After nearly a year of devastation brought forth by the COVID-19 pandemic and recent news of Texas becoming the first state to administer 1 million doses of vaccines, Texas State’s Student Health Center is gearing up for its own vaccination efforts with hopes the campus community will take advantage.

Texas State, an approved vaccine provider, created a workgroup during the fall semester to begin planning for distribution and now expects to receive either the Food and Drug Administration-approved Pfizer or Moderna vaccines in the coming weeks.

“We’ve seen those horrible pictures of people standing in line for hours and hours to get the vaccine; that is not how we’re going to distribute vaccines on our campus,” says Dr. Emilio Carranco, the Student Health Center director. “The Department of State Health Services is going to tell us which priority groups we are to administer the vaccine.”

Carranco suspects the state health department will want to send the Pfizer vaccine but says it is possible Texas State could receive both, “a more difficult logistical challenge” the university can manage if needed.

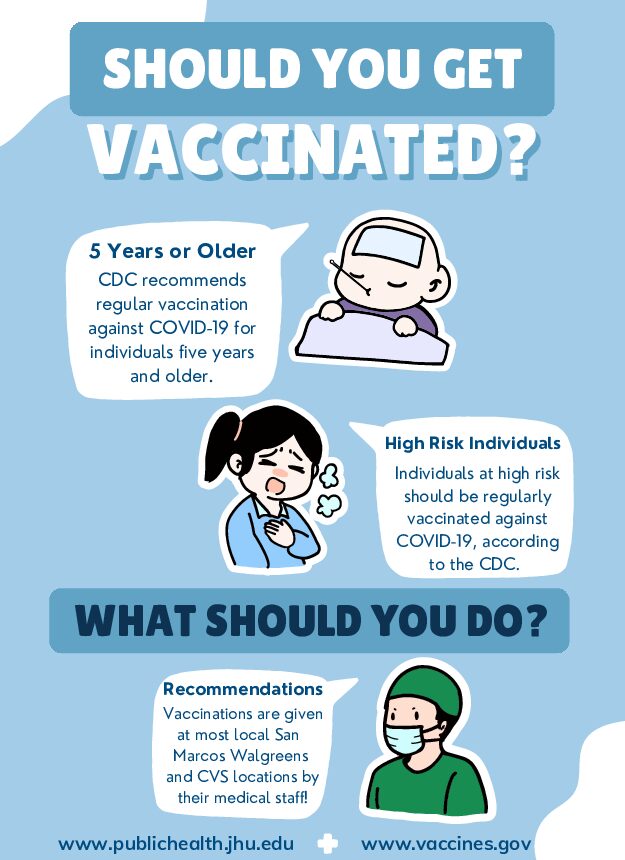

Both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines require two doses (both doses must be the same brand), with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention not recommending the latter dose be taken earlier than three weeks (Pfizer) or one month (Moderna). Once the university has access to the vaccine and knows the priority groups, Carranco says it plans to reach out to members of the university community to receive their shots.

When people sign up for the vaccine, they will schedule both their first and second shots, respectively.

“We will notify them that we have a vaccine available; we will provide a link that they will be able to use to register for the vaccination; they will register in time slots,” Carranco says. “What I expect is we’re going to get multiple allocations. And the first allocations might just be a few hundred doses of vaccine, and then I see that becoming a few thousand. And then I see that becoming several thousand.”

