiety and stress.”

“All of those things matter and, right now, the measures aren’t really picking that up so that means the numbers we have are most likely an underestimate,” Johnson adds.

The original intent of conservative food insecurity measures was not to determine who would receive government assistance but rather to act as a general survey of food insecurity, Johnson says.

She says measures were designed to pick up on the most severe cases of food insecurity and were not meant to serve as the single measure used by everyone, everywhere or for every assistance application.

“A lot of times people’s experiences didn’t match up to the conversations we were having with community focus groups, and when I started doing some digging into the history of the measure, I found that it had been essentially originated from a study with a group of 32 white women from upstate New York and, to this day, most of the questions come from that study,” Johnson says. “It just proves that there’s so many opportunities to make a difference here and really promote food security in a way that will benefit people who could use a little more assistance.”

Johnson believes it is imperative that measures are broadened for the U.S. to finally provide adequate assistance to communities left behind, especially since the onset of COVID-19.

“It’s important to say that before the pandemic, food insecurity for minority households in the U.S. was already at least double what it was for white households, so then when you think that it’s doubled or tripled, it’s easy to see that this scale of food insecurity is a massive social and economic problem, not an individual problem; it’s structural,” Johnson says.

Johnson also believes the approach to understanding the various experiences with food insecurity should be more holistic than asking questions such as, ‘Did you eat something?’ or ‘Did you go a whole day without eating?’.

Mallory Best, communications coordinator for the Hays County Food Bank, also thinks more can be done to help individuals affected by the multiple aspects of food insecurity.

“I personally think that the system needs to be reworked and revisited, and I’m glad that Dr. Johnson is doing something that can help move us forward in the right direction,” Best says. “The way that the current questions determine food insecurity don’t really address a lot of the things that come along with food insecurity. There’s a lot of food-related illnesses like hypertension, obesity and diabetes among low-income populations that come about because the food that a lot of them are buying is cheaper and they don’t have access to nutrient-rich food.”

Best feels the measures should account for more than whether an individual can get their hands on food and take into account the mental and physical health implications that come with food insecurity.

“While people may be able to afford [a] consistent meal, they’re not affording [a] balanced meal which can lead to those health issues; that’s something that [the Hays County Food Bank is] really passionate about,” Best says. “And then there’s the stigma that is associated with food insecurity. If I were to guess, I’d say that the people that are answering these questions aren’t always going to be completely honest about their situation, which is a problem.”

Miriam Manboard, a human nutrition graduate student, assists with research for Bobcat Bounty, a student-run campus food pantry. Manboard says current measures for food insecurity need an upgrade.

“My current belief is that the current measurement of food security in the U.S. is not really meeting a lot of population needs,” Manboard says. “The measures miss a lot of communities. College students get left out of food assistance, undocumented people get left out and a lot of racial minorities have difficulties getting to assistance and, again, tend to get left out due to the way it’s currently measured.”

Manboard remains optimistic that researchers like Johnson will turn the tide for those suffering from food insecurity and provide a new and better way for the government to address the problem.

“It makes me very hopeful; it feels like more people are catching on to the fact that food insecurity is more than just never being able to get food and that there’s many populations that are actually food insecure that need more help than they’re getting right now, especially after this pandemic,” Manboard says. “It’s definitely a good thing for the future to think about how we can make better food assistance programs and actually start to help more people.”

Nutrition professor seeks to expand government measures for food insecurity

March 22, 2021

Dr. Cassandra Johnson uses her computer in her office, Wednesday, March 3, 2021, in the Family and Consumer Sciences building.

Donate to The University Star

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.