Keely Reynolds has worked with and encountered every kind of child: the gifted, gangster, abused; kids with happily married parents to kids living with no parents. She taught at Lockhart High School for 11 years before realizing she was doing more counseling than teaching, prompting her to attend Texas State to get a master’s in counseling. She found adolescents with no foundation at home—ones considered “at-risk”—she enjoyed working with the most.

This desire led Reynolds to Pegasus. When she was hired as a school counselor in 2012, students were being educated by The University of Texas charter school. At the same time, Robert Ellis was in talks with Trinity Charter in hopes of moving to its services, as the UT system took an umbrella approach in teaching the boys. According to Reynolds, catering to each campus the same way was not beneficial to the Pegasus kids and thus, Trinity became the official charter school on Pegasus grounds.

Trinity is an accredited charter school under the Texas Education Agency and specializes in educating kids in residential treatment facilities. It encompasses 12 campuses with 430 students in total. Once boys struggling with behavioral problems get removed from public school, this is where they go.

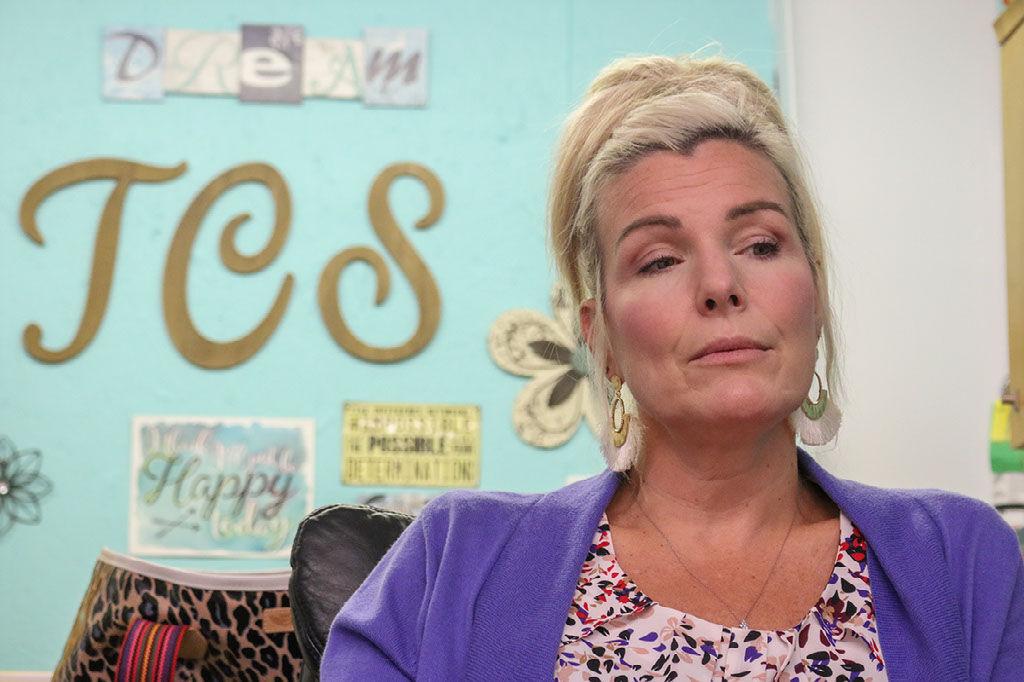

Reynolds now serves as the principal of the charter school and has her LPC, which she stressed has come in handy more times than not.

Pegasus and Trinity, while separate entities, work hand-in-hand to deal with poor behavior problems. Pegasus staff sits in classrooms with the teachers if behavior gets out of control or a boy needs to leave class due to extenuating circumstances.

Kevin Smith is the coordinator of transition services at the Trinity-Pegasus campus and works closely with Reynolds to help kids adjust to the school. He said teamwork between the facility side and educational sector keeps day-to-day routines running smoothly.

“We talk as a team about a problematic kid then go together to meet with him,” Smith said. “Information is pretty powerful out here. If a kid just found out they’re not going home, their mother gave them up or a family member went to prison, that’s pretty impactful news. If a kid is shut down in a classroom, education is the last thing on their mind. By being informed about that, we can spread that news and give him a pass for the day.”

By informing teachers and staff about what may be going on with the inner workings of a student, Smith said this creates the best dynamic in the classroom, behaviorally. True fist-fights rarely occur, as physical altercations get broken up immediately. Smith and Reynolds only get involved in classroom problems if troublesome behavior is continual.

“I’ll have to take my principal hat off and talk to the boys about what is really going on and why they’re not behaving in class,” Reynolds said. “This is helpful because talking to the principal normally correlates to consequences. I want to provide as many positive experiences as possible. Starting day one, we let them know we are a very positive-energy environment.”