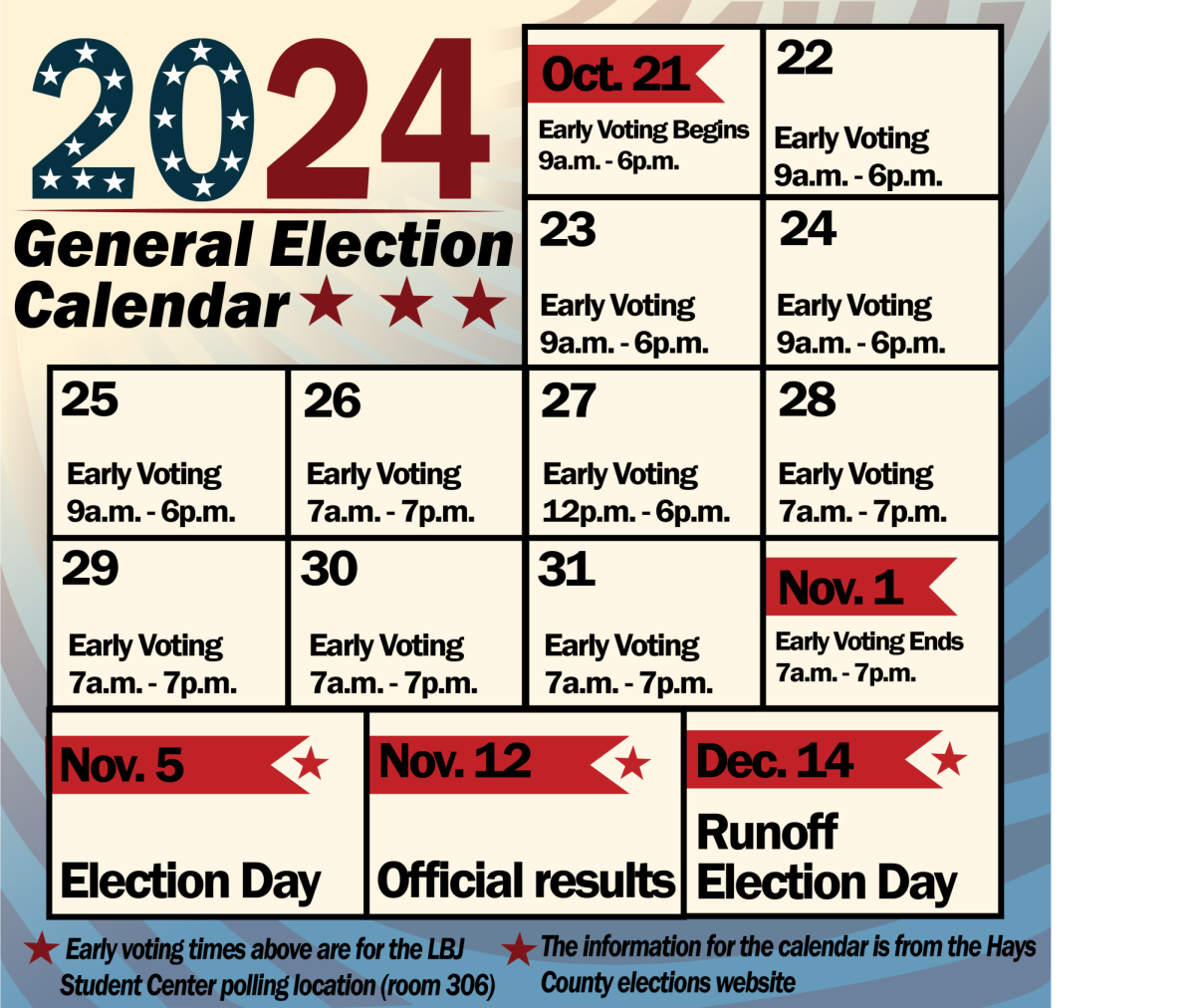

To accommodate a potentially large number of high-risk people who will seek a vaccination, Texas State plans to utilize the ballrooms located in the LBJ Student Center as its mass vaccination site, citing the need for a week-to-week space large enough to sign people in and allow them to “stay for at least 15 minutes and in some cases, 30 minutes,” Carranco adds, while adhering to social distancing protocols.

When Texas State begins its efforts, it will find itself in a position where it has an abundance of resources — a luxury Hays County does not currently benefit from.

“Our role in the county has been to take care of Texas State,” Carranco says. “So when we draw up county emergency management plans, the expectation is that Texas State will take care of itself; we are half the population of San Marcos [which allows the county to concentrate on the other half]. So if we can take care of ourselves, that’s saying a lot.”

“Now, we still need help; we still need help from our county partners. But we have the resources to do this.”

But Texas State’s resources alone will not be enough to overcome the misinformation spread about vaccines — whether through social media or word-of-mouth — which has raised skepticism throughout the country about whether it is safe to get vaccinated.

“What’s really happened is that we were able to use tools that weren’t available to us a decade ago, to be able to create and test vaccines much faster than we ever could,” Carranco says. “That should be a positive. But for some reason, people saw that as a negative and started to wonder whether corners were cut. No corners were cut; we just have better tools available to us to be able to create and test the vaccines.”

Still, Carranco and other university and state officials’ efforts to communicate the safety of the vaccine, part of which will be their willingness to get vaccinated themselves, will likely come with additional challenges.

Texas State’s student population is 40% Hispanic and 11% Black, and communities of color have a history of unequal healthcare treatment compared to their racial counterparts.

COVID-19 has killed communities of color at a disproportionate rate. Black women are two-to-three times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications compared to white women. The Tuskegee Study, a decades-long syphilis fiasco that involved hundreds of Black men, still resides in the consciousness of communities negatively impacted by the healthcare system.

Some feelings of skepticism toward healthcare treatment — including the development of effective COVID-19 vaccines — are rooted in the history of malfeasance toward marginalized groups.

In response to misinformation and fear surrounding the vaccines, Carranco says the university is trying to make the case that vaccinations are what will end the pandemic.

“If we can get enough people vaccinated, then the ability of this virus to be able to move from person to person will start to diminish,” Carranco says. “Herd-immunity people debate whether that’s 70% or 80%, or 85%. But the fact of the matter is, the more people who are vaccinated and now have developed antibodies to this virus, then the less likely people will be able to easily pass it from one person to the next to the next.”

Jamie Thomas, a psychology sophomore who serves as the event coordinator for Black Women United, says when the organization had discussions about COVID-19 and the vaccine before it was made available on a national scale, some members expressed reluctance to take it. She says the disproportionate impact healthcare has on Black women takes a mental toll on her and others.

“We want to be able to trust our medical officials and people that have authority over us — that are supposed to keep us safe. But in the past, they haven’t been doing their job when it comes to us,” Thomas says. “It’s hard to want to put your trust into people that have let you down before.”

Despite those feelings, Thomas believes she and other members of the organization will eventually trust the vaccine, adding she respects health officials like Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and personally has family members in the medical field.

“We can read any information we need to and see for ourselves in the news if this vaccine is going to work,” Thomas says. “So I think it really is something that most of us are going to be willing to get.”

Others, such as Reece Jordan, an agricultural business and management senior, have not had to experience the same mental dilemma Thomas described but still would like to see how people react to the vaccines. He says he will have to spend more time educating himself before taking one.

“I do know it could be beneficial but, also, not knowing much about it, you kind of want to see side effects and what research has gone into it,” Jordan says. “And so [if] the vaccine can continue to show positive results…we can get rid of it. So if that’s the case, then I think everybody should get it.”

Categories:

Texas State prepares for COVID-19 vaccine distribution

Jaden Edison, Editor-in-Chief

January 18, 2021

A view of the LBJ Student Center from outside the building’s ballroom, which will serve as Texas State’s mass vaccination site.

0

Donate to The University Star

Your donation will support the student journalists of Texas State University. Your contribution will allow us to purchase equipment and cover our annual website hosting costs.

More to Discover