When the H1N1 swine flu first appeared at Texas State in March 2009, there was no widespread alarm for the virus in the U.S. It was not until April that year, when cases rose quickly around the country, that the university began to respond.

“No confirmed cases,” a university press release from May 15, 2009, said. “Two suspected cases of H1N1 flu. Both cases had a positive rapid flu test for influenza A. Confirmation of these cases is pending testing at a Department of State Health Services lab.”

The World Health Organization declared the virus a pandemic June 11 of that year. By July, Texas State had five confirmed cases of H1N1 and put out the first press release highlighting necessary precautions and safety advice.

“In an effort to prevent the spread of influenza, persons who develop a flu-like illness should stay home and avoid contact with others for seven days and until free of fever and other symptoms for at least 24 hours,” the release states.

There is no documented final count of positive cases of H1N1 at the university, but by the time the university released its last community update Oct. 30 that year, the recorded cases were in decline due to less testing, and people were reminded not to behave in such a way to cause a resurgence.

Dr. Emilio Carranco, Student Health Center director, led the university’s response to H1N1 and is currently leading efforts against the spread of COVID-19. He says both viruses were novel strains and therefore required broad responses, but each warranted its own level of alarm due to five key differences:

- COVID-19’s incubation period is between 2-15 days, while H1N1’s is 2-4 days. A potentially longer and less consistent incubation period means COVID-19 spends more time replicating before a person begins showing symptoms, effectively increasing transmission rates.

- COVID-19’s infectious period can last between 10-20 days; H1N1’s is seven days. A broader, less consistent infectious period for COVID-19—coupled with the fact that people infected may not show symptoms at all—makes it harder to slow its spread.

- COVID-19 primarily affects people over the age of 60, while 80% of H1N1’s deaths were among those below the age of 65—an irregularity among other influenza viruses.

- Though both COVID-19 and H1N1 cause “flu-like” symptoms, such as fever, sweating, coughing, sore throat, body aches and shortness of breath, COVID-19’s effects can linger and cause long-term tissue damage and heart irregularities in highly vulnerable populations. H1N1’s symptoms are typically more mild compared to those of COVID-19.

- A vaccine for H1N1 was developed in fall 2009, and medications like Oseltamivir and Zanamivir—better known as the prescription medicines Tamiflu and Relenza, respectively—were most effective in treating the virus until the vaccine was developed. Carranco says there are some medications, like various steroids, that can help critically ill COVID-19 patients, and there are efforts to develop a vaccine. As of now, there is nothing reliable and consistent that combats the virus.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, between April 12, 2009, and April 10, 2010, there were about 60.8 million cases of H1N1 in the U.S., resulting in about 274,304 hospitalizations and 12,469 deaths.