No negative attitudes are allowed, Reynolds said, as she showed off her unicorn collection amidst the leopard-print, pastel backdrop of her office. If her words fail to get through to students, her space might do the trick.

“These kids have just been constantly torn down; they come from abuse and trauma and need to experience success,” Reynolds said. “We want them to leave here saying, ‘I’m good at math, science and I want to get my high school diploma.’ While they’re here, they know they’re going to receive positivity and get celebrated for everything good they do.”

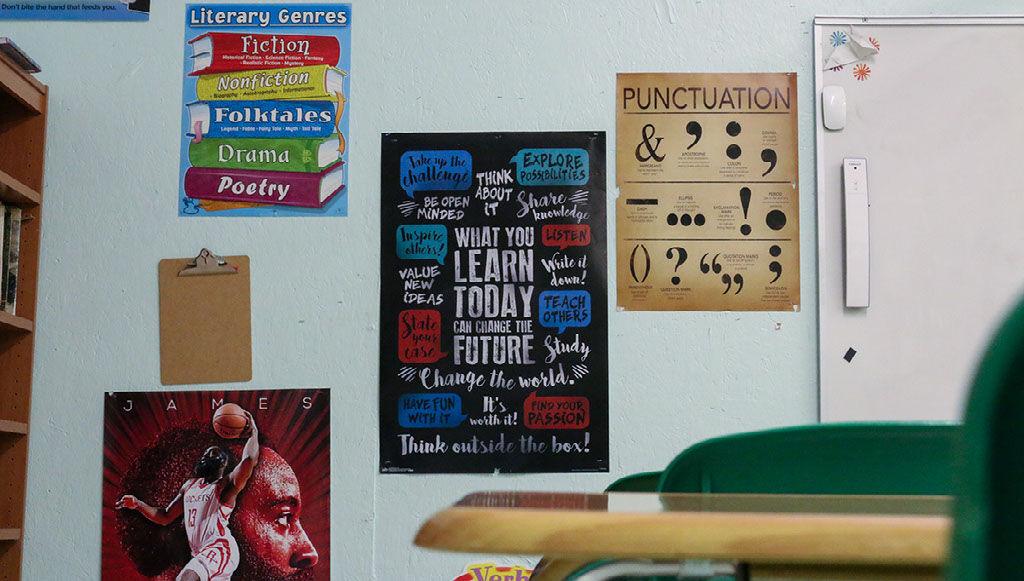

Pegasus boys are mandated to attend school just like any other child their age. Students take the STAAR test, are provided curriculum and receive grades. Even the school start time and class schedule throughout the day is the exact same so once boys successfully complete the program, their adjustment back into “normal” school is a smooth one.

“We are a real school, and kids will leave with a transcript and report card,” Reynolds said. “The things boys do and learn here gets transferred easily to wherever they go next.”

The school administration implements a restorative discipline approach—no detention or punitive action—as the boys are thought to be punished enough having to be away from what is familiar.

Each boy follows an individualized learning plan. Within 10 days of enrollment, students are given a diagnostic test in math and reading so they may learn—for the first time—on the right level. While one child may technically be a ninth-grader, they could test at a fifth-grade math level or third-grade reading level. According to administration, most students going through Trinity charters have about a two-year gap in their education from being in and out of school so often.

“Some parents will pull them out and ‘homeschool’ them, which doesn’t help; they just want to keep them out of trouble,” Reynolds said.

The majority of the kids Reynolds and her team see should have been identified as special education or 504, meaning a student must be determined to have a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more major life activities. Since the boys are, more often than not, unable to hold down one school for long, they have not been coded for special services. Trinity provides necessary resources so boys can be protected and acquire services they need to learn successfully.

Smith said boys with behavioral problems, on average, have been in government or placement agencies since they were six or seven years old. He understands the impact constant instability may have on youth; he emphasized—darkly—kids know how to play this game. However, in more ways than not, Pegasus is the best place a lot of the boys at the facility have ever been.

“

These boys can sleep safely; they’re getting three meals and a snack daily. They have positive things to do. It’s not a lockdown environment and no one is going to hurt them.”

— Kevin Smith

Robert Ellis still has nightmares from his youth, and his memories of abuse will never go away. However, he believes everyone has their own issues demanding to be addressed and he deals with his every day.

“I wouldn’t have survived without His hand on me,” Ellis said. “God was with me the whole way and helped lead me in the right direction. I can not only sympathize but empathize with these boys. I’ve been through the gamut.”

Ellis wants only one sentence written on his tombstone once his time comes: God helped him, and he tried to help others.

The Pegasus School is not religiously affiliated.