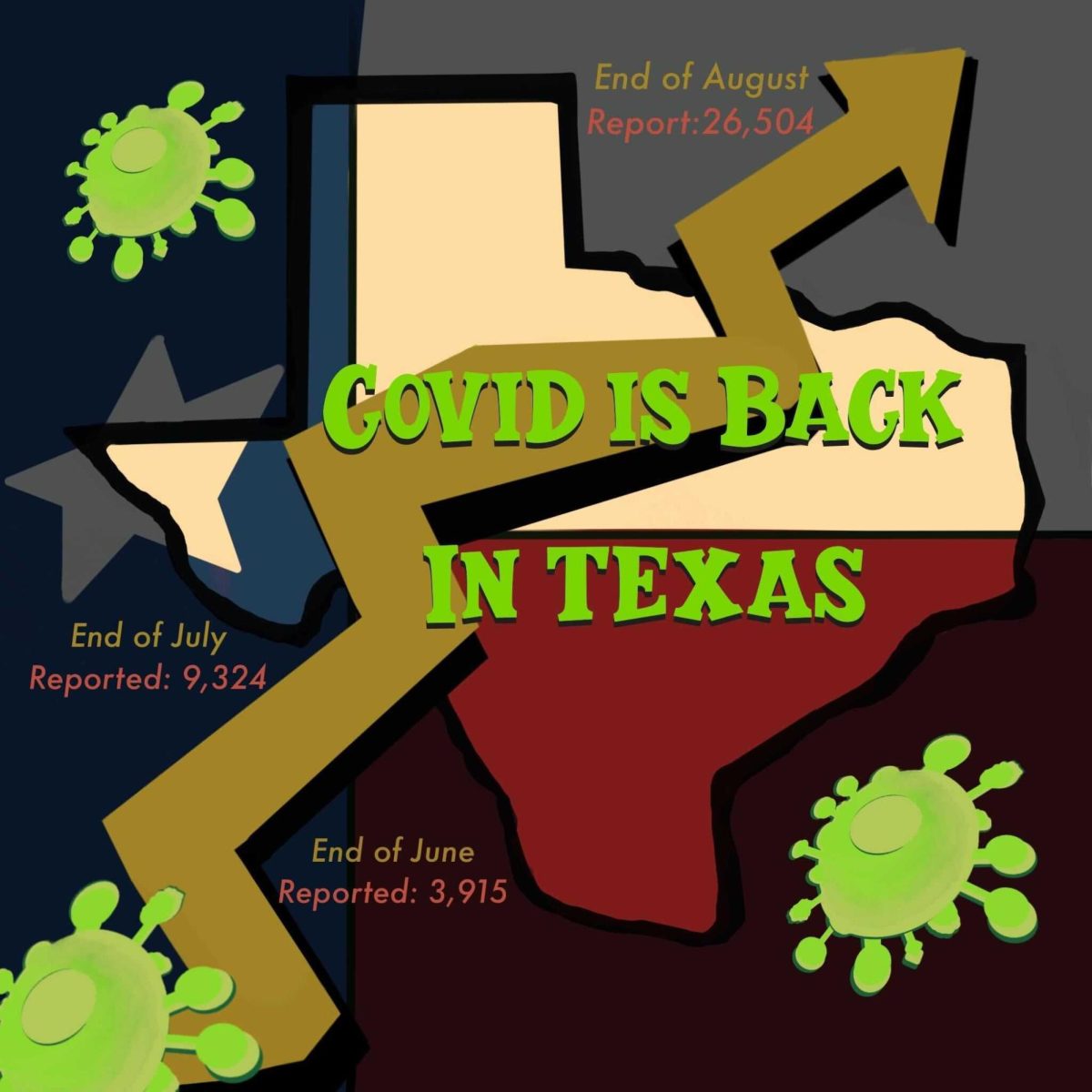

Cases for COVID-19 in the U.S. currently stand at about 7 million, while the total death count is over 200,000 and the hospitalization rate, as the pandemic persists, is 170.4 per 100,000 people, with significantly higher rates among those aged 54 and older.

In Aug. 2009, the CDC published a page on its website providing institutions of higher learning guidance for responding to and managing H1N1 scenarios at their schools.

Universities were provided informational flyers and encouraged to remind students to get their yearly flu shots, seek early treatment if they were prone to complications when infected with the flu and use respiratory etiquette, like sneezing into their elbow and appropriately washing hands.

Schools were told to separate people from infected individuals as quickly as possible and only cancel classes if infection levels became uncontrollable.

Carranco says the university did not change its operations, impose capacity limits or require masks during H1N1 because the virus did not seem as serious. He says there was testing available for it, as there is for COVID-19, but testing for the flu eventually became pointless as almost everyone coming into the Student Health Center with “flu-like symptoms” was able to stay home for a week and return to classes.

“Initially, there was a lot of concern about how serious H1N1 was going to be. As the months went by, we realized that H1N1 was primarily going to cause mild symptoms,” Carranco said.

Allie Watters, a Student Government senator during the 2009 pandemic, says she remembers hearing about isolated cases and small outbreaks around campus, but H1N1 was largely perceived as a “foreign virus” by students—something that did not affect their daily lives and routines.

“I don’t remember being concerned about it. I definitely don’t remember anyone wearing a mask,” Watters said.

English professor Steve Wilson has been teaching at Texas State since 1987. He says H1N1 did not change any of the daily functions of the university.

“Students and professors did not take H1N1 as seriously as they probably should have, looking back,” Wilson said. “H1N1 didn’t last as long [as COVID-19]—for one thing. People just didn’t come to class, or [they] stayed home if they were sick. We didn’t isolate people; we didn’t do any of those things. I guess what that means is, we got lucky.”

Carranco says the university developed and wrote a pandemic response plan for H1N1 largely inspired by the CDC’s recommendations at the time, which set the framework for COVID-19’s Roadmap to Return.

He says higher transmission rates, like those demonstrated by COVID-19, come with the need for methodical testing, more intense social-distancing, contact-tracing, quarantining, isolation and distance learning, but the defining challenge in dealing with COVID-19 is a political atmosphere which encourages divisiveness and the spread of misinformation.

“I am very concerned that people don’t trust,” Carranco said. “They don’t trust public health; they don’t trust the government; they don’t trust what scientists are saying, so we’re not getting a uniform response. The country as a whole is not responding.”

San Marcos City Council Place 1 Representative Maxfield Baker was a Student Government senator in 2009. He says the local response to COVID-19 is complicated by the over politicization of health guidelines and disregard for science, a challenge unique to this pandemic.

“For H1N1 there was a consistent message from the top down. It didn’t seem like there was a lot of bickering about the science,” Baker said. “To hear some of my colleagues and mayors in other towns questioning the science on [COVID-19] is just, you know, baffling.”

Carranco says Texas State sees public health as a priority on large college campuses and, as COVID-19 continues to spread while approaching the annual flu season, the university is remodeling a portion of the Student Health Center.

Future changes and additions may include negative pressure rooms, increasing the number of staff trained in contact-tracing to up to 12 people, moving students within student housing around to allow for more quarantine and isolation spaces, purchasing more personal protective equipment and expanding telehealth services.

“We’re trying to prepare for the increase in demand of services and supplies, either because COVID-19 has worsened, or because the annual flu is now on the scene,” Carranco said.

Carranco says the developments in the student health services and equipment are mostly new and a direct result of having to respond to COVID-19, but they are not only effective in treating one virus—they will help the university combat any pandemics in the future